Within 10 minutes of the train pulling into Chaojhou (潮州) in Pingtung County, I’d retrieved my bike from a paid-parking compound and initiated the fitness tracking app on my phone. Just one thing bothered me: The color of the sky.

I cycled southeast, passing the shuttered Dashun General Hospital (大順醫院). Given everything that’s going on in the world, I couldn’t help but think: If the government needs extra facilities to handle the COVID-19 epidemic, this sizable building could perhaps be brought back into service.

After crossing Highway 1 (台1線), I skirted a settlement established after 2009’s Typhoon Morakot disaster, during which mountain villages throughout the south were devastated by floods and landslides. Whereas most of Chaojhou’s residents are Hakka, the families who’ve moved into New Laiyi (新來義部落) in Sinpi Township (新埤鄉) since 2012 are indigenous.

Photo: Steven Crook

Taking Road 185, I headed southeast across the Linbian River (林邊溪) and into Siangtan (餉潭). I kept going through the heart of the village — which is big enough to have its own elementary school and police station — to Longtan Temple (龍潭寺). I felt a few drops of rain when I paused by the pond in front of the shrine. Judging by the trash around the water, people often come here to engage in the secular pursuits of smoking and drinking.

I didn’t expect much of the temple, so I wasn’t disappointed. There’s nothing remarkable about the building or its hilly backdrop. Proceeding north on County Road 113 (屏113), I hadn’t got more than 1km when a spatter of rain developed into a heavy shower. Rather than stop and throw on my anorak, I decided to keep going in the hope I’d find shelter just around the corner.

Wet through at the shoulders and knees, I trespassed onto a hillside farm where tarpaulins kept a table and a few chairs dry. I didn’t see anyone, so I sat down and watched the ground turn to mud.

Photo: Steven Crook

Three-quarters of an hour later, when the rain eventually eased off, I witnessed something I’ve seen before in similar conditions: Hundreds of dragonflies, appearing out of nowhere, buzzed energetically at head height for several minutes before dispersing.

Passing pineapple fields, mango orchards, and papaya plantations, I continued north on County Road 113. An ornate archway decorated with indigenous motifs prompted me to make a quick detour to the community known to Mandarin-speakers as Wenle (文樂部落), and to Paiwan folk as Pucunug. In the village itself, I’m sad to report, there’s nothing half so appealing as the arch.

I was now in Laiyi Township (來義鄉), where I planned to visit another four villages. But first I needed to refuel. After grabbing some rice and soup in Gulou (古樓), the busiest part of the township, I recrossed the river, hoping to take County Road 113 inland to its eastern end, then return via County Road 110 (屏110) on the north side of the river.

Photo: Steven Crook

Before I got far, a sign told me the road was closed. However, I could see asphalt extending around the corner, so I persevered. Finding the surface too slick for safe riding, I pushed on, figuratively and literally. Within a few hundred meters, the road disappeared beneath rocks and I admitted defeat. I hadn’t wasted much time, and the views up and down the valley had been pretty good.

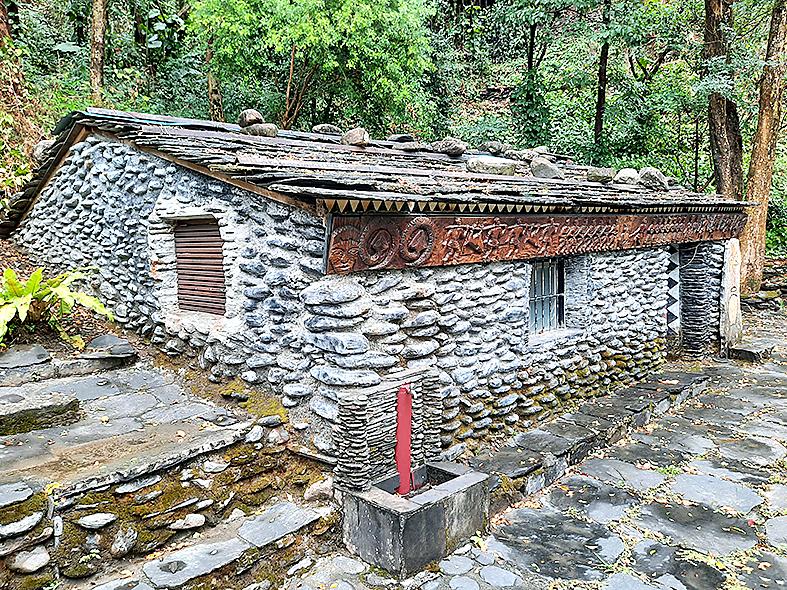

Siljevavaw Forest Park (喜樂發發森林公園), just east of Laiyi Elementary School (來義國小) on County Road 110, is an attractive spot. It’s no bigger than many city parks, but contains photogenic indigenous architecture and art.

