May 11 to May 17

He first shouted in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese), “You don’t need to tie my hands or cover my eyes, for I have the blood of the Japanese running through me! If you have to blame a criminal, I alone will suffice!”

He then switched to Japanese for his last words: “Long live the Taiwanese!”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

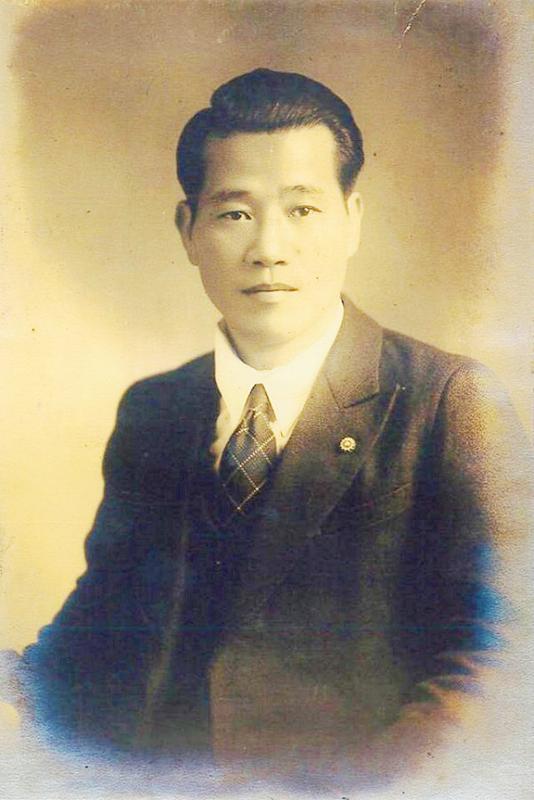

Tang Te-chang (湯德章) met his end at the age of 40 at the hands of Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops on March 13, 1947, one of countless victims in the aftermath of the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was brutally suppressed by the KMT. Born to a Japanese father and Taiwanese mother, his last words encapsulated his lifelong conflict of being descended from both the colonizers and the colonized.

In his official report, then-governor general Chen Yi (陳儀) partially blamed the uprising on Taiwanese being deeply “poisoned” by the Japanese, and that “lackeys” of the former colonial master instigated the revolt. As such, Tang became the ideal target to blame for the events that took place in Tainan.

“Aren’t you Japanese? Why don’t you go back to Japan?” a cellmate recalls the soldiers asking him at one point. “I was born in Taiwan, I was raised in Taiwan. Am I not Taiwanese?” he replied. “No, you’re Japanese,” the soldier said. “Then please interrogate me in Japanese, otherwise I won’t say a word.”

Photo courtesy of MarkTwain Production

Tang stayed true to his vow despite being tortured for days, possibly saving the lives of many Tainan citizens. For his bravery, the Tainan City Government dedicated a memorial park to him and observes the day of his death as “Justice and Courage Memorial Day.”

Tang’s name has been in the news over the past few weeks because his former residence was going to be demolished. Late last month, it was temporarily listed as a historical relic, its fate to be decided this month.

BETWEEN WORLDS

Photo courtesy of China Daily News

As a former Tainan police officer who defied the odds and passed both bar and civil servant exams in Japan, Tang had plenty of promising job offers in Tokyo. But in 1943, he made the perilous journey back home during the height of World War II.

Ryusho Kadota, who published a biography on Tang in 2017, writes that he had plenty of reasons to return home. His mother refused to move to Japan and, since his father died when he was young, he strongly identified with his Taiwanese heritage. When people asked about his decision, however, he would half-jokingly tell them that he couldn’t stay because his mother wouldn’t be able to buy her favorite betel nuts in Japan.

By returning home, Tang avoided the 1945 firebombing of Tokyo, but in those turbulent times, there wasn’t really a place that was safe.

Tang’s father, Tokuzo Sakai, came to Taiwan shortly after Japan took over Taiwan in 1895 to serve as a police officer. He met his future wife, Tang Yu (湯玉), through the job, and the two married in 1902, although Taiwanese-Japanese unions only became legal in 1933.

In 1915, the Tapani Incident broke out in southern Taiwan when Yu Ching-fang (余清芳) appointed himself Grand Marshal of the Benevolent Nation of the Great Ming (大明慈悲國) and declared war on the Japanese colonial government. The rebels attacked several police stations before they were crushed, and Sakai died in one of the attacks. Tang was eight years old.

