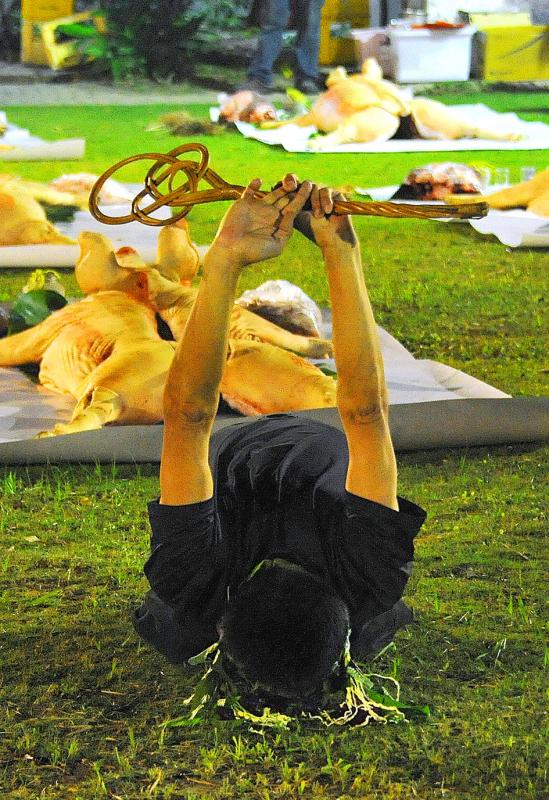

Huang Jung-fong (黃榮豐) is trembling on the ground, making retching sounds while clutching a ceremonial staff. He gets up, raises his arms to the sky and walks toward a group of white-robed villagers, delivering divine instructions that kick off the Pataran community’s annual Night Ceremony (夜祭).

Traditionally, a female shaman called an angi (尪姨) would perform the rituals, but Pataran hasn’t had one for as long as its residents can remember. In fact, before Pataran revived its Night Ceremony in 1999, its residents had lost their identity as indigenous Siraya along with most of their original language and culture, save for one thing: the worship of Alid, their collective ancestral spirit. Instead of a statue, Alid is represented with ceramic urns filled with sacred water.

“My grandparents never mentioned anything related to Siraya,” says Yang Chun-sheng (楊俊陞), head of the Tainan City Soulang Pataran Community Development Association. “But they often reminded me to celebrate Alid’s birthday on the 29th day of the third lunar month. Nobody really knew the significance of it.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Alid’s birthday fell on Tuesday of last week. Starting at dawn, people from surrounding villages made their way to Pataran’s Cingchang Temple (慶長宮), a typical Taoist establishment, paying tribute to Guanyin and other deities from the Han Taiwanese pantheon before bringing three ritual items — betel nuts, rice wine and glutinous rice cakes — to the shrine dedicated to Alid in the back.

Being the only preserved link to their ancestral culture, Alid worship remains the focal point of Pataran’s quest over the past two decades to reclaim their identity, beginning with the revival of the Night Ceremony the night before Alid’s birthday.

During this year’s event, which was significantly pared down due to the COVID-19 pandemic, participants spoke of their reverence for Alid and their ongoing efforts to understand what it means to be Siraya.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

“We worship Taoist deities here too, but since I was young I have felt that it was Alid who watched over me, and later over my children. Only after I started working did we find out that we were Siraya,” says Yang Yu-chen (楊玉真). “I started learning about my identity bit by bit, and whenever I have time I’ll try to learn more.”

CULTURAL LOSS

In the old days, Pataran was the center of the Siraya territory of Soulang, one of the ethnic group’s four major settlements on the Tainan plain. Being closest to the ocean, the Siraya of Soulang encountered the Dutch as early as 1623 — a year before they established a colony to the south. Han Chinese settlers soon started arriving en masse, mixing with the local population as well as encroaching on their land.

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

While Taoism was allegedly brought to Pataran by a Han Chinese immigrant who married into a local family, villagers continued to worship Alid at home and in a number of private shrines. In 1946, a spirit medium relayed a divine message to move all the urns to the current location, which became today’s Lichang Temple (立長宮) in 1955.

Superficially it resembles a concrete Han Chinese shrine, but in place of the figurine there is a tablet inscribed with the Chinese transliteration of Alid (阿立祖) and about 20 urns of different shapes, sizes and styles.