A bust near the entrance honors Japanese hydraulic engineer Torii Nobuhei (1883-1946). I wasn’t familiar with his name, but from the Chinese-language plaque I gleaned that he’d planned and overseen the construction of key water-supply infrastructure in the valley. He is to the development history of the Chaojhou-Sinpi region what Yoichi Hatta is to the Chianan Plain (嘉南平原).

Photo: Steven Crook

The next stretch involved some uphill effort, but soon I was riding through the narrow streets of the village from which Laiyi Township takes its name. Three things made an immediate impression on me. First, even though part of the population has relocated to New Laiyi, there seemed to be quite a few people around. Second, rather than use Mandarin or Taiwanese, many residents were chatting to each other in Paiwan. Third, dead earthworms littered the road.

I scanned the hillside to the east for the ruins of Old Laiyi (舊來義), but didn’t see anything that resembled its old slate houses. Having run out of ridable road, I locked my bike and set off on foot along the riverbed.

Two pairs of towers are all that remain of suspension bridges. During the hour I spent hiking by the river, I came across numerous chunks of concrete, girder fragments, and other evidence of Mother Nature rejecting humanity’s efforts to penetrate the mountains.

Freewheeling back to Gulou took mere minutes, and where the townships of Laiyi, Sinpi, and Wanluan (萬巒) converge, I stopped at the first convenience store I’d seen in hours. Suddenly, I had to share the road with a dozen cars and just as many motorcycles.

I was back in the lowlands, that was for sure. At this point in the story, you might expect a lament on the themes of overcrowding and air pollution. But I made a point of staying off major roads as I approached the railway station at Sishi (西勢) in Jhutian Township (竹田鄉), and enjoyed the final third of the day’s ride (which totaled 64.7km) as much as the earlier parts.

Near Chihshan (赤山), I stumbled across a stretch of old Taiwan Sugar Corporation (台糖, TSC) railroad that’s being converted into a bicycle path. Avoiding the heart of Neipu (內埔), I joined County Road 48-1 (屏48-1), a route I hoped would go through quiet yet quaint villages.

I guessed right. Where County Road 48-1 is also known as Liren Road (里仁路), I stopped to gawk at a picturesque ruin and the exceptionally colorful shrine cater-corner from it. A septuagenarian on a bicycle pulled up, and asked me if I wanted to buy a house. I replied that I just wanted to take photos — but I’ve long thought this corner of Pingtung County could be a great place to call home.

Steven Crook has been writing about travel, culture, and business in Taiwan since 1996. He is the co-author of A Culinary History of Taipei: Beyond Pork and Ponlai, and author of Taiwan: The Bradt Travel Guide, the third edition of which has just been published.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Last week the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) said that the budget cuts voted for by the China-aligned parties in the legislature, are intended to force the DPP to hike electricity rates. The public would then blame it for the rate hike. It’s fairly clear that the first part of that is correct. Slashing the budget of state-run Taiwan Power Co (Taipower, 台電) is a move intended to cause discontent with the DPP when electricity rates go up. Taipower’s debt, NT$422.9 billion (US$12.78 billion), is one of the numerous permanent crises created by the nation’s construction-industrial state and the developmentalist mentality it

Experts say that the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on Friday was likely the strongest to hit the country in decades, with disaster modeling suggesting thousands could be dead. Automatic assessments from the US Geological Survey (USGS) said the shallow 7.7-magnitude quake northwest of the central Myanmar city of Sagaing triggered a red alert for shaking-related fatalities and economic losses. “High casualties and extensive damage are probable and the disaster is likely widespread,” it said, locating the epicentre near the central Myanmar city of Mandalay, home to more than a million people. Myanmar’s ruling junta said on Saturday morning that the number killed had