March 23 to March 29

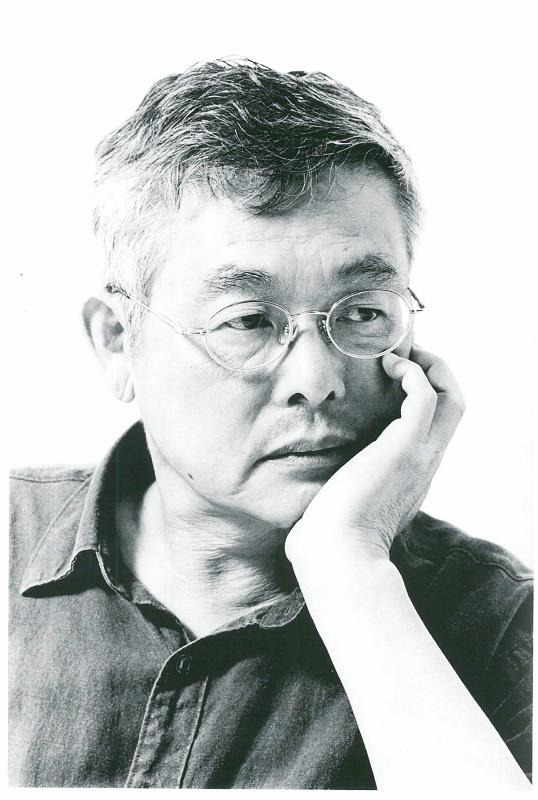

Yeh Shan’s (葉珊) prolific writing career came to an abrupt end in 1971 after publishing his poetry collection Legend (傳說). When he reemerged two years later at the age of 32 with the essay Annual Ring (年輪), he had become Yang Mu (楊牧).

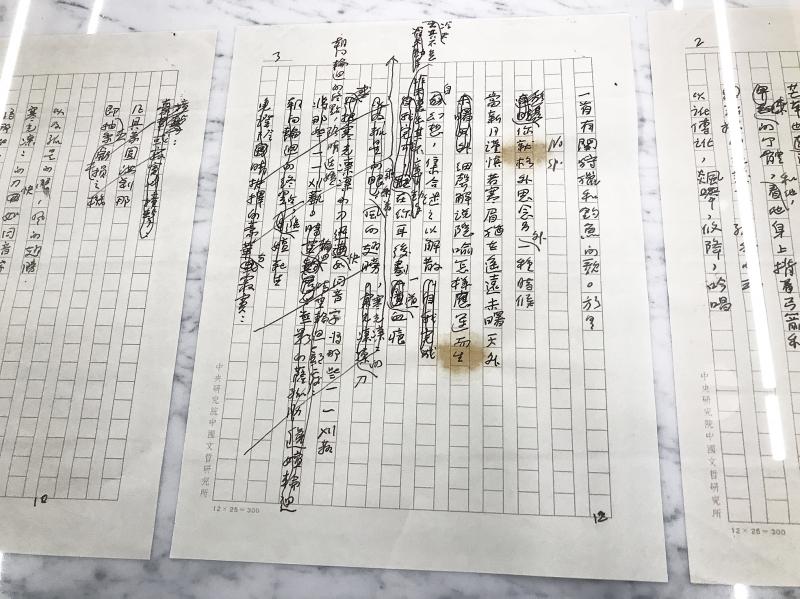

Yang foreshadowed Yeh’s demise in the foreword to Legend: “These past five years have been a rare confirmation that not even for a moment have I been able to persist with one style, one perspective and one technique; instead, amidst constant change, I’ve never stopped rejecting, denying and destroying my past … This [has happened several times before] but never as cruel and thorough as the past five years.”

Photo: CNA

Yeh represented the romanticism, sentimentality and innocence of the poet’s youth. When he became Yang, he “gained a layer of calmness and subtlety, and started to create works that criticized society,” states the introduction to the Public Television Service documentary Towards the Completion of a Poem: Yang Mu (朝向一首詩的完成).

“Change is not easy, but not changing means death. Change is painful, but change is the truth of life,” he says in the documentary. As we all know, the only thing that doesn’t change is death (and taxes).

