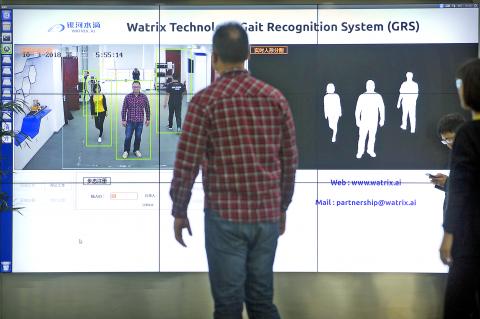

Chinese authorities have begun deploying a new surveillance tool: “gait recognition” software that uses people’s body shapes and how they walk to identify them, even when their faces are hidden from cameras.

Already used by police on the streets of Beijing and Shanghai, “gait recognition” is part of a push across China to develop artificial-intelligence and data-driven surveillance that is raising concern about how far the technology will go.

Huang Yongzhen (黃永禎), the CEO of Watrix, said that its system can identify people from up to 50 meters away, even with their back turned or face covered. This can fill a gap in facial recognition, which needs close-up, high-resolution images of a person’s face to work.

Photo: AP

“You don’t need people’s cooperation for us to be able to recognize their identity,” Huang said in an interview in his Beijing office. “Gait analysis can’t be fooled by simply limping, walking with splayed feet or hunching over, because we’re analyzing all the features of an entire body.”

Watrix announced last month that it had raised 100 million yuan (US$14.5 million) to accelerate the development and sale of its gait recognition technology, according to Chinese media reports.

Chinese police are using facial recognition to identify people in crowds and nab jaywalkers, and are developing an integrated national system of surveillance camera data. Not everyone is comfortable with gait recognition’s use.

Photo: AP

Security officials in China’s far-western province of Xinjiang, a region whose Muslim population is already subject to intense surveillance and control, have expressed interest in the software.

SOCIAL CONTROL

Shi Shusi, a Chinese columnist and commentator, says it’s unsurprising that the technology is catching on in China faster than the rest of the world because of Beijing’s emphasis on social control.

“Using biometric recognition to maintain social stability and manage society is an unstoppable trend,” he said. “It’s great business.”

The technology isn’t new. Scientists in Japan, the UK and the US Defense Information Systems Agency have been researching gait recognition for over a decade, trying different ways to overcome skepticism that people could be recognized by the way they walk.

Professors from Osaka University have worked with Japan’s National Police Agency to use gait recognition software on a pilot basis since 2013.

But few have tried to commercialize gait recognition. Israel-based FST Biometrics shut down earlier this year amid company infighting after encountering technical difficulties with its products, according to former advisory board member Gabriel Tal.

COMPLEX BIOMETRICS

“It’s more complex than other biometrics, computationally,” said Mark Nixon, a leading expert on gait recognition at the University of Southampton in Britain. “It takes bigger computers to do gait because you need a sequence of images rather than a single image.”

Watrix’s software extracts a person’s silhouette from video and analyzes the silhouette’s movement to create a model of the way the person walks. It isn’t capable of identifying people in real-time yet. Users must upload video into the program, which takes about 10 minutes to search through an hour of video. It doesn’t require special cameras — the software can use footage from surveillance cameras to analyze gait.

Huang, a former researcher, said he left academia to co-found Watrix in 2016 after seeing how promising the technology had become. The company was incubated by the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Though the software isn’t as good as facial recognition, Huang said its 94 percent accuracy rate is good enough for commercial use.

He envisions gait recognition being used alongside face-scanning software.

Beyond surveillance, Huang says gait recognition can also be used to spot people in distress such as elderly individuals who have fallen down. Nixon believes that the technology can make life safer and more convenient.

“People still don’t recognize they can be recognized by their gait, whereas everybody knows you can be recognized by your face,” Nixon said. “We believe you are totally unique in the way you walk.”

— Additional reporting by Olivia Zhang

Nov. 11 to Nov. 17 People may call Taipei a “living hell for pedestrians,” but back in the 1960s and 1970s, citizens were even discouraged from crossing major roads on foot. And there weren’t crosswalks or pedestrian signals at busy intersections. A 1978 editorial in the China Times (中國時報) reflected the government’s car-centric attitude: “Pedestrians too often risk their lives to compete with vehicles over road use instead of using an overpass. If they get hit by a car, who can they blame?” Taipei’s car traffic was growing exponentially during the 1960s, and along with it the frequency of accidents. The policy

What first caught my eye when I entered the 921 Earthquake Museum was a yellow band running at an angle across the floor toward a pile of exposed soil. This marks the line where, in the early morning hours of Sept. 21, 1999, a massive magnitude 7.3 earthquake raised the earth over two meters along one side of the Chelungpu Fault (車籠埔斷層). The museum’s first gallery, named after this fault, takes visitors on a journey along its length, from the spot right in front of them, where the uplift is visible in the exposed soil, all the way to the farthest

While Americans face the upcoming second Donald Trump presidency with bright optimism/existential dread in Taiwan there are also varying opinions on what the impact will be here. Regardless of what one thinks of Trump personally and his first administration, US-Taiwan relations blossomed. Relative to the previous Obama administration, arms sales rocketed from US$14 billion during Obama’s eight years to US$18 billion in four years under Trump. High-profile visits by administration officials, bipartisan Congressional delegations, more and higher-level government-to-government direct contacts were all increased under Trump, setting the stage and example for the Biden administration to follow. However, Trump administration secretary

The room glows vibrant pink, the floor flooded with hundreds of tiny pink marbles. As I approach the two chairs and a plush baroque sofa of matching fuchsia, what at first appears to be a scene of domestic bliss reveals itself to be anything but as gnarled metal nails and sharp spikes protrude from the cushions. An eerie cutout of a woman recoils into the armrest. This mixed-media installation captures generations of female anguish in Yun Suknam’s native South Korea, reflecting her observations and lived experience of the subjugated and serviceable housewife. The marbles are the mother’s sweat and tears,