April 22 to April 28

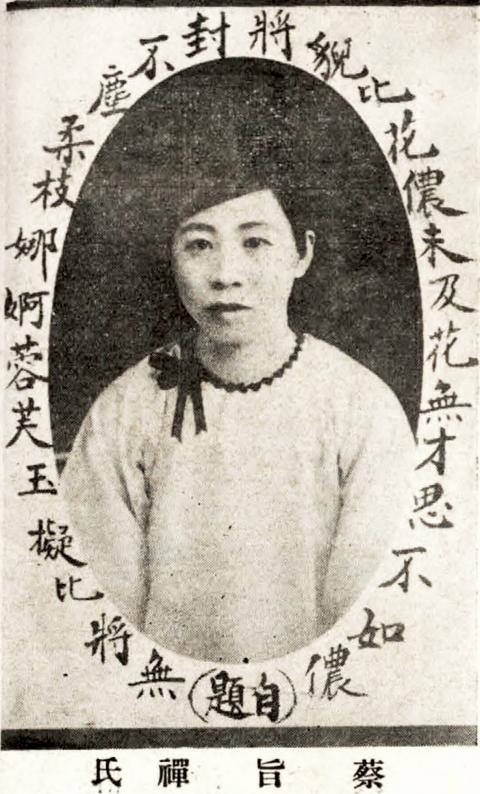

According to Penghu County records (澎湖縣志), Tsai Chih-chan (蔡旨禪) was born after her childless parents prayed to the Buddhist goddess of compassion, Guanyin (觀音).

“She was a virtuous and gifted child with great intelligence, distinguishing herself from her peers at a young age. She enjoyed embroidery and drawing instead of playing, and by the age of nine, she had become a vegetarian and devout Buddhist,” the records state about Tsai.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Whether true or not, embellished biographies involving deities are reserved for extraordinary people. Tsai was born in on April 28, 1900 in the Japanese-ruled backwaters of Penghu to parents of modest means — not exactly the right elements for a woman to make something of her life.

Tsai grew up to be a well-respected poet, her work appearing in numerous publications between 1923 and 1937. At the age of 24, she became Penghu’s first ever female Chinese-language teacher. When she accepted a teaching position in Changhua the following year, she named her school “Pingquanxuan” (平權軒), literally the “Equal Rights Pavillion.” Before Tsai left Penghu, she wrote a poem to her classmates, one verse expressing her desire to “make my name known as a woman.”

Tsai wasn’t the only prominent female poet in those days. In a 1933 island-wide poetry anthology from which Tsai’s only known photo was procured, there were several other women featured in the author introduction pages. Notable names include Huang Chin-chuan (黃金川), who authored Taiwan’s earliest known anthology of classical poems by a woman, and Chang Lee Te-ho (張李德和), another accomplished poet and painter who later served in the Taiwan Provincial Assembly.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Historian Lee Yu-lan (李毓嵐) writes in the study that the 1920s saw the awakening of Taiwanese women as they started participating in public affairs; the local newspapers ran many columns discussing new attitudes toward females regarding marriage, education, work and even entering politics.

The same period, for example, produced Taiwan’s first female physician Tsai A-hsin (蔡阿信, born 1899) as well as Hsu Shih-hsien (許世賢, born 1908), Taiwan’s first woman to earn a doctorate degree. Both have been featured in previous Taiwan in Time columns on June 5, 2016 and June 24 last year, respectively.

A CELEBRATED DEBUT

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Although women’s roles were still fairly restricted at the turn of the 20th century, change was brewing. The year Tsai was born, a group of intellectuals and businessmen formed the “Taipei Natural Feet Association” (台北天然足會), which aimed to stop the crippling practice of foot binding for women, which was more prevalent among the upper class. The group also encouraged women to go to school and handed out badges to women who unbound or never bound their feet.

Other groups worked with the government to set up vocational training centers for women, encouraging them to step beyond home labor. The government’s aim was not so much to promote gender equality, but to increase Taiwan’s labor force to speed up the colony’s industrial development.

Tsai reveals in a poem that she decided by the age of nine to never marry and devote herself to Buddhism so she could support and take care of her parents. It may seem odd today, but Tsai was proud of her decision, which was widely praised by her contemporaries as virtuous.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Wei Hsiu-ling (魏秀玲) writes in Study of Tsai Chih-chan and her Poetry and Painting Collection (旨禪詩畫集) that Tsai likely never received a formal Japanese education, instead acquiring her literary skills from private tutors who taught Chinese classics. One of her teachers was Chen Hsi-ju (陳錫如), who hailed from the same township in Penghu. Before returning home in 1923, Chen was known for training 12 talented female writers in what is today’s Kaohsiung area, and Tsai commends Chen in a 1927 anthology for his efforts in preserving Chinese education under colonial rule and encouraging female education.

After just a year under Chen, Tsai submitted her first poem to Penghu’s Xiying Poetry Society (西瀛吟社), surprising her peers by winning one of the top prizes. Her male peers praised her accomplishment — Yen Chi-shuo (顏其碩) wrote three verses celebrating the feat, and the national Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報) also reported her win, calling it a “rare occurrence.”

In April 1924, Tsai took on her first batch of students. The Tainan New Post (台南新報) noted on April 23 that she was the first female to teach Chinese in hundreds of years of Penghu history.

TUTORING TAIWAN’S ELITE

By the end of 1924, Tsai packed her bags and took her parents with her to Taiwan, where she was hired as a teacher in Changhua. This was again reported in the Tainan New Post, which marked it as a milestone for female accomplishment.

She was later employed by the prominent Wufeng Lin family (霧峰林家) to educate the female members of the household, becoming close with family head Lin Hsien-tang (林獻堂) and his wife, Yang Shuei-hsin (楊水心). Through them she gained access to many high society functions, including Lin’s cultural organization Yixinhui (一新會), which boasted 65 females out of about 300 members — an impressive gender ratio for those days. The women were not only encouraged to attend public functions and speak up, they actively participated as decision makers.

Lin was the head of the Taiwan Cultural Association (台灣文化協會), which added “respecting the character of women” to its annual objectives in 1923. While there was much discussion on the role of women domestically in the 1920s, many upper class Taiwanese also had the chance to travel abroad and see how differently women were treated. Lin, in particular, took note of the respect and opportunities given to Western women when he spent over a year traveling the world in 1927 and 1928. As always, this attitude wasn’t across the board as members protested Lin giving equal rights to women in the Taiwan Cultural Association. Lin responded that women should be treated as human beings and that their inferiority was due to lack of education.

When Tsai headed to Hsinchu for another teaching post in 1932, the Shi Bao (詩報) poetry publication noted that she “had deep beliefs in emancipation.” In a footnote, the author explained that “emancipation” referred to Tsai’s “determination to seek equal rights and freedom for women” and “to remain free of the shackles of men and superstitions.”

In addition to poetry, Tsai also developed an interest in painting, and Lin sponsored her in 1934 to travel to Xiamen to take classes. Studying abroad was something reserved for the elite, but Tsai was determined enough to find a way. Tsai remained active until about 1937 — around the time the colonial government started banning all things Chinese through the Kominka Movement (皇民化運動).

She returned to Penghu in 1955, only to find that part of Chengyuan Temple (澄源堂), where she taught her first students, was occupied by Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) troops and their families. She and her brother sued and obtained the rights to it in 1957, and Tsai ran the temple for a year until she died.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of