A Chinese couplet adorns the entrance: “A bite of betel nut to worship Alid, a thousand pots of aged wine to remember our ancestors.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

Cingchang temple was added in 1971 for Taoist deities after obtaining Alid’s permission. After 1999, a Siraya-language sign was attached to the entrance: kuva ki Alid (shrine for Alid).

The cultural erosion in Pataran was more severe than the other four Siraya villages that still perform the Night Ceremony, all of which lie in less coveted territory closer to the Central Mountain Range, and thus were subject to less outside influence.

The village of Kabuasua was originally settled by Pataran villagers who migrated due to Han Chinese encroachment. According to Siraya activist Alak Akatuang, they rarely intermarried with Han Chinese and preserved more Siraya culture, although they kept it hidden until the late 1990s when they began to revive their culture and seek official recognition.

The wave of cultural reawakening spread to Pataran, who sent villagers to Kabuasua to learn about the ancestral ways that they had lost. However, the Siraya remain unrecognized by the central government, only gaining recognition from the Tainan County Government (today’s Tainan City Government) in 2005.

‘INTERIM SHAMAN’

Although he has fond memories of the times when Alid’s birthday was a grand affair, Huang never heard of the term Siraya until around 1999. As he greets guests from other Siraya communities before the Night Ceremony, he laments that the local population is dwindling as young people leave for the cities. Few return for the festivities since it often falls on a weekday.

When the Night Ceremony was first revived, the Pataran community enlisted the help of the angi from Kabuasua. Huang’s father, a Taoist spirit medium, became the interim shaman after he allegedly became possessed during a ceremony and started mimicking the angi’s movements. After he suffered a stroke, Pataran asked Kabuasua for help again until Huang assumed the role in 2009.

“Alid sought me out,” he says.

Each village’s event varies, and sometimes even the deity is different. Kabuasua, for example, worships a female Alid, while Pataran’s is male.

The two components of Pataran’s Night Ceremony is the pig sacrifice and qianqu (牽曲), where female dancers link hands, sing and move in a circle around a large urn.

QUEST FOR IDENTITY

Yuko, one of the few Pataran residents to take up a Siraya name, is old enough to remember when they were still seen as a different people from their neighbors. Children from other villages often taunted him as huana (番仔), a derogatory term in Hoklo that means savage or barbarian.

“I got into so many fights because of that,” he says. “But I was mad just because they made fun of me. I had no idea that it had anything to do with our identity.”

By the time Yang Yu-chen grew up, in the 1970s, he says that he never felt any difference between him and his Han Taiwanese neighbors — except that his family worshipped Alid in addition to Guanyin.

In addition to encroachment and assimilation, many Siraya from the Pataran community hid their identity in the past to avoid discrimination.

Huang Mei-li (黃美麗) says that her husband comes from a merchant family who passed themselves off as Hoklo during the Japanese-era census for business purposes, and while her mother comes from a historically Siraya village, they never discussed their ancestry.

Yuko estimates that about one-third of Pataran’s residents were registered under the Japanese-era census as shou (熟), meaning “civilized” indigenes, as opposed to 80 percent in Kabuasua.

Despite the uncertainty, Huang was the first Pataran resident to learn the qianqu dance from Kabuasua village. She also picked up Siraya-style cross-stitch embroidery to decorate ceremonial clothes and other items. Her bag is adorned with a traditional pattern she found from the National Museum of Taiwan History, in addition to the word tabe, which means “hello” in Siraya.

Just two decades into the revival process, the villagers seem to still be figuring out what it means to be Siraya. Yuko says that out of the shrinking population, only about half are interested in further exploring their identity.

During conversations with the villagers, questions about Siraya identity seem to always lead back to Alid. Yang Chun-sheng, for example, was driven by the many extraordinary “miracles” that he attributes to Alid after he moved back in 2003.

“My children are studying in other cities, but whenever they come back I take them to the shrine to pray to Alid,” Yang Yu-chen says. “They are also quite passionate toward Alid. I hope that if they end up working in the south, they can become more involved.”

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

For the past century, Changhua has existed in Taichung’s shadow. These days, Changhua City has a population of 223,000, compared to well over two million for the urban core of Taichung. For most of the 1684-1895 period, when Taiwan belonged to the Qing Empire, the position was reversed. Changhua County covered much of what’s now Taichung and even part of modern-day Miaoli County. This prominence is why the county seat has one of Taiwan’s most impressive Confucius temples (founded in 1726) and appeals strongly to history enthusiasts. This article looks at a trio of shrines in Changhua City that few sightseers visit.