Technology has a bad rep these days. Each news cycle seems to bring more reports of data mining, fake news and other social ills of the digital age. Big Tech has fallen from its pedestal, increasingly criticized for monopolizing data, finance and power in ways that have had unforeseen consequences on the non-virtual world.

These thoughts were never far from my mind at the 17th Digital Art Festival, now showing at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Taipei (MOCA, Taipei) until Nov. 10. Walking into a sinister soundtrack of electronic instruments, I’m prepared for doomsday predictions of how human civilization has wrought our own destruction through technological evolution.

Instead, levity abounds. If digital art is a commentary on the relationship between humanity and technology, then this festival paints a redemptive picture. Artworks revel in the unique aesthetic of the digital age, its connection to (rather than severance from) the natural sciences and how it enhances our capacity to create and relate.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

VIEWER INTERACTION

This also means a particularly fun time for visitors, as unlike traditional media, almost every artwork is designed for some form of viewer interaction. These range from the obvious — virtual reality (VR) technology — to the more experimental — brain waves and blockchain.

Hung Yu-hao’s (洪譽豪) The Hallway of City No. 1 (城市穿廊計畫No. 1) transforms Taipei’s oldest neighborhoods into a pathway that viewers “walk” through on a manually-powered treadmill. Even as it captures rich, lived-in architecture, the still landscape, which dissolves into unrecognizable points of light upon closer inspection, is a melancholy reminder of transience and how such historic spaces are being destroyed by the march of progress.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

In Shota Yamauchi’s Zone Eater, players use VR controllers to enter the “souls” of characters and perform actions. Through character design, the game plays with the concept of the uncanny valley, which hyothesizes that humanoid objects which imperfectly resemble us can trigger feelings of revulsion and eeriness.

Aesthetic theories aside, faith in technology is strongest in the works that push the boundaries of VR for practical application. Bio I/O by Chun-cheng Hsu Laboratory (許峻誠實驗室), based out of the National Chiao Tung University Institute of Applied Arts, expands VR from its usual visual and aural applications to the other senses. Contraptions worn on the arms and face not only allow viewers to navigate a fantastical seaworld, but also simulate the physical sensation of moving through a body of water.

Li Chien-yu (李建佑), one of the project’s two creative and technical directors, says that the technology has applications for people with visual impairments as it uses the same underlying principles as Braille. Even under art museum conditions, this is a convincing version of a future in which such body augmentations become the norm, especially if the line between human and cyborg continues to blur. After all, I already think of my smartphone as an extension of my hand.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

Themes of surveillance, control and dehumanization are still on the cards, such as in Semi Su’s (蘇紳源) Lines — Online (界—在線), which uses computer vision and 3D rendering to convert museum visitors into “data subjects.” German artist Clemens von Wedemeyer’s film Transformation Scenario pits algorithmic crowd simulations against footage of real-life crowds to ominous effect.

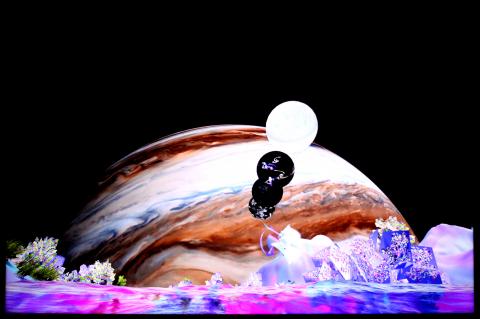

There are still some doomsday narratives, although these tend to be backdrops to scenarios that deepen a sense of humanity. Wu Tzu-ning’s (吳梓寧) Metaverse 2.0 (魅塌域2.0) uses VR to plunge viewers into a wasteland filled with the detritus of civilization and its memories, provoking a reflection on the value of objects in everyday life.

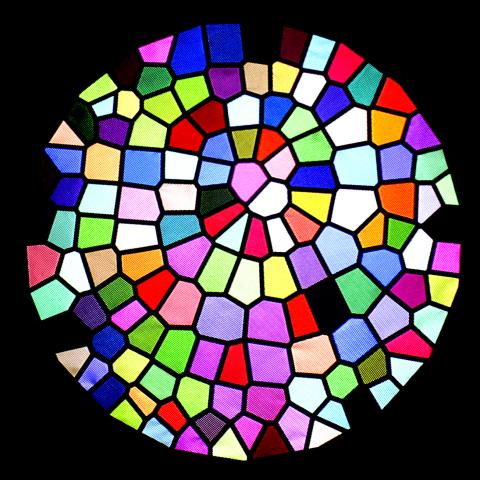

At other times, however, the exhibition is a reminder that principles of computing, also found in nature, can produce wonder and whimsy. Voronoi Guess 2 (沃羅諾伊的猜想2) by Lee Chia-hsiang (李家祥) uses a Voronoi diagram — an algorithm that partitions a plane into regions — to produce a stained glass window-lookalike on the wall of the museum. Viewers manipulate its appearance using a sensor, resulting in surprising and beautiful configurations.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

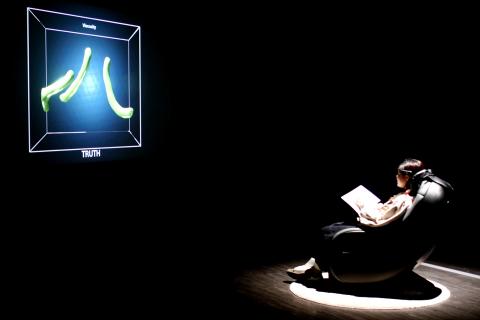

The festival saves its showstopper for the last gallery. At first glance, Value of Values, a collaboration between French artist Maurice Benayoun, German artist Tobias Klein, Colombian artist Nicolas Mendoza and French composer Jean-Baptiste Barriere, resembles a sci-fi noir movie. People sit in pod-like chairs with sensors around their foreheads, staring expressionless into screens that project unrecognizable, pulsating forms.

Settling into my chair, the screen tells me to visualize the value of “kindness” and runs through a detailed list of attributes like color, radius and viscosity. I imagine a sunshine yellow blob in the shape of two outstretched palms.

I can’t be sure whether this part of the work is entirely performative or whether it’s actually tapping into my neurotransmissions. But what appears on screen is instead a brick-red object in the shape of a finger or a phallus, depending on scale.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

A gallery assistant comes over in amazement, because she hasn’t seen anyone create such a streamlined shape.

“Everyone else’s has things growing out all over the place,” she laughs. But while my attention is diverted, the shape starts spreading out.

After the visualization is complete, I get a QR code to scan my value into a virtual marketplace modeled after a cryptocurrency barter system. I start getting ideas about the radical democracy of the digital age, which allows us to create personalized experiences and even customized values. I whip out my phone to start trading.

Photo: Davina Tham, Taipei Times

Unfortunately, after a day of pondering how my experience of the world has been irreversibly altered by technological achievements, this is where technology fails me — my QR code doesn’t work.

ENDING HIV/AIDS STIGMA

Running concurrently with the Digital Art Festival is Interminable Prescriptions for the Plague (瘟疫的慢性處方), a co-presentation with the Taiwan HIVStory Association (臺灣感染誌協會) that will be on view until World AIDS Day on Dec. 1.

Located in MOCA Cube — a repurposed shipping container located outside the museum’s main building — the exhibition uses this open, public space to showcase activists’ efforts to enhance access to medical treatment and end the stigmatization around HIV/AIDS.

The works question stereotypes about HIV/AIDS by drawing thought-provoking links between other features of modern life.

Blockchain rears its head again here, as an analogy for HIV transmission. Positive Coin: Automatic Transaction Machine (帕斯堤貨幣: 自動交易機) by Lee Tzu-tung (李紫彤) transacts a “bionic currency” that has features of a virus — it grows but also expires, and is kept alive by paying a trading tax.

At the end of the trading cycle on Dec. 1, participants can exchange their coin for actual HIV/AIDS activism merchandise. Tickets to participate as a trader have sold out, but visitors can view the ATM and consider how values and attitudes shift when a virus is packaged as cryptocurrency.

Next to the ATM, the bathroom set-up in Lo Chih-hsin’s (羅智信) Like a filter, matters passed through you and became a part of you. (Twilight) (像是顆濾心,物質穿越過你便成為你的一部份(暮光之城)) is a tongue-in-cheek commentary on our fascination with blood and hygiene through contemporary vampire romance novels.

Compared to the museum’s immersive main presentation, these works lack breathing room in the relatively tight exhibition space. But the exhibition promises some engaging live presentations. On Nov. 3 and 17 respectively, Mandarin tours by intensive care physician Tu Han-hsiang (杜漢祥) and Taiwan Tongzhi Hotline Association director Ka Fei (喀飛) will flesh out the themes of the exhibition as they relate to the experiences of the HIV/AIDS community.

And on Dec. 1, American poet and performance artist Brad Walrond will present Blood Brothers, a multi-disciplinary work integrating interviews with Taiwan’s HIV/AIDS activists and data on the epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in Taiwan.

Following the rollercoaster ride of 2025, next year is already shaping up to be dramatic. The ongoing constitutional crises and the nine-in-one local elections are already dominating the landscape. The constitutional crises are the ones to lose sleep over. Though much business is still being conducted, crucial items such as next year’s budget, civil servant pensions and the proposed eight-year NT$1.25 trillion (approx US$40 billion) special defense budget are still being contested. There are, however, two glimmers of hope. One is that the legally contested move by five of the eight grand justices on the Constitutional Court’s ad hoc move

Stepping off the busy through-road at Yongan Market Station, lights flashing, horns honking, I turn down a small side street and into the warm embrace of my favorite hole-in-the-wall gem, the Hoi An Banh Mi shop (越南會安麵包), red flags and yellow lanterns waving outside. “Little sister, we were wondering where you’ve been, we haven’t seen you in ages!” the owners call out with a smile. It’s been seven days. The restaurant is run by Huang Jin-chuan (黃錦泉), who is married to a local, and her little sister Eva, who helps out on weekends, having also moved to New Taipei

The Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS) told legislators last week that because the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) are continuing to block next year’s budget from passing, the nation could lose 1.5 percent of its GDP growth next year. According to the DGBAS report, officials presented to the legislature, the 2026 budget proposal includes NT$299.2 billion in funding for new projects and funding increases for various government functions. This funding only becomes available when the legislature approves it. The DGBAS estimates that every NT$10 billion in government money not spent shaves 0.05 percent off

Dec. 29 to Jan. 4 Like the Taoist Baode Temple (保德宮) featured in last week’s column, there’s little at first glance to suggest that Taipei’s Independence Presbyterian Church in Xinbeitou (自立長老會新北投教會) has Indigenous roots. One hint is a small sign on the facade reading “Ketagalan Presbyterian Mission Association” — Ketagalan being an collective term for the Pingpu (plains Indigenous) groups who once inhabited much of northern Taiwan. Inside, a display on the back wall introduces the congregation’s founder Pan Shui-tu (潘水土), a member of the Pingpu settlement of Kipatauw, and provides information about the Ketagalan and their early involvement with Christianity. Most