The ancient Aboriginal settlement of Kucapungane (舊好茶, Jiuhaocha) is steeped in myth. Rukai elders tell of its formation over 600 years ago, when hunters were tracking a clouded leopard that eventually stopped to rest by a river. Deeming it a sacred spot, the hunters built up a community of slate houses close by, which would grow to nearly 300 residences over the following centuries.

For Shikieyan, however, the reason for the settlement is far more prosaic.

“In the winter, Guhaocha’s (古好茶) rivers dry up,” he tells me last month, referring to an even older settlement. “So they moved [to Kucapungane].”

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

We are sitting outside a slate house in Kucapungane that Shikieyan renovated at a table topped with a large piece of slate and looking past a slate terrace to valley below.

Shikieyan traces the route he takes to get to Guhaocha — up a portion of the facing 3,200-meter Beidawu Mountain (北大武山), over a ridge and down a ravine. It’s a trip he says he hasn’t made in over 15 years, though he continues to hunt in the area.

“Come back and I’ll take you there,” he says, grinning at me.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

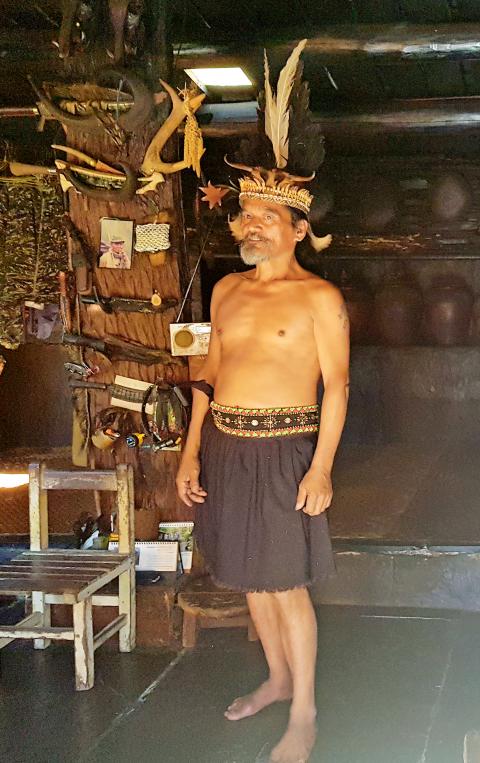

That’s hilarious. The five-hour trek up to Kucapungane, at a height of about 1,000 meters, almost finished me, and Shikieyan knows it. If I were to embark on a full day hike to the older settlement even deeper in the mountains, he’d almost certainly have to leave me there with his ancestors. But this is part of his appealing swagger — his six-decade plus frame looking half that: Shikieyan knows that this is his land and that we are his guests.

Known in these parts as “the hunter,” Shikieyan is one of the three remaining inhabitants (and a dog named Tiaopi, 調皮) living permanently in the abandoned settlement in Wutai Township (霧台), Pingtung County. The hunter and his wife, Kuan Kuei-yin (官桂英), have been generous enough to allow our group of six hikers and two guides to sleep the night in one of their slate homes — complete with wild animal pelts hanging from the rafters, a central wooden pillar adorned with hunting knives and dozens of wild boar jaws dangling from a string in a bedroom, a testament to his namesake. Over 24 hours, Shikieyan will tell me his story, why the endlessly fascinating village was abandoned in the early 1970s and the history of the Kucapungane Rukai, of which I subsequently learn only 3,000 remain.

TREK TO KUCAPUNGANE

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

But first, the trek in.

Our guide Xiaoyang (小楊) stands on an embankment overlooking Pingtung’s Ailiao River (隘寮溪) at the foot of Jingbu Mountain (井步山) and assembles, in groups of three, cigarettes and betel nuts on the surface of a large rock. After lighting the cigarettes, he pulls out a plastic bottle, takes a swig and spits it into the wind three times, each time misting the air with the scent of rice wine. The ritual finished, Xiaoyang tells me the mountain gods have been appeased.

Xiaoyang’s gesture has an understandable logic. As our group drove the 90 minutes from Kaohsiung to Wutai Township, much of our conversation revolved around landslides and flooding, buried villages and enormous body counts caused by the region’s many typhoons. As we travel up the mountain and back the next day, I will find evidence that Xiaoyang has performed this ritual several times.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Coming from the somewhat orderly streets of Taipei, it’s easy to forget that nature’s fury determines the landscape for Taiwan’s east coast — usually due to earthquakes and typhoons. Fortunately for us, February brings little rain to this region and the once-raging river in front of us has shrunk to a stream, though its eroded embankments rise in places to 50 meters and the truck-sized boulders scattered about, remind us of the river’s potential fury.

We maneuver up a rockslide to reach the trail proper and as we ascend from 300 meters to 400 meters, kilometer-long landslides scar the mountains far and near. The temperature is an unseasonable 27 degrees Celsius, the overgrown jungle in parts shading us from the sun.

