The National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts (Weiwuying)-Deutsche Oper am Rhein production of Giacomo Puccini’s Turandot premiered in Germany in December 2015, but its Taiwan premiere was delayed until last week due to Weiwuying not opening until October last year.

So great was the anticipation for the Taiwanese-helmed production that when tickets for the three performances went on sale late last year they sold out fast — even though Weiwuying’s Opera House has 2,236 seats. The theater added a fourth show, which also sold out.

Director Li Huan-hsiung (黎煥雄) and his creative team made several brave choices for this production that paid off, while the predominately Taiwanese cast on Friday night last week, led by Hanying Tso-Petanaj (左涵瀛) in the title role, were terrific.

Photo courtesy of the National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts

Li’s Turandot is a stunner, from stage designer Liang Jo-shan’s (梁若珊) minimalist set, to Lai Hsuan-wu’s (賴宣吾) costumes — which were all made by the Deutsche Oper am Rhein’s costume shop — to the projections of video designer Wang Jun-jieh (王俊傑).

I don’t think I have ever heard the Evergreen Symphony Orchestra (長榮交響樂團), conducted by Weiwuying artistic director Chien Wen-pin (簡文彬), and beefed up with musicians from the Kaohsiung City Wind Orchestra (高雄市管樂團), sound so good.

Some of Li’s choices were bound to be controversial, beginning with his decision to stage the opera as a dream, or actually more nightmare, of a modern Chinese woman — white-clad dancer Yu Cheng-jung (余承蓉) — who drifts in and out of the action and sometimes becomes a player.

Photo courtesy of the National Kaohsiung Center for the Arts

The opening scene behind a scrim evokes Hong Kong’s 2014 Umbrella protests: the chorus huddles under black umbrellas while black-clad helmeted riot police stand behind their shields along the ramparts of a silhouette of a Chinese walled city, with the message “Cease or we open fire” emblazoned over the archway.

Emperor Altoum was sung by Chang Yuh-yin (張玉胤), Timur by South Korean basso Taihwan Park, Calaf by Italian tenor Dario Di Vietri, Liu by Taiwanese soprano Lin Ling-hui (林玲慧), with Singaporean baritone Martin Ng (吳翰衛) as Ping, Taiwanese Amis tenor Claude Lin (林健吉) as Pang, Taiwanese-American tenor Joseph Hu (胡中良) as Pong and Taiwanese baritone Rios Li (李增銘) as the Mandarin.

Tso-Petanaj and Lin Ling-hui were just as stunning as they had been in the National Symphony Orchestra’s (NSO, 國立臺灣交響樂團) production of Puccini’s Il Trittico in July 2017.

Photo courtesy of Bare Feet Dance Theatre

While I was not initially impressed by Di Vietri, by the time Calaf’s famous aria Nessun Dorma rolled around in Act Three he had hit his stride.

I was also impressed by Ng, whose portrayal of Scarpia in the NSO’s concert version of Tosca in February at the National Concert Hall in Taipei was stiff. As Ping, the lord chancellor, he was much more animated, not to mention funny.

Lai’s costume were an interesting design mix, ranging from a mix of ethnicities in Yuan Dynasty China — Han, Muslims, Mongolians and Tibetans — to magnificent robes for Turandot. He dressed the emperor in a suit and bowler hat like Puccini used to wear, while Ping, Pang and Pong shifted between Yuan-like court robes and 19th century Western suits, much as the stage imagery shifted between ancient China and modern-day Asia.

However, the best thing about Weiwuying’s production of Turandot is that it will not disappear like a dream once the night is over, the way most of the major international shows coproduced by the National Theater have done.

Chien said Weiwuying is going to build a repertoire of works that it will perform regularly, starting with Turandot.

On Saturday night in the National Experimental Theater in Taipei, I was faced with the same conundrum as the previous weekend in main theater: How to reconcile a choreographer’s stated intention with what was presented on stage.

While Christian Rizzo’s une maison, performed by France’s International Choreographic Institute-CCN as part of the Taiwan International Festival of Arts, ended up being more than the sum of its parts and quite enjoyable, Bare Feet Dance Theatre’s (壞鞋子舞蹈劇場) An Eternity Before and After (渺生) began to feel more like an endless academic exercise of interest only to kinesiologists.

