Jan. 21 to Jan. 27

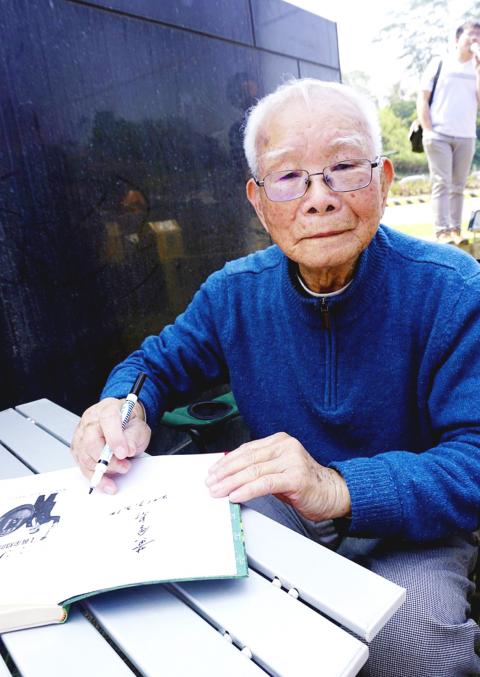

Although he died peacefully last Tuesday, the press referred to him as the “eternal warrior” in their obituaries. The Liberty Times (the sister newspaper of the Taipei Times) probably offered the most impressive moniker for him in its report: “The 228 warrior who resisted repression and knew no fear throughout his life (一生不知怕是什麼228抗暴戰士).”

Joining the Japanese Army in 1942 at age 16, Huang Chin-tao (黃金島) would not know peace until 1975, because he was fighting, on the run or in jail. And the adventures continued upon his release as he and his wife, Wang Chao-e (王昭娥), became involved in Taiwan’s budding democracy movement, later investigating the truth of the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was brutally suppressed, and advocating for the rights of fellow Taiwanese who served in the Japanese Army.

Photo courtesy of 27th Brigade Documentary

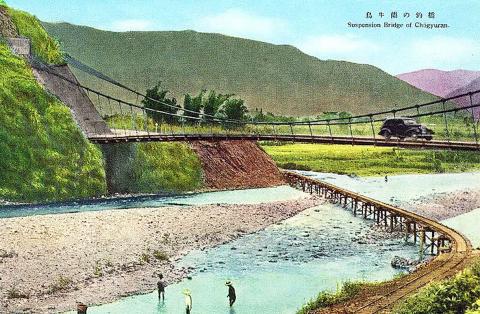

Huang is probably best known for his role as frontline commander during the Battle of Wuniulan (烏牛欄) in Nantou near the end of the 228 Incident, where he and a band of about 30 student guerrillas for the 27th Brigade clashed with the government forces on March 16, 1947, holding out until they ran out of ammunition and disbanded.

Anything related to the 228 Incident was taboo for the next four decades, but fortunately, Huang lived long enough to see this piece of history come to light. A monument to the battle was erected in Nantou in 2004 and another in Taichung in 2017 honoring the 27th Brigade. His exploits are also featured in heavy metal band Chthonic’s song The Guardian of Wuniulan (烏牛欄大護法), as well as the 2017 production The 27 Brigade Documentary (2七部隊紀錄片).

JAPANESE SOLDIER

Taipei Times file photo

Huang was born Huang Tsuen-tao (黃圳島) to a middle-class farming family in Taichung, later changing his name after he was wanted for his role in the Wuniulan battle. He headed to Japan to study medicine in 1941, but Japan was gearing up for World War II and he ended up joining the Imperial Japanese Navy’s transportation division.

Huang writes that he officially joined the Japanese Army for one reason: he resented the fact that the Japanese discriminated against Taiwanese and wanted to prove that he could serve like a Japanese. It was a difficult process with a one out of six chance of being admitted.

He first saw action after a few days at sea when he was sent to help rescue the crew of nearby ship hit by a torpedo. However, his lifeboat flipped over, and he had to wait to be saved as well.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

A month after arriving on China’s Hainan Island, the Americans bombed the Japanese base where Huang was stationed. He survived, but recalls in his memoir seeing shrapnel and body parts scattered everywhere. Many Taiwanese died in the raid, he writes.

