In Taiwan’s foothills, suspension bridges — or the remnants of them — are almost as commonplace as temples.

“Suspension bridge” is a direct translation of the Chinese-language term (吊橋, diaoqiao), but it’s a little misleading. These spans aren’t huge pieces of infrastructure. The larger ones are just wide enough for the little trucks used by farmers. Others are suitable for two-wheelers and wheelbarrows. If one end is higher than the other, they may incorporate steps, like the recently-inaugurated, pedestrians-only Shuanglong Rainbow Suspension Bridge (雙龍七彩吊橋) in Nantou County.

Because torrential rains hammer Taiwan during the hot season, the landscape is scarred by ravines and wadis. Fording certain creeks is out of the question. After World War II, bridges made of steel wires and wooden planks, held in place by a concrete tower on either side, made it possible for remote hill farmers to get their crops to market, and for their children to attend school.

Photo: Steven Crook

In the past few decades, many suspension bridges have been superseded by bigger structures able to carry two-way traffic. Several old bridges have been left to collapse, like one beside Taichung Local Road 100 in Taiping District (太平). In a tropical climate, the wooden elements quickly rot. The hawsers anchored to each side are more durable, but may snap if struck by falling rocks (a significant threat in mountainous areas) or stretched because one of the towers has toppled.

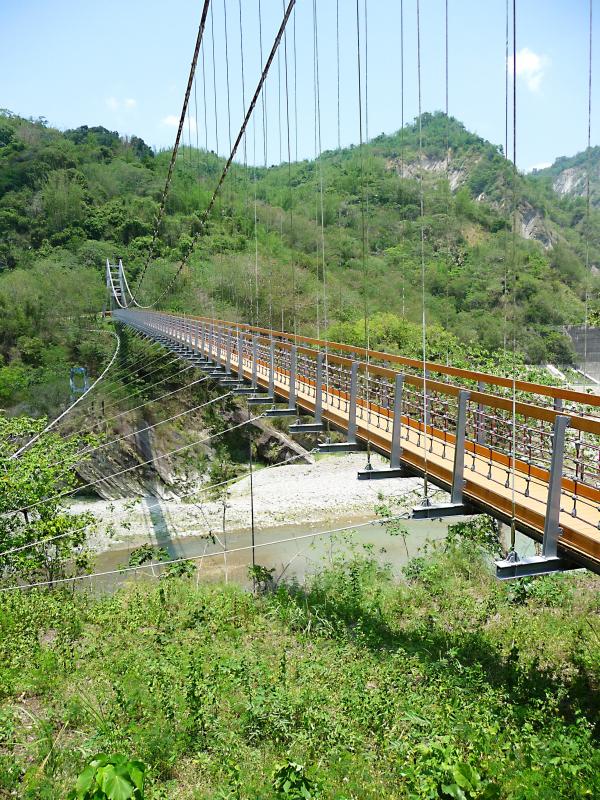

Others are properly maintained or replaced, and have become tourist attractions. When I reached the northern end of Provincial Highway 21, after the most challenging section of one of the most difficult bike rides I’ve ever done, I spent a good bit of time on Fusing Suspension Bridge (福興吊橋), taking in the scenery and catching my breath before returning to the road.

The 150m-long bridge crosses the Dajia River (大甲溪), which here divides Taichung’s Sinshe (新社) and Dongshih (東勢) districts. Its current form dates from 2013; previous editions were of great importance to those living nearby, as there was no road bridge here until 1971.

Photo: Hsieh Chieh-yu

I’ve not had a chance to visit Shuanglong Rainbow Suspension Bridge (雙龍七彩吊橋), but back in 2015 I did get to see the original bridge. The older structure — which remains in place, parallel to the new one — wasn’t built so people could cross the valley, but to support and maintain a pipe which carries water to the nearby indigenous village.

At the time of my visit, signs informed outsiders that anyone making an unauthorized crossing of the pipe-bridge would have to pay a fine. In the hour or two I spent there with friends, at least four people ignored the warning and went all the way across to get a closer look at Shuanglong Waterfall (雙龍瀑布). I didn’t, and not simply because it was prohibited. It looked terrifying.

Back in the late 1990s, a suspension bridge in the mountains caused me a moment of horror, and I wasn’t even on it. Camping alone without a tent in what’s now Kaohsiung’s Taoyuan District (桃源), I’d settled down for the night beside a tiny stream, not really noticing the bridge almost directly above me.

Photo: Steven Crook

Sometime later, echoing thuds wrenched me from deep sleep and out of my sleeping bag. When my head cleared, I realized a truck had clattered at speed across the bridge. My brain, interpreting the noise as a rockslide, had pushed the panic button.

More recently, I’ve ridden my bike across what’s said to be the longest steel-cable footbridge in Taiwan.

The 360m-long Shuangshih Suspension Bridge (雙十吊橋) crosses the Wu River (烏溪) in Nantou County’s Caotun Township (草屯鎮). A relief image on the river’s north bank celebrates the life and works of Lin Chi-mu (林枝木, 1930-2003), the engineer who oversaw its construction in 1977.

Photo: Steven Crook

Lin began his bridge-building career at the age of 18, and played a role in the building of over 150 bridges throughout Taiwan, among them: Baling Suspension Bridge (巴陵吊橋) beside Highway 7 in Taoyuan; Wulai Suspension Bridge (烏來吊橋) in New Taipei City; and the original version of Pudu Bridge (普渡橋) at Tiansiang (天祥) in Taroko National Park.

In an interview he gave shortly before his death, Lin said that the cost of building a 150m-long suspension bridge is about one tenth of that of a concrete bridge of similar length, and the former can often be completed in less than four months.

When working in remote locations, he usually slept and cooked on-site, sometimes accompanied by his wife. Getting the first rope across the defile was often difficult and dangerous; one man would have to climb down, then swim across. Once a zip line had been set up, workers and materials could be sent over. During his career, Lin lost three teammates to accidents.

Several of Taiwan’s steel-cable footbridges enhance the scenery in which they’ve been set. Neiyechi Suspension Bridge (內葉翅吊橋) is in this category, even if it’s hard to reach.

The bridge crosses the Zengwen River (曾文溪) where it flows out of Alishan Township (阿里山鄉) and into Dapu Township (大埔鄉). And, in my opinion, the bilingual sign pointing to it at intersection of Provincial Highway 3 and Chiayi Local Road 133 borders on the irresponsible. City slickers who try to drive to it will at best struggle on this rough and narrow road, and at worst damage their vehicles.

It’s 2.3km from Highway 3 to the southern end of the 164m-long bridge. Looking down as I pushed my motorcycle across, I could see fragments of an earlier bridge destroyed by Typhoon Morakot in 2009.

The northern end is much closer to a decent road, but I didn’t enjoy riding up the twisting track. It was steep, and much of the surface was rutted or shattered.

After Morakot, the government spent NT$47 million to rebuild Neiyechi Suspension Bridge. Last year, a budget of NT$15 million was approved to reinforce the bridge, strengthen the side fencing, and replace the planking with plasticized wood. It seems the authorities have lots of money for a bridge that no one actually needs, but not enough to improve the roads that lead to it. Do they want tourists to enjoy it or not?

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, and author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide, the third edition of which has just been published.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with