Half-way up, we encounter a Rukai hunter resting in the shade of a rocky overhang and next to a tiny stream that brooks out of the mountain and into a large plastic bucket.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

“It’s clean,” he says. “But watch out for the leeches.”

Upon closer inspection, there are a half dozen tiny black leeches inching around the bucket’s rim. I pass on filling up my water bottle, after one of our guides tells the story of a hiker who got one lodged in her nose.

The hunter then questions our motives for hiking the trail. As with all Aboriginal land, permission must be granted by authorities or connections made with locals before starting a trek.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

“So you know [Shikieyan],” he says after one of our guides tells him where we will stay. With that, he motions us on.

We next encounter the same hunter 100 meters up at a clearing with a one-room shelter made from slate. He proceeds to cut up lengths of plastic hose, which I assume will be used further up the mountain to control the flow of a brook or stream because he soon affixes a dozen or so 2.5-meter long hoses to his rucksack and rifle. While the hunter goes about his business, our party packs up, having rested 30 minutes and eaten lunch.

The rest was needed. Most of our party are experienced hikers, with one Canadian having completed the baiyue (百岳), or 100 peaks over 3,000 meters, unheard of for a non-Taiwanese; another, an American in rubber boots, will soon be guiding groups up other treks such as Jade Mountain (玉山).

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

Most of the trek up is strenuous, but not dangerous until we get to within a few hundred meters of the settlement. At this point, the path narrows and much of it is carved out of the side of a cliff, a rope separating climber and the valley below.

DISAPPEARING COMMUNITY

Just as my quadriceps are seizing up and I’m wondering if I’ll make it to Kucapungane, it comes into view. A long slate terrace with mountain views on the right brings us to two of the settlement’s habitable abodes, on the left. Shikieyan’s home has a fire pit built into the covered terrace and seats over a dozen. After the sun goes down, this will be our barbeque space.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

There is little time to take this in, however, as one of our guides instructs us toward a waterfall beyond the village, which will remove the hike’s five-hour dirt and sweat. We walk past dozens of abandoned slate homes being reclaimed by the jungle, and reach the waterfall and its pool of clear water teeming with schools of tiny fish and tadpoles.

After lounging in the pool’s cool water, we return refreshed to Shikieyan’s house. The pace at Kucapungane is languid. Our guides have intentionally given us several hours free time before dinner to rest, explore or talk with Shikieyan and his wife, who are happy to tell us their story.

Kuan, a Hakka with plains Aborigine blood, originally met the hunter while on an ecology tour two decades ago. They fell in love, married and had two children.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

“One child is overseas and rarely returns. That’s her choice, that’s her life,” Kuan says in a manner suggesting that she’d rather have her daughter home more often.

The hunter tells me that the village contained 200 to 300 residences during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan and after World War II, as well as three houses of worship and a school.

World Monuments Watch, a nonprofit that draws attention to important artistic treasures throughout the world, listed Kucapungane as endangered in 2016.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

The community, it writes, “remains almost complete in plan, with 163 houses, many built from hand-cut black and grey shale slabs... The Rukai still see the village as their spiritual homeland and continue to visit the site, with a few families making frequent trips, though they do not have the capacity to repair and preserve the buildings alone.”

Further into the settlement’s ruins stands the shell of the small church, the cross on its facade the only evidence that a Christian house of worship existed here. The boxy building stands out both because it doesn’t conform to any of the other architectural styles and because it is the only ruin of hundreds that I encounter that’s made from cement. The school has been lost to the jungle.

“My class had 37 students ... less than half are alive today,” Shikieyan says.

Photo: Noah Buchan, Taipei Times

He adds that, like many of the other community members his age, he left the village when he was young and traveled to work in Taipei. By his early thirties, though, he’d had enough of “working for other people” and returned to the village. He’s been here ever since.

He immediately began renovating the slate home we are sitting out front of, a project that took over a decade to complete. He also returned to a hunter’s lifestyle. Kuan, who often follows him out on the hunt, tends an elaborate garden.

At one point, Kuan produces two photo albums. The first documents Shikieyan and others renovating the slate house, complete with bas relief panels of Rukai myths and skeletons of wild animals. The other contains dozens of photographs of Shikieyan hauling down the mountain slaughtered wild boar, goat and deer. The pictures, many taken by Kuan, have a heroic aspect — in one, the hunter carries a boar that’s almost his size, another shows him shirtless, his strong body carrying slate stones.

Kuan keeps her garden tidy and, at one point during our two-day stay, picks several leafy vegetables, climbs on to the roof of their one-level home shingled with slate and lays them out to dry beside solar panels, installed in 2018.

We’d been warned before embarking on the trek that Kucapungane has no electrical outlets to charge our phones — and trying to get a signal involves walking about half a kilometer to a clearing where there is reception. Few of us bother.

A single lightbulb above the fire pit is the only artificial light illuminating our evening cookout, and walking 10 meters in any direction leads to darkness, the sky offering a dazzling array of stars. As I stand on a ridge away from the fire pit looking into the starry distance, I imagine my eyes seeing the same scene that hunters saw centuries ago.

Back at the house, Shikieyan wants to talk politics. Not about the recent presidential election or about the Kaohsiung mayor’s recall. He’s still miffed, he says, that he had to take down a sculpture that the royal family is only allowed to display because it signifies their high status. All politics is local.

Shikieyan says he got in trouble years back from community elders for moving one of these snakehead sculptures to his terrace. Decidedly not of the royal family, he was eventually pressured to take it down. Needless to say, a day-tripper like myself can only gain a limited understanding of the hierarchical complexity of this settlement and its seven tiers of abodes: royal family at the top, plebes at the bottom.

Yet the high status of the royal family could not resist the pull of modernity, and Shikieyan says that in 1974 community elders decided to move to a new village: Tulalegele (Xinhaocha, 新好茶), at the base of the mountain.

TULALEGELE INUNDATED AND RINARI

The move proved both a blessing and a curse.

Tulalegele found its Rukai residents living in the typical Taiwanese buildings with modern amendments such as electricity, modern healthcare and education and easy transportation to the city. But the Rukai language and traditions, Shikieyan says, which could have remained more cohesive in Kucapungane, began to disappear.

Our group has left Kucapungane, trekked back down the mountain to the Ailiao River. Before we load our gear into the truck that brought us in, we ask our driver to stop at Tulalegele on the way back. When we arrive, there is little to see.

Typhoon Morakot, which struck in August 2009, brought three meters of rain in 48 hours, causing massive flooding and landslides. The only visible evidence of Tulalegele is the upper facade of a church that once served as the center of the community. It continues every year to sink into oblivion.

Fortunately, the residents of Tulalegele escaped before their village was inundated. Siaolin (小林) was not so fortunate. A little after Morakot struck, a mudslide and damming of the Nanzihsian River (楠梓仙溪) buried the village — and 600 of its residents.

With Tulalegele buried, the Kucapungane Rukai were forced to move again, to a community called Rinari.

The contrast between Rinari and Tulalegele, let alone the old settlement, couldn’t be more marked. Rinari looks like any American suburb, with its paved streets laid out in a grid, SUVs parked in driveways and children playing basketball in the local park. The only visible hint that this is a Rukai village are the symbols on the side of the homes. Here, the Rukai have become as domesticated as we are in Taipei.

Guhaocha, Kucapungane, Tulalegele, Rinari — the story of these four settlements, is the story of one Aboriginal community that is constantly on the move. At first, over centuries and, more recently with modernity, over decades. What links them together are the water sources that sustain life and take it away.

It’s a shame that the effort to construct Rinari and maintain as much as possible the traditions of the Rukai hasn’t been made for Kucapungane.

Shikieyan says the ruins of this magnificent settlement today represents the hunter-gatherer lifestyle of the Rukai community that is, like the slate houses, slipping away — one that he tries his best to keep alive by educating younger members of the Rukai community and outsiders like us who make the trek.

“Maybe the next time you return I’ll be gone,” he says. “And so will my knowledge of our ancestral hunting grounds.”

For your information:

Blue Skies Adventures organizes trips to Kucapungane. For more information,

visit: www.blueskiesadventures.com.tw

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei’s (艾未未) famous return to the People’s Republic of China (PRC) has been overshadowed by the astonishing news of the latest arrests of senior military figures for “corruption,” but it is an interesting piece of news in its own right, though more for what Ai does not understand than for what he does. Ai simply lacks the reflective understanding that the loneliness and isolation he imagines are “European” are simply the joys of life as an expat. That goes both ways: “I love Taiwan!” say many still wet-behind-the-ears expats here, not realizing what they love is being an

In the American west, “it is said, water flows upwards towards money,” wrote Marc Reisner in one of the most compelling books on public policy ever written, Cadillac Desert. As Americans failed to overcome the West’s water scarcity with hard work and private capital, the Federal government came to the rescue. As Reisner describes: “the American West quietly became the first and most durable example of the modern welfare state.” In Taiwan, the money toward which water flows upwards is the high tech industry, particularly the chip powerhouse Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co (TSMC, 台積電). Typically articles on TSMC’s water demand

Every now and then, even hardcore hikers like to sleep in, leave the heavy gear at home and just enjoy a relaxed half-day stroll in the mountains: no cold, no steep uphills, no pressure to walk a certain distance in a day. In the winter, the mild climate and lower elevations of the forests in Taiwan’s far south offer a number of easy escapes like this. A prime example is the river above Mudan Reservoir (牡丹水庫): with shallow water, gentle current, abundant wildlife and a complete lack of tourists, this walk is accessible to nearly everyone but still feels quite remote.