Very little is known about Taiwan’s early history prior to the arrival of European explorers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Taiwan’s Aboriginal population of Malay-Polynesian descent, had been here for millennia, interacting with other peoples in the region.

The most fascinating aspect of this interaction is that, based on linguistic and DNA studies, it has been determined that the people in the wider Pacific originated in Taiwan. From around 3,500 BC, sailors from Taiwan set out on simple rafts and outrigger canoes, and island-hopped — from the Philippines, through Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia, eventually reaching far-away places such as New Zealand and Madagascar.

But what about those coming to Taiwan? Records of successive Chinese empires show scant mention of the island and its people. And if there is a mention, it is sometimes not even certain whether it was a reference to an encounter with Aborigines in Taiwan or with those in Okinawa. During the 13th century there were the Kublai Khan expeditions against Japan (1281-91) and the voyages by Admiral Zheng He (鄭和) under Ming emperor Yung Lo (永樂, 1405-1433), reaching all the way to the African coast, but there are no records of either of these reaching Taiwan.

Photo: CNA

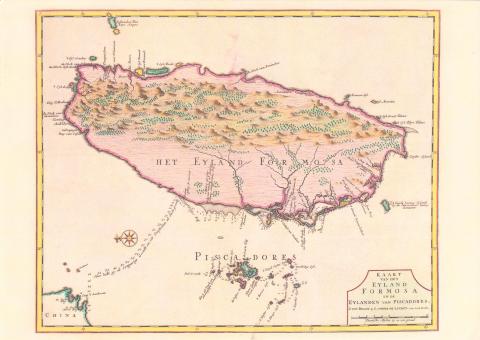

So how did Taiwan, which came to be known as Ilha Formosa, end up so prominently on world maps in the 17th Century?

THE RENAISSANCE AND ‘THE ORIENT’

The mid fifteenth century saw the birth in Europe of the Renaissance. After the relatively inward-looking Middle Ages, a major revival in the arts, architecture and sciences flourished around Florence, and quickly spread throughout Europe.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The continent started to be much more outward-looking, commerce and trade grew exponentially and technical discoveries such as the compass led to the search for, discovery and exploration of new continents. The realization set in that the Earth was not flat, and that there were far-away continents to explore.

Prime among these was “The Orient.” At the end of the thirteenth century (1271-1295) Marco Polo from the city state of Venice, made his overland journey to China and southeast Asia, returning home with incredible tales.

Portuguese explorers first traveled south in 1497, with Vasco da Gama (1460-1524) making three trips around the Cape of Good Hope to India, where he established the two major colonies, Goa and Cochin. In 1519, Ferdinand de Magelhaens (1480-1521) also headed south, but turned around Cape Horn, crossing the Pacific to what is now the Philippines. He died in a fight with local warriors, but his men continued home, becoming the first to circumnavigate the globe.

Earlier, two Italian explorers in the service of the King of Spain also made an attempt to find what became known as the East Indies. From 1492 through 1503 Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) made four voyages, and instead of finding the East Indies, discovered the West Indies. During the same period, his countryman Amerigo Vespucci (1454-1512) made three voyages, discovering a continent further south, and naming it after himself: America.

In the end both Spain and Portugal carved niches out for themselves in the lucrative trade in spices, silk and china with the East. Portugal established its conclaves in India, the Spice Islands and Macao, while Spain carved out a major trade route to the East via Central America — from Spain to coastal cities on Mexico’s southeast coast, overland to Acapulco and across the Pacific to Manila.

In fact, it was Portuguese sailors who, in 1544, first passed by Taiwan on their way to Japan, dubbing it Ilha Formosa, a moniker that would stick in the West until the early 1950s. But there are no records of the Portuguese landing and establishing a foothold here.

In 1571, Manila was established as the headquarters of the Spanish East Indies by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi (1502-1572), becoming a lively post for trading with the Chinese coast and the Spice Islands, in what is now Indonesia.

