Dec. 23 to Dec. 29

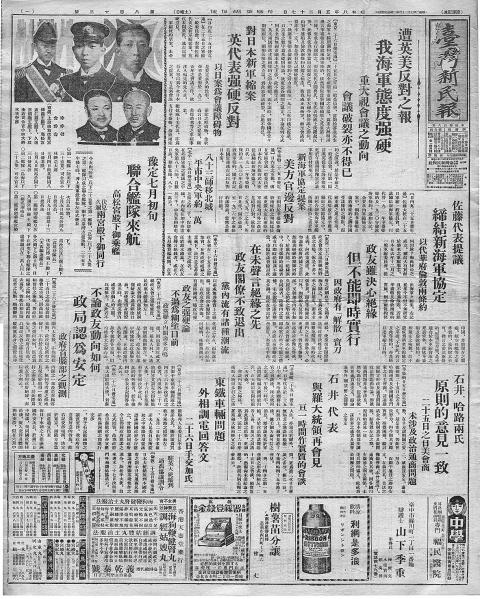

Wu San-lien (吳三連) made his last stand against the Japanese authorities in 1939 when he published and distributed a book criticizing its unfavorable rice policy.

The resistance movement in Taiwan was shut down by then as the Japanese tightened control over the colony after the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937. Wu, who was running the Tokyo bureau of Taiwan New Minpao (台灣新民報), agreed to take on the issue. He had a history of causing trouble for the Japanese, and writes in his memoir, “I don’t own any farmland. But for the righteousness of my people, I gave my all for the farmers of Taiwan. This was my most meaningful and proudest moment.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Wu felt something was wrong, however, when he was fired and recalled to Taiwan. Instead of heading home, he fled to China.

Born into poverty in rural Tainan in 1899 and not entering first grade until the age of 13, Wu’s personal journey is quite remarkable as he was involved in significant events in Taiwan’s history throughout his life.

LIFE OF DEFIANCE

Photo courtesy of Southern Taiwan University of Science and Technology

Given his family circumstances, Wu was lucky to have finished secondary school. He insisted on studying in Japan despite fierce objection from his family, who desperately needed money.

“To this day, I don’t know where my determination came from,” he writes, getting his wish through a scholarship from the wealthy Banciao Lin Family (板橋林家).

During his time in Japan, he joined the anti-colonial resistance and was put on a government blacklist for making anti-Japanese speeches across Taiwan on behalf of the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會) in 1923. He graduated from business college in 1925 and joined the Osaka Daily News.

Photo courtesy of National Museum of Taiwan Literature

“I realized that there was little racial discrimination in the journalism field, and the thinking was more liberal too,” he writes.

Wu remained in Japan for seven years before returning home to help out at Taiwan New Minpo, which was the first Taiwanese-run daily newspaper in the colony. Wu was the only one among the anti-colonial activists who had any journalism experience, and took on four jobs including managing editor. He recalls that when the authorities blacked out parts of the newspaper they didn’t like, the paper would print the pages with the redacted marks to demonstrate to the readers the lack of freedom of speech and “incite their anti-Japanese sentiments.”

Wu was still in self-exile when the Japanese surrendered in August 1945. He writes that he had three wishes — to witness the Republic of China flag replace the Japanese one atop the Governor General’s Office, to hear the Japanese apologize for their mistreatment of Taiwanese and to build a new Taiwan by Taiwanese hands.

He ended up staying in China for an extra year trying to save Taiwanese who worked for the Japanese during the war and were branded by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) as hanjian (漢奸, traitors to Han Chinese). During this year, he had already heard about the government’s misrule in Taiwan, and had no illusions when he set out for Taiwan at the end of 1946.

INDEPENDENT POLITICIAN

In hope of changing things, Wu ran for the National Assembly, earning a seat as the top vote-getter in Taiwan. This was the body that would be known as the “Ten-thousand year congress (萬年國會),” as they remained in place for the next 44 years due to the KMT’s wartime provisions.

