Submarine crews in wartime generally know the date and time, but often lose track of the days. And the nights. On Tuesday May 29, 1945, just a few minutes past zero-hundred hours, the USS Bluegill, a Gato-class American submarine, burst up through ghostly phosphorescent waves and into the glistening full-moonlit sea about three miles southwest of Pratas atoll in the South China Sea.

Within minutes, the topside hatches swung open. Emerging crewmen hoisted boxes of ammo, firearms, radio sets and life vests on deck. They assembled folding “fol-boats” and a large rubber equipment boat under the eye of two Australian commando officers assigned to the sub. When all was ready, the commandos boarded a fol-boat alongside in the sea froth, then loaded the gear, explosives and automatic weapons. With their oars, the commandos pushed off from the sub’s steel hull, paddled easily and quietly toward the dimly visible white beaches on a 70-minute trip to low-lying Pratas Island (東沙), also known as Tungsha Island.

When the rubber boat swept with gentle breakers onto the nighttime sands, the two men leaped into the foam and dragged it into the beach’s scrub fringe. They listened for any hint of a Japanese garrison. Nothing. Shouldering their weapons, they scouted up the underbrