Ever since I stepped foot in Zhishan Garden (至善園) when I first arrived in Taiwan, I have been intrigued and comforted by the scenery of traditional Chinese gardens. These walled pockets of green are found in many cities around the world including Sydney, Berlin, Beijing, Zurich and New York.

Taiwan has a fair share of these havens of tranquility, with the following three found in Taipei and New Taipei City.

ZHISHAN GARDEN

Photo: Jaya Asmi

During that maiden visit to this garden tucked in the front corner of the National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院), I was bewildered by the rather strange layout of the place. The purpose, structure and details of Chinese gardens seemed conspicuously different from their Western counterparts: I saw ancient trees instead of manicured lawns and symmetrical flower beds, natural-looking bodies of water instead of elaborate fountains, and zigzagging pathways leading to elegant pagodas rather than geometrically-placed paved paths.

The naturalistic style may give the idea of a Chinese garden being unkempt but I later learned that the opposite is true: every aspect of a traditional Chinese Garden is carefully planned. The 3,500-year-old art of Chinese landscaping embodies the philosophy of yin and yang, and presents the four principles of water, rocks, plants and buildings in a harmonious balance. A visit to these oases takes you to an ancient and magical world of symbolism and metaphors.

Named the “Garden of Perfected Benevolence,” the Zhishan Garden mimics the traditional garden styles of the Ming and Song dynasties. Upon entering the enclosed space through the lion-guarded front gate, you are greeted by a brook nestled under palm and bamboo groves. As you continue walking, the path yawns into an open space occupied by the Brush Washing Pond (洗筆池) flanked by paths on either side. The left side hosts a picnic area and a meandering trail which leads to the two-story Pine Wind Pavilion (松風閣).

Photo courtesy of Manoj Kripalani

As you walk on the trail, you will see an arched bridge which connects the Brush Washing Pond to the Dragon Pond (龍池), aptly named because of the stone dragon spouting water in the middle. Almost every Chinese garden has such bridges symbolic of the moon. They are considered complete in themselves without any need for a balancing element as their reflections in water give the impression of a full circle.

After admiring the plethora of koi fish, turtles, geese, ducks, swans and doves inhabiting the ponds and their rockeries on the walk, I proceed to the second floor of the Pine Wind Pavilion and appreciate sweeping views of the garden.

If you stay long enough at the pavilion, you might understand why Chinese scholars saw gardens as retreats in nature where they could seek inspiration. You might even be accompanied by an old violin-player like I was during one of my visits. I suspect that even among the busy foliage, chirping birds, gurgling water, giggling children and enthusiastic Instagrammers, you will find a stillness within you.

Photo courtesy of Manoj Kripalani

Walking back along the winding canal and the zigzag pathway to the West Bridge Pavilion (碧橋西水榭), there are many plants cultured for their symbolic meanings — bamboo for its strong and resilient character, banana for the pleasing sound of wind and rain on its leaves and pine for its tenacity.

Zhishan Garden is located at the National Palace Museum (國立故宮博物院), 221 Zhishan Rd Sec 2, Taipei City (台北市至善路二段221號) and is open daily from 8:30am to 6:30pm. It is closed on Monday. Admission is free.

LIN FAMILY MANSION AND GARDEN

Photo: Jaya Asmi

In my quest to understand and enjoy other traditional Chinese gardens, I visited the almost 200-year-old Lin Family Mansion and Garden (林本源園邸) in New Taipei City’s Banciao District (板橋) soon after.

Once the home of many generations of the wealthy Lin family, the place is now a tranquil retreat to relive history and enjoy solitude. Though the actual mansion is off limits, the NT$80 entrance fee will afford you hours of entertainment exploring the surrounding Chinese garden.

Among its many resounding features, the Lin Mansion Garden’s eight big and small buildings are the most striking. Dotted among various bodies of water, you will find the Jigu library (汲古書屋) constructed for the junior Lins’ academic pursuits, Lai-Ching Hall (來青閣) for entertaining guests and Shangyu Yi (香玉簃) for admiring plants.

Photo: Jaya Asmi

No Chinese garden is complete without calligraphy, and there are numerous four character inscriptions and moral teachings inscribed in these halls and pavilions.

A vital element of a Chinese Garden is jiejing (借景, “borrowed scenery”). The garden is not a vast expanse that the viewer sees in one sweeping glance; rather it is taken in as a series of frames skillfully created using walls, bridges, walkways, windows and natural barriers. This technique gives the illusion of infinite space within an enclosed area.

The lattice windows and decorative openings in the walls of the pavilions in the Lin Garden visually link different places; one can see the same object from different vantage points but still feel that they are looking at something new.