During one mission, Huang managed to stop his Japanese comrades from firing on innocent Chinese civilians. Half a century later, he would still mention this exploit while criticizing the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) army for killing civilians during the 228 Incident.

Like most Taiwanese, he was also overjoyed to return to the “motherland” after Japanese defeat. But instead, the KMT rounded up the Taiwanese soldiers and their families and placed them into camps around Hainan, where sickness was common and food was scarce. While the Japanese soldiers were sent home by the end of 1945, the Taiwanese remained in the camps for another year.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Fed up with the situation, Huang escaped and set up a small shop in Haikou, the provincial capital of Hainan. Business was good, but all he wanted was to return to Taiwan to get help for those still in the camp. After bribing local officials and forging documents, he and a group of Taiwanese set out in May 1946. The crew survived severe storms, but were robbed and kidnapped by pirates. They finally landed in Chiayi a month later, their adventure and the plight of the Taiwanese in Hainan making the national press.

A DOOMED BATTLE

Eight months later, the 228 Incident broke out. The violence spread from Taipei to Huang’s hometown by March 1, 1947, and after watching government troops indiscriminately shot civilians in front of the Taichung Hotel (台中大飯店), Huang decided to join the resistance.

Noted Taiwanese communist Hsieh Hsueh-hung (謝雪紅) was the main resistance leader in Taichung. As the only one in the ragtag Independent Security Brigade (獨立治安隊) with military experience, Huang had to teach his comrades basic skills such as standing guard and using weapons. The group was merged with others to form the 27th Brigade on March 6, with Huang’s serving as head of its security unit.

KMT reinforcements soon arrived from China and started to push their way south. Huang suggested retreating to Nantou County’s Puli area and resisting with guerrilla tactics due to the small size of their forces and to avoid harming civilians. The group stood by in the local Butokuden, or Martial Arts Hall (武德殿), and by March 13, the government troops had reached Taichung.

Huang recalls meeting Hsieh several times, noting that she had a calming effect on the brigade, who faced a doomed battle.

“The troops were growing restless, but once they saw that Hsieh, as a woman, was determined to fight to the end, they changed their mind because they didn’t want to appear inferior to a woman,” he writes.

The first mission was a raid on the KMT camp at Sun Moon Lake, where about 100 fighters drove away the enemy and looted their fresh supplies. The official battle began in the wee hours of March 16, as at least 700 government troops marched into Puli. Hiding above in the mountains, Huang launched the first attack, bombarding the unsuspecting enemy with grenades. He writes that the KMT troops were hesitant since they were unsure of the enemy’s numbers, and that they could have easily wiped out the brigade if they attacked with full force. But the troops held out for an entire day before deciding to disband after Huang learned that the KMT had captured the brigade’s headquarters at the Butokuden and most of the leaders had fled.

Huang writes that they inflicted great losses on the KMT troops, and although they ultimately failed, they gave their all for freedom and their homeland.

LIFE SENTENCE AND RELEASE

Huang now began his life on the run. He first pretended to be his brother and found work at a tire factory. The greatest irony of his life, he writes, happened next when he changed his name and joined the Republic of China Marine Corps.

“The most dangerous place is also the safest,” Huang writes.

Still believing that it was safest to remain in the military, Huang later joined the Armor Training Command. He was arrested and questioned several times during this period, but he talked his way out every time. However, on June 1, 1952, Huang was abruptly jailed. He was sentenced to life, but was released in 1975 after the death of former president Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石).

“I saw all of these setbacks as challenges from God, and I triumphed in the end,” he writes.

Huang had many opportunities to get married while he was in Haikou, but he only wanted to return to Taiwan. After he got out of jail, he married Wang, and the couple spent their days organizing or participating in pro-democracy protests around the nation. Huang was a founding member of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), but he writes that he quit politics to focus on bringing 228 Incident history to light.

“My wife and I call ourselves ‘democracy farmers,’” he writes. “We just wanted to sow the seeds of democracy and let it take root. We don’t want any undeserved credit.”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.