When Yang died on March 13, he was known as one of Taiwan’s most acclaimed literary figures, leaving behind an impressive body of poems, essays, critiques and translations. Before he died, his wife Hsia Ying-ying (夏盈盈) read him his work Cloud Ship (雲舟):

Photo: CNA

All the tangibles and intangibles have been explored

now we with our bright hearts are determined to reach the other side of

the stars, on a ship with pure white sails, or on the wings

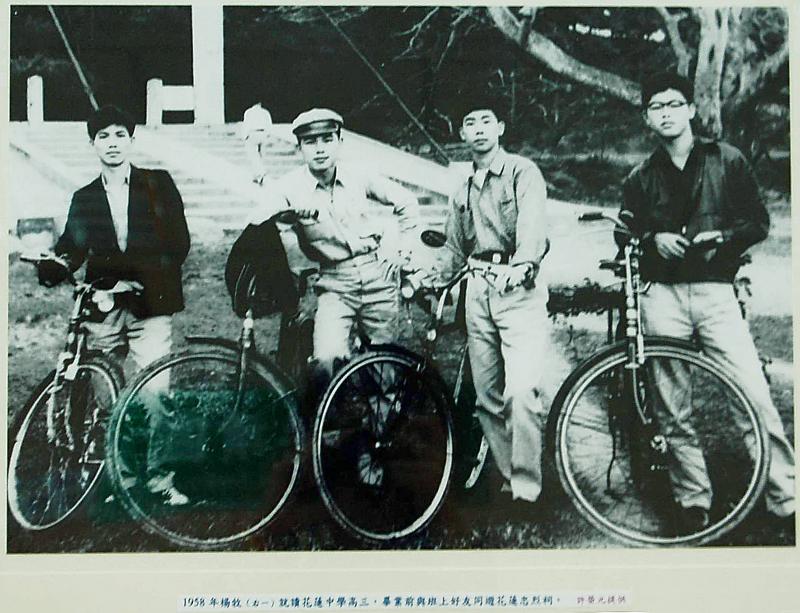

Photo courtesy of Hualien County Cultural Affairs Bureau

of the archangel, who has been waiting for us all along

many years ago an extant prophetic book

foretold a time when all will be transported

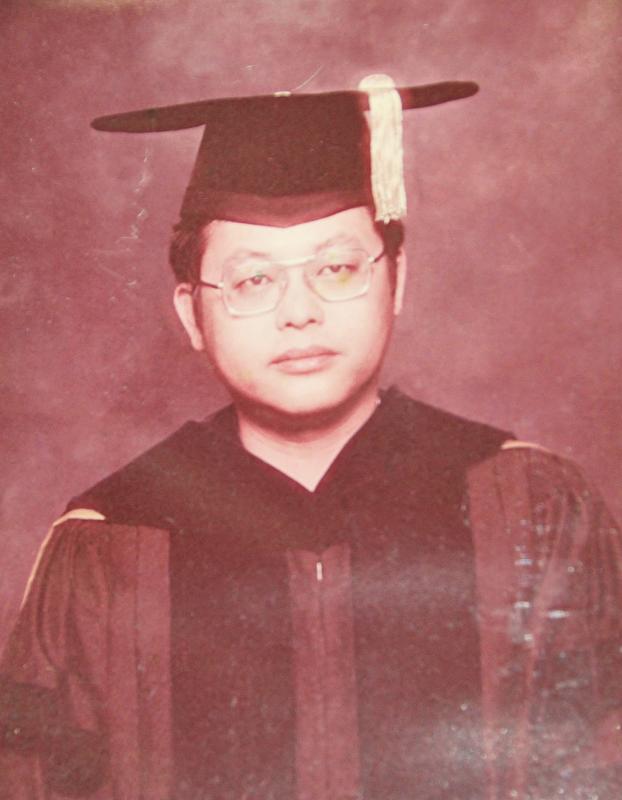

Photo: Hua Meng-CHIN, Taipei Times

in the melody of a song. In steady twilight breeze

on a gently swaying ship of clouds, the joyful soul

UNDER MOUNT QILAI

Long before Yang became Yeh Shan, he was Wang Ching-hsien (王靖獻). He was born in Hualien in 1940, just before World War II heated up in the Pacific.