In 1950, KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) personally appointed Wu as mayor of Taipei despite him never joining the party. Wu recalls that he didn’t accomplish much as most of his time was spent dealing with the massive influx of refugees and soldiers from China. The city was in chaos, with illegal settlements sprouted up everywhere and the streets strewn with garbage and human excrement due to the lack of flushable toilets. Space was so lacking that people dug up Japanese cemeteries and even erected structures on the streets.

Despite significant public criticism, Wu became Taipei’s first elected mayor in 1951. His next stint was in the Taiwanese Provincial Assembly, where he was known as one of the famed “Five Dragons and One Phoenix” group of non-KMT politicians who did not hesitate to speak out against the government and pushed for Taiwanese autonomy and democracy.

In 1960, Wu was involved in another significant event — Lei Chen’s (雷震) failed attempt to form an opposition party. Wu was urged to help lead the party, but he distanced himself from the movement out of concern for his business interests and family. Plus, he saw that clashing directly with the KMT was futile.

Lei was soon arrested and thrown in jail for 10 years.

At this point, Wu quit politics and focused on building his business and running the Independent Evening Post (自立晚報). He cofounded three schools, including Taipei Private Yan Ping High School, and set up the Wu San Lien Awards to support local writers and artists. His foundation invited Nobel Prize-winning, anti-communist author Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to Taiwan in 1982, causing a massive media frenzy.

The late historian Chang Yan-hsien (張炎憲) writes that Wu was one of the few people who were trusted by both the KMT and the opposition during the rise of the latter in the 1970s. When pro-democracy protesters clashed with the police in the Kaohsiung Incident of 1979, Chang writes that Wu urged then-president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) to excise restraint and not turn it into another 228 Incident, a 1947 uprising that was brutally suppressed.

Two years after Wu’s death on Dec. 29, 1988, his descendants, along with historians and academics, established the Wu San Lien Foundation for Taiwan Historical Materials (吳三連台灣史料基金會), which has printed a number of invaluable historical books, especially focusing on the 228 Incident and Taiwan’s struggle for democracy. Anyone who has done research on Taiwan’s past should have come across his name at one point.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Dec. 16 to Dec. 22 Growing up in the 1930s, Huang Lin Yu-feng (黃林玉鳳) often used the “fragrance machine” at Ximen Market (西門市場) so that she could go shopping while smelling nice. The contraption, about the size of a photo booth, sprayed perfume for a coin or two and was one of the trendy bazaar’s cutting-edge features. Known today as the Red House (西門紅樓), the market also boasted the coldest fridges, and offered delivery service late into the night during peak summer hours. The most fashionable goods from Japan, Europe and the US were found here, and it buzzed with activity

During the Japanese colonial era, remote mountain villages were almost exclusively populated by indigenous residents. Deep in the mountains of Chiayi County, however, was a settlement of Hakka families who braved the harsh living conditions and relative isolation to eke out a living processing camphor. As the industry declined, the village’s homes and offices were abandoned one by one, leaving us with a glimpse of a lifestyle that no longer exists. Even today, it takes between four and six hours to walk in to Baisyue Village (白雪村), and the village is so far up in the Chiayi mountains that it’s actually

These days, CJ Chen (陳崇仁) can be found driving a taxi in and around Hualien. As a way to earn a living, it’s not his first choice. He’d rather be taking tourists to the region’s attractions, but after a 7.4-magnitude earthquake struck the region on April 3, demand for driver-guides collapsed. In the eight months since the quake, the number of overseas tourists visiting Hualien has declined by “at least 90 percent, because most of them come for Taroko Gorge, not for the east coast or the East Longitudinal Valley,” he says. Chen estimates the drop in domestic sightseers after the

US Indo-Pacific Commander Admiral Samuel Paparo, speaking at the Reagan Defense Forum last week, said the US is confident it can defeat the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the Pacific, though its advantage is shrinking. Paparo warned that the PRC might launch a “war of necessity” even if it thinks it could not win, a wise observation. As I write, the PRC is carrying out naval and air exercises off its coast that are aimed at Taiwan and other nations threatened by PRC expansionism. A local defense official said that China’s military activity on Monday formed two “walls” east