Although the reality was that Taiwanese were treated as second-class citizens, the incident was the last of numerous Han Chinese armed revolts against Japanese rule (Aborigines would continue fighting). Tang was aware of this despite the loss of his father, Kadota writes, and often struggled with his identity.

Tang’s family fell into poverty. Since the marriage wasn’t legal, they were not compensated for Sakai’s death. Tang went by his mother’s surname, and Kadota writes, “he was still treated unfairly; his Japanese blood did not help.”

‘PRIDE OF TAINAN’

Despite dropping out of high school, Tang followed his father’s footsteps and became a policeman. He became a household name in Tainan after apprehending a wanted criminal and quickly rose through the ranks, although his reputation was tarnished by his refusal to give preferential treatment to a prominent Japanese man in a dispute with a Taiwanese.

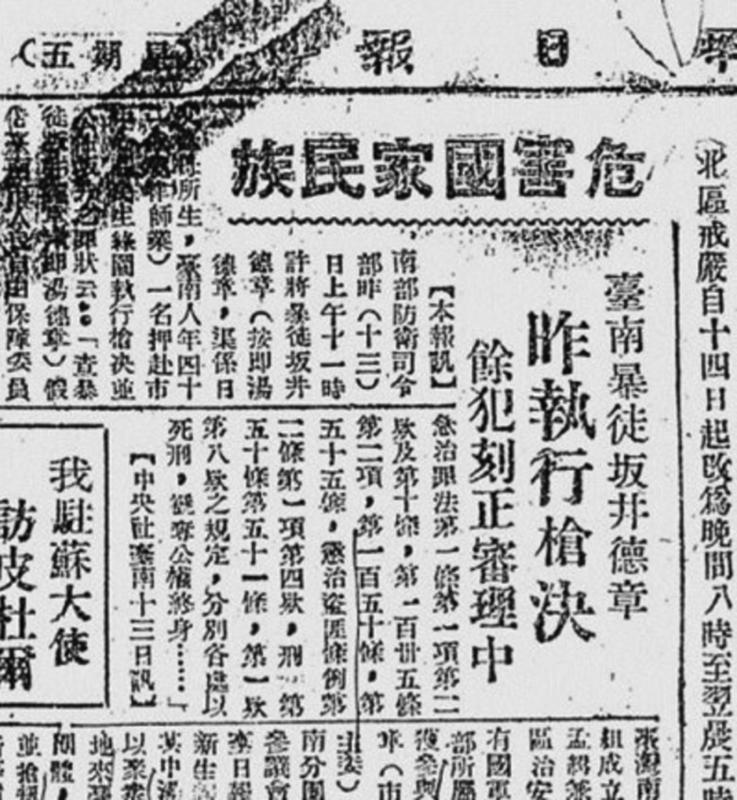

Tang eventually decided that only by becoming a lawyer could he carry out true justice, and at the age of 32 he quit the force and headed to Tokyo. He earned his high school qualifications and passed each subsequent hurdle with flying colors. His achievements made the headlines back home — one article stated that he “made Tainan proud.”

Only two years after he achieved his dream, World War II ended and the Japanese left. Tang was serving as a Tainan city assemblyman when he heard news of the 228 Incident in Taipei. Many people in Tainan also took up arms, while the newcomers from China shuttered their shops and went into hiding. Despite suffering from malaria, Tang took part in Tainan’s temporary committee of prominent citizens to deal with the unrest.

Tang knew that if the situation in Tainan escalated, the citizens would surely be subject to violent retribution by government troops. He successfully carried out his plan to stop local unrest while promising to demand that the government rectify its misdeeds and make Taiwan a true democracy. By March 5, the situation in Tainan had largely quieted down.

However, the government’s reinforcements soon arrived from China and began killing and arresting anyone suspected of being involved with the uprising. The troops soon reached Tainan, and Tang was one of the many arrested — but not before burning the list of those involved.

The authorities knew that Tang convinced many Tainan citizens to lay down their arms, and they wanted names. He was tortured and branded the Japanese instigator of the rebellion in Tainan, which fit Chen’s narrative that the incident was mainly caused by those who were still loyal to the former colonial government.

He was paraded through town before the final bullet pierced his skull.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has