“The flames of war burned in the distant sky, but hadn’t reached my ocean, my small city, my courtyard covered with a dense canopy of leaves,” Yang writes in Memories of Mount Qilai (奇萊前傳), a collection of autobiographical essays.

The book opens with Yang as an introspective and observant child, listening to the sound of the Pacific ocean, observing the sunlight piercing through the leaves while a beetle glided to the ground, and crunching the fallen leaves with his wooden sandals.

“The flames of war had not reached Hualien.”

Eventually they did, as the Americans conducted airstrikes in the area as part of its bombardment across the Japanese colony. Yang recalls that the Japanese were building an airstrip nearby for kamikaze pilots when the war suddenly ended, sparing his hometown from further destruction.

When Yang turned 16, he began submitting poems to the Public Opinion Press (公論報) poetry supplement under the pen name Yeh Shan, eventually starting a poetry magazine with an older schoolmate.

At the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature at Tunghai University, Yang voraciously devoured the works of British Romanticist poets such as William Wordsworth and John Keats. At the age of 20, he self-published his first poetry collection On the Water Margin (水之湄) through his father’s printing press. It was proofread by his sister.

In the afterword, he writes: “The greatest satisfaction for a poet is when he writes for a star, or a cloud, that star, that cloud understands his language; when he writes for a person, that person understands his language. I can’t remember how many poems I’ve written, but in my heart, I remember all the people that appeared in my poems, even if they don’t know it. That is sadness. A person always carries some sadness, but that of a poet is especially heavy.”

LEAVING THE PAST

The transformative five years that Yang mentions in the foreword of Legend begins around the time he earned his master’s degree from the Iowa Writers Workshop at the University of Iowa. When he first arrived, he would write letters to his literary hero Keats, who had been dead for close to 150 years. Upon graduation, he wrote to Keats for the 15th and final time: “I find the rainbow boring and excessive, I feel the dullness and clamor of the spring rain, I can no longer grasp the joy of birds chirping. I watch feathers fall from the maple trees, and the elm fruits cover the sky, but those early infatuations can dissipate. Poet, this is my last letter to you.”

Yang thought of becoming a war correspondent, but instead he moved to Berkeley to continue his studies in 1966. It was a hotbed of liberalism and social activism in the 1960s, and Yang arrived just after the Free Speech Movement protests of the 1964-1965 school year at UC Berkeley, one of the first of many demonstrations held on college campuses throughout the decade.

But Yang had little interest in social issues when he arrived, writes Chang Hui-ching (張惠菁) in his biography Yang Mu (楊牧). He was on a scholarship that also covered his living expenses, and didn’t have to venture much into the real world just yet. In 1967, the anti-Vietnam War protests reached its height at Berkeley, and Yang often saw students clashing with the police. He became particularly incensed when he watched the government uses airplanes to spray tear gas over students.

He fully felt the passion and anger of the protestors, Chang writes, but he did not participate, although the activities still made an impact on him as an observer.

“Berkeley made me open my eyes and observe and recognize this society with urgency,” Yang writes. “While knowledge is power, knowledge should not be limited to academic institutions. Knowledge is only power when it is liberated and applied to the reality of society.”

Yang’s concern was not just about how to become more involved with society, but how to become involved without being swallowed whole. In 1970, the baodiao (保釣, “protecting the Diaoyutais”) student movement exploded among Taiwanese students in the US, and “everyone became involved in different ways to different degrees,” he writes. Many of his classmates didn’t finish their studies as a result.

Yang earned his PhD in 1971. He secured a job in Seattle, and returned to Taiwan for the first time in eight years in 1972.

“On the second day back in Hualien, Yang woke up at 4am and went for a stroll. By the fields, he saw people bent over planting water spinach. He looked at the mountain that had not changed, and suddenly tears fell from his eyes,” Chang writes. In Seattle, he wrote about how salmon always return to where they are born, but people easily get lost.

Later that year, he became Yang Mu.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.