July 22 to July 28

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, it was not uncommon for lovers who could not be together to drown themselves in the Tainan Canal. While the practice was eventually curbed, the love story of one of these couples — between a married man and a prostitute — lived on through Taiwanese operas and novels, spawning at least two feature films in the 1950s.

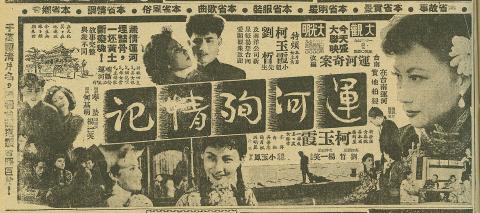

The version presented in the popular 1956 film The Canal Suicides (運河殉情記) told of the stark reality for many unfortunate women in Taiwan during those times. The protagonist, Chen Chin-kuai (陳金筷), was sold at a young age to another family as a foster daughter. The foster mother eventually sold her to a brothel, where she worked until she met a married man surnamed Wu (吳). Unable to change their circumstances, the lovers decided to end their lives in the canal.

Photo courtesy of Taiwan Historica

The foster daughter system was a mainstay of Taiwanese society, dating back to the time when Han Chinese first arrived. Farming households would often sell their daughters if they had too many children, keeping the boys for labor and to pass on the family name.

“With the rise of industrialization and urbanization, the weakening of traditional morals and problems within the [foster daughter] system itself, people started committing heinous acts under the guise of fostering a daughter,” Lee Chang-kuei (李長貴) writes in A Study of the Institution and Problems of Foster Daughters in Taiwan (台灣養女制度與養女問題之研究).

“Not all foster daughters are abused. Of course there are foster parents who dote on them as their biological daughters, but unfortunately that situation is rare. Most parents treat the foster daughters as commodities and hardly see them as human beings,” Lee continues.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

It wasn’t until the 1950s that former Taiwan Provincial Assembly member Lu Chin-hua (呂錦花), a former foster daughter herself, started a movement to help these women that the problem started to abate.

FOSTER ARRANGEMENT

Government statistics show that in 1958, close to when The Canal Suicides came out, there were 189,841 foster daughters in Taiwan. Lee writes that the system made sense in an agricultural society.

Photo courtesy of Open Museum

“It took about the same resources to raise a girl, but her ‘usefulness’ was far inferior to a boy. It was a ‘losing business,’ so they might as well ‘give’ the daughter at a high price to another family. That way, they not only received immediate profit, but also avoided having to pay her dowry in the future,” Lee writes.

The richer family who bought the girl could marry her to their son, take in a son-in-law or have her help with household chores. For them, it was a small price to pay, and the arrangements made both families happy.

While there were laws to protect the foster daughters, Lee writes that they were not enforced, nor did they have any restrictions on the type of person who could adopt them except that they had to be at least older by 20 years. The poor treatment entailed physical abuse including rape, forced prostitution, forced marriages, as well as confiscating their documents, restricting their movements and denying them formal education.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The issue got to the point where “between the 1950s and 1970s, the foster daughter system was seen as a vital cog to the sex industry,” Yu Chien-hui (游千蕙) writes in The Movement to Protect Foster Daughters in 1950s Taiwan (1950年代台灣的保護養女運動). Lee writes that the general impression in those days was: “There is nothing more poisonous than a foster mother” (無毒不養母).

MOTHER OF FOSTER DAUGHTERS

Born in 1909, Lu was one of the few lucky foster daughters who grew up in a loving household. She graduated from what is today’s Taipei First Girls’ High School, married into a prominent family and moved to China with her husband, Chen Shang-wen (陳尚文), in 1932. The pair returned in 1945 and became heavily involved in politics.

According to her biography on the National Museum of Taiwan History’s “Taiwan Women” Web site, Lu already watched over many abused foster daughters before she launched the movement. Her son Chen Tu-lung (陳獨龍) recalls young girls running into their home, still bleeding from their wounds, crying to Lu for help.

Women’s rights were on the rise and their roles expanding during that time, and Lu was also known as a skilled orator who was able to convincingly rally support for her cause. Coupled with her husband’s respected position in both the business and political world, she found plenty of backing.

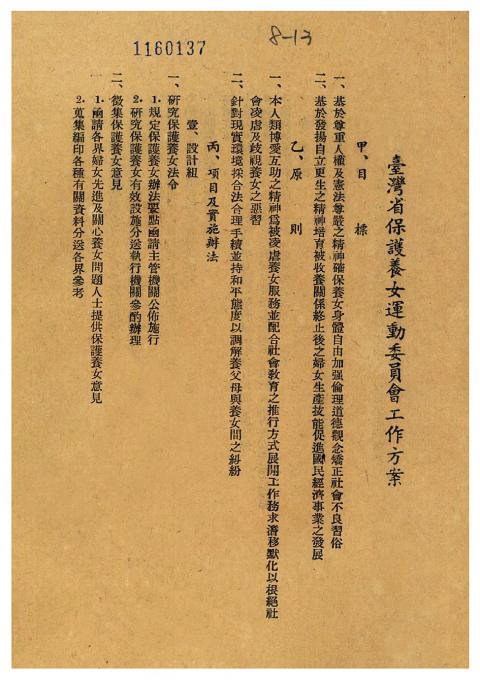

During a provincial assembly meeting in 1951, Lu brought up the importance of helping foster daughters, inviting three women to share their tragic experiences. The government response was sympathetic, and on July 24, the Taiwan Provincial Committee for the Movement to Protect Foster Daughters (台灣省保護養女運動委員會) was born. The committee established branches across the country, aiming to bring more public attention to the abuses, to investigate individual cases and to help them find a suitable husband or develop skills for employment outside of the sex industry.

After a failed attempt in passing a similar law in 1951, the Regulations on Improving Current Practice of Foster Daughters (臺灣省現行養女習俗改善辦法) was passed in 1956.

Operating out of a tiny office above a police station, the committee took on 967 cases in its first year of operation; by 1965 it had helped a total of 5,515 women.

On the fourth anniversary of the committee’s establishment, they held a mass wedding for 12 foster daughters whom they saved from being forced into unfavorable marriages. These mass weddings were held yearly. When the foster daughters reached the proper age to marry, Lu helped them find suitable husbands, paid for the wedding expenses and provided household goods for their new lives.

In 1966, Lu established a home for foster daughters, showing that the abuses were still taking place. However, society had taken note of the problem and newspapers started reporting more abuse cases; foster daughters also felt increasingly empowered to seek help.

By 1974, the issue had improved to the point where the committee was absorbed into the Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association (台灣省婦女會), where they continued to fight for a wider range of women’s rights issues.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has