Photo: Jaya Asmi

The Lin Family Mansion and Garden is located at 9 Simen St, Banciao District, New Taipei City (新北市板橋區西門街9號). Open daily from 9am to 5pm. Admission: NT$80

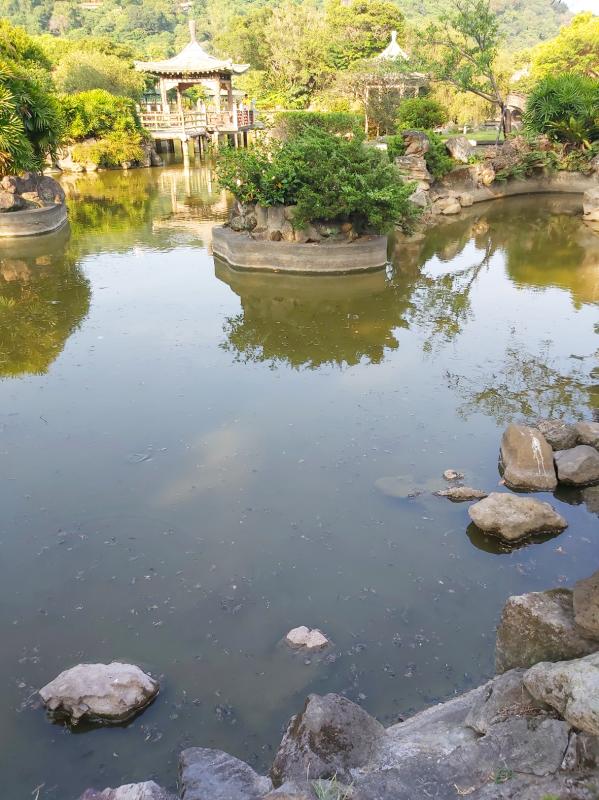

SHUANGXI PARK AND CHINESE GARDEN

After having visited several of these natural-looking but man-made retreats, if I had to pick a favorite Chinese garden in Taipei, it would be the Shuangxi Park (雙溪公園) in Shilin. With beautiful rockeries, zigzagging pathways, caves, ponds, a thundering waterfall and a beautiful moon bridge, this very accessible garden packs a lot of punch in a small area.

Rocks are to a Chinese garden what sculpture is to European ones, and the Shuangxi Park is dotted with the most remarkable rocks. Some, like the vertically-standing one at the main entrance, are contorted and porous — two great qualities for passage of qi (氣), the invisible life force or energy that resides in every living thing.

Others are grouped strategically to make beautiful rockeries in the middle of water while some others are top heavy giving the impression of “clouds floating in the sky.” All serve as resting points for visiting doves, pigeons and other birds.

Water, the nurturing, yielding or yin element, is a necessary counterpoint to the hard, vertical, or yang elements such as rocks and buildings. The water bodies found in Shuangxi Park are rather murky and opaque in appearance, as algae can be found hugging the surface and edges. This green blanket is considered to be symbolic of life and adds to the overall serenity of the garden.

When my kids were younger, I took them to these nature-mimicking oases for fish-feeding, bird watching and picnics. Now I visit them for mindful, spirit-lifting moments of solitude because a meticulously planned traditional Chinese garden is like a composition that is never completely revealed. No wonder people who discover their beauty visit them again and again and again.

Shuangxi Park and Chinese Garden is located at 309 Fulin Rd, Taipei City (台北市福林路309號). Open 24 hours. Admission is free.

From an anonymous office in a New Delhi mall, matrimonial detective Bhavna Paliwal runs the rule over prospective husbands and wives — a booming industry in India, where younger generations are increasingly choosing love matches over arranged marriage. The tradition of partners being carefully selected by the two families remains hugely popular, but in a country where social customs are changing rapidly, more and more couples are making their own matches. So for some families, the first step when young lovers want to get married is not to call a priest or party planner but a sleuth like Paliwal with high-tech spy

With raging waters moving as fast as 3 meters per second, it’s said that the Roaring Gate Channel (吼門水道) evokes the sound of a thousand troop-bound horses galloping. Situated between Penghu’s Xiyu (西嶼) and Baisha (白沙) islands, early inhabitants ranked the channel as the second most perilous waterway in the archipelago; the top was the seas around the shoals to the far north. The Roaring Gate also concealed sunken reefs, and was especially nasty when the northeasterly winds blew during the autumn and winter months. Ships heading to the archipelago’s main settlement of Magong (馬公) had to go around the west side

When Portugal returned its colony Macao to China in 1999, coffee shop owner Daniel Chao was a first grader living in a different world. Since then his sleepy hometown has transformed into a bustling gaming hub lined with glittering casinos. Its once quiet streets are now jammed with tourist buses. But the growing wealth of the city dubbed the “Las Vegas of the East” has not brought qualities of sustainable development such as economic diversity and high civic participation. “What was once a relaxed, free place in my childhood has become a place that is crowded and highly commercialized,” said Chao. Macao yesterday

For the authorities that brought the Mountains to Sea National Greenway (山海圳國家綠道) into existence, the route is as much about culture as it is about hiking. Han culture dominates the coastal and agricultural flatlands of Tainan and Chiayi counties, but as the Greenway climbs along its Tribal Trail (原鄉之路) section, hikers pass through communities inhabited by members of the Tsou Indigenous community. Leaving Chiayi County’s Dapu Village (大埔), walkers follow Provincial Highway 3 to Dapu Bridge where a sign bearing the Tsou greeting “a veo veo yu” marks the point at which the Greenway turns off to follow Qingshan Industrial Road (青山產業道路)