Artistic director and choreographer Lin I-chin’s (林宜瑾) idea was to have her dancers build and accumulate energy before it is depleted and weakens into the start of another cycle.

An Eternity Before and After turned out to be an endurance test for audience members, for dancers Panay Pan and Liu Chun-te (劉俊德), and for their simple white sleeveless shift dresses by designer Erichoalic (蔡浩天).

It was also a race against time to see which would collapse first: the two dancers, who were pushing their bodies to the limits in a 50-minute work where they basically never stopped moving or their costumes, which, as they became plastered by sweat to the pair’s torsos and legs, began to break apart and dissolve.

The piece begins with new media artist Chuang Chih-wei’s (莊志維) installation work: nine interconnected silver rods of differing lengths, clinking on the floor in the darkness as they were tugged by lines running from the grid loft overhead.

As the rods were pulled toward the ceiling, Pan and Liu appeared as dim ghostly shapes in the dark, swaying almost imperceptibly in place in the center. As the lighting brightened, their movements slowly became more pronounced, rocking gently, arms swinging back and forth, the minimalist moves becoming more rhythmic, more expansive, only to start contracting and declining, again and again and again to an electro-tech soundtrack by Lee Tzu-mei (李慈湄).

The pair’s movements were interdependent, yet they moved independently for most of the show, their efforts completely internalized. When they did start to touch, they were not so much joining together as clinging on for support.

Just when you think they could not possibly have any energy left, they began to move in even more exaggerated motions and at a faster pace, as Chuang’s rods spun and dipped over their heads.

One has to admire the dancers’ commitment and stamina, and Liu’s effort to get her audiences to appreciate motion for its own sake, but An Eternity Before and After is a challenge to watch, and makes little effort to connect with its audiences.

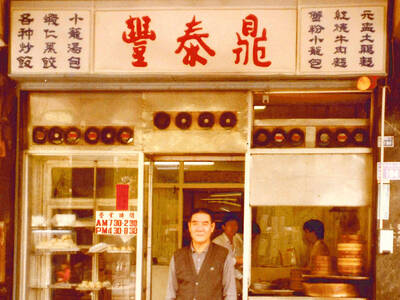

March 24 to March 30 When Yang Bing-yi (楊秉彝) needed a name for his new cooking oil shop in 1958, he first thought of honoring his previous employer, Heng Tai Fung (恆泰豐). The owner, Wang Yi-fu (王伊夫), had taken care of him over the previous 10 years, shortly after the native of Shanxi Province arrived in Taiwan in 1948 as a penniless 21 year old. His oil supplier was called Din Mei (鼎美), so he simply combined the names. Over the next decade, Yang and his wife Lai Pen-mei (賴盆妹) built up a booming business delivering oil to shops and

Indigenous Truku doctor Yuci (Bokeh Kosang), who resents his father for forcing him to learn their traditional way of life, clashes head to head in this film with his younger brother Siring (Umin Boya), who just wants to live off the land like his ancestors did. Hunter Brothers (獵人兄弟) opens with Yuci as the man of the hour as the village celebrates him getting into medical school, but then his father (Nolay Piho) wakes the brothers up in the middle of the night to go hunting. Siring is eager, but Yuci isn’t. Their mother (Ibix Buyang) begs her husband to let

The Taipei Times last week reported that the Control Yuan said it had been “left with no choice” but to ask the Constitutional Court to rule on the constitutionality of the central government budget, which left it without a budget. Lost in the outrage over the cuts to defense and to the Constitutional Court were the cuts to the Control Yuan, whose operating budget was slashed by 96 percent. It is unable even to pay its utility bills, and in the press conference it convened on the issue, said that its department directors were paying out of pocket for gasoline

On March 13 President William Lai (賴清德) gave a national security speech noting the 20th year since the passing of China’s Anti-Secession Law (反分裂國家法) in March 2005 that laid the legal groundwork for an invasion of Taiwan. That law, and other subsequent ones, are merely political theater created by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) to have something to point to so they can claim “we have to do it, it is the law.” The president’s speech was somber and said: “By its actions, China already satisfies the definition of a ‘foreign hostile force’ as provided in the Anti-Infiltration Act, which unlike