THE ARRIVAL OF THE DUTCH

However, Spain and Portugal’s trade dominance in the region didn’t last. In the late 16th Century a new power emerged: the Dutch. Actually, during much of that time, the Dutch were fighting for their independence from Spain.

By the end of the 16th Century, the Dutch had already been a seafaring nation for several centuries, mainly plying the waters of the Baltic and Mediterranean, and had thus built up experience with navigation and mapmaking. But at that point, they also made some significant technological breakthroughs in shipbuilding, using windmill power to cut wood for shipbuilding.

Around 1594-95, the Dutch wanted to find their own way to the East. The route around the Cape of Good Hope was dominated by the Portuguese and, via Central America, by Spain. So, they started to look for the Northeast Passage (north of Russia) and Northwest Passage (north of what is now Canada).

The most significant contribution to the discovery of the Orient was made by Jan Huygen van Linschoten (1563-1611), who as a young clerk at the age of 20 entered into the service of the Portuguese bishop of Goa in 1583. In this position he was able to collect much information on the Portuguese trade routes, which were considered highly confidential trade secrets by the Portugal.

But in 1592 he was able to return to The Netherlands, and started to write a book about his Portuguese adventures, in the process describing the trade routes in detail. The book, Itinerario: Voyage ofte schipvaert van Jan Huyghen van Linschoten naer Oost ofte Portugaels Indien (1579-1592), was published in 1596.

EXPANDING TRADE

The book was an immediate success, and in the subsequent years, hundreds of Dutch ships ventured out in search of the Orient. The situation got so chaotic that in 1602 the Dutch authorities prohibited individual ships from sailing out, allowing only fleets authorized by the newly-established Dutch East India Company to make the long journey via the Cape of Good Hope.

In the next two decades, the Dutch East India Company aggressively expanded its foothold in East Asia, in 1619 establishing its headquarters in Batavia, present-day Jakarta, establishing dozens of trading posts along the coastlines stretching from India to the Spice Islands.

By 1622, the Dutch expanded trade to the Chinese coast, and attempted to take the Portuguese stronghold of Macao. However, they were beaten back, which resulted in them establishing a fortress on the Pescadores, an island chain off the west coast of Taiwan that is also called Penghu, from where they conducted trade with the Chinese coast. At the same time, the Dutch tried to inhibit shipping by Spanish and Portuguese competitors (see “A Swiss soldier on Dutch Formosa,” Taipei Times, Oct. 4, 2018, p14).

However, in early 1624, Ming Dynasty emperor Zhu Youxiao (朱由校) sent an envoy and an imposing war fleet to the region and ordered the Dutch to leave the Pescadores and move “beyond Chinese territory.” The Dutch had previously found a sandy bank on the southwest coast of Formosa, building a small fortress there.

Thus at the end of August 1624, the Dutch tore down their fortress on the Pescadores and started to lay the foundations for what was to become Fort Zeelandia, in present-day Tainan. This was the beginning of 38 years of Dutch colonial rule, during which the harbor of Tayouan — Anping District (安平) in present-day Tainan — would become a major and prosperous international trading post, linking Taiwan to Japan, southeast Asia and as far as India and Persia. Taiwan was put on the world map and “connected to the world” in that first phase of globalization.

— Gerrit van der Wees is a former Dutch diplomat. From 1980 through 2016 he also served as editor of Taiwan Communique, a publication chronicling Taiwan’s momentous transition to democracy. He presently teaches history of Taiwan at George Mason University.

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

Ten years ago, English National Ballet (ENB) premiered Akram Khan’s reimagining of Giselle. It quickly became recognized as a 21st-century masterpiece. Next month, local audiences get their chance to experience it when the company embark on a three-week tour of Taiwan. Former ENB artistic director Tamara Rojo, who commissioned the ballet, believes firmly that if ballet is to remain alive, works have to be revisited and made relevant to audiences of today. Even so, Khan was a bold choice of choreographer. While one of Britain’s foremost choreographers, he had never previously tackled a reimagining of a classical ballet, so Giselle was