Aug. 5 to Aug. 11

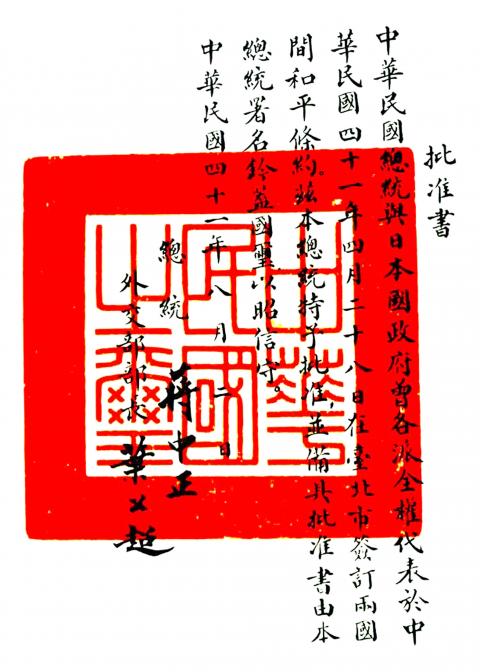

Sixty-seven years after its ratification and 47 years after its termination, the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty (中日和平條約) is still often brought up during debates regarding Taiwan’s sovereignty.

One camp uses it as proof that Japan formally handed its former colonies of Taiwan and Penghu to the Republic of China (ROC) government, while the opposing camp argues that Japan never specified who it would hand its former colony to, making the ROC’s 74-year rule over Taiwan illegitimate.

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The debate was reignited this week as a new high school history textbook suggested that Taiwan’s sovereignty may have never been determined, citing both the Sino-Japanese Peace Treaty and the Treaty of San Francisco, where Japan merely relinquished their claims to Taiwan and Penghu. Former president Ma Ying-jeou (馬英九) of the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was among those who sounded off, stating that the ruling party should not doubt its own sovereignty and that it has long been clear that the ROC is the rightful ruler of Taiwan.

This week’s column will not delve into the debate, which should be familiar to anyone who follows the news and politics; instead it will look at the circumstances under which the treaty was signed and the arduous process it took to complete the deal.

FROM FOE TO FRIEND

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

At the end of World War II, KMT leader Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) announced that he wouldn’t seek war reparations from a defeated Japan, which remained under Allied occupation. In 1949, he recruited a team of Japanese military advisers, who came to be known as the White Group (白團).

The KMT was still reeling from its defeat at the hands of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and expulsion from China. Under the Cold War and especially with the outbreak of the Korean War, the government started seeing its former nemesis of Japan as an ally in the united front against communism.

In June 1950, Chiang announced the importance of fostering good relations with Japan.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“Although we emerged victorious in the eight-year war against Japan,” Chiang says, “we still ended up in total failure due to the Soviets instructing the communist bandits to revolt. As a result, both [China and Japan] are losers now … We have come to an understanding that Japan cannot invade us again, and we cannot view Japan with animosity. The two sides need to cooperate so we can both survive and prosper.”

Interestingly, Chiang here admits that the KMT victory over Japan was not completely his — a line that was different from the propaganda the government would later spread in Taiwan.

“We should not look down on Japan because they lost the war. In fact, we should reflect on how we were able to defeat Japan. To be honest, half of our victory was due to our appropriate doctrine and policies, but the other half was due to support from the US and other allies. Did we really defeat Japan on our own? Despite the dire situation of our country today, the Japanese officers are willing to risk their lives to come to Taiwan to help us resist communism … they are willing to fight alongside us, and we should give them the respect and courtesy they deserve.”

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

Three months later, the two sides signed an official trade agreement. Soon, it came time to determine the future of Japan. The US was worried that if the Allies occupied Japan for too long, resentment among its citizens would grow, allowing communism and other undesirable elements to infiltrate the nation. Plus, a stable and prosperous Japan would mean a strong ally in East Asia, especially with China having already fallen.

WHICH CHINA?

On Sept. 4, 1951, the Allied powers convened in San Francisco for a five-day meeting to sign a peace treaty with Japan. Representatives from 49 countries were present, but the one country that suffered the most from Japanese atrocities was missing: China.

This stemmed from a disagreement as to which China to invite: the US supported Chiang’s Taiwan-based ROC, while the UK had already switched recognition in January 1950 to the People’s Republic of China. The conclusion was to sign the treaty without China, and Japan could later choose which “China” to sign a separate peace treaty with.

The Associated Press reported the decision in July 1951, adding that the US expected Japan to negotiate with “Free China,” which was basically Taiwan by that point.

Taiwan was not happy, of course. Control Yuan President Yu Yu-jen (于右任) expressed shock toward the outcome, stating: “We fought Japan for the longest out of all countries and sacrificed the most. The ROC is a UN member and has wholeheartedly supported its charter and policies. This is not only the greatest international trickery, it’s also a blemish on human history that will never go away.”

After two months of protests, the treaty was signed anyway. Despite the reluctance of then-Japanese prime minister Shigeru Yoshida, the US and UK insisted that Japan choose which China to negotiate with. Japan seemed reluctant to make a move, at one point even considering negotiating with the CCP under UK pressure.

The UN convened in November that year, and the Soviet Union’s attempt to invite the People’s Republic of China was shot down, 37-4. After US diplomat John Foster Dulles visited Tokyo in December, he received a telegram from Yoshida, promising that Japan would sign with the ROC.

TENSE NEGOTIATIONS

Since the ROC was on the winning side of the war, the treaty was to be signed in its capital of Taipei. After much back and forth about the format of the treaty, the Japanese delegates arrived in Taipei on Feb. 17, 1952 and negotiations began three days later.

The ROC representative and Minister of Foreign Affairs, George Yeh (葉公超), presented a draft to the Japanese delegate Isao Kawada, a version largely identical to the stipulations of the Treaty of San Francisco. The Japanese rejected it. Yoshida did not seem to take the ROC seriously; several days earlier he called it a regional government that did not represent the whole of China. Kawada said that Japan merely wanted a simplified agreement that would mark the reopening of diplomatic relations, while Yeh insisted on a full treaty that reflected the ROC as the rightful ruler of China, a UN member and one of the former Allied powers.

After a whole month of negotiations, the two sides seemed to have reached an agreement. But on March 28, Kawada again rejected the agreement. Yeh refused to budge, leading to another impasse. Intense talks went on for another month, and Yeh was about to issue a final ultimatum when the treaty was finally signed on April 28. It went into effect on Aug. 5.

The treaty was terminated when Japan established relations with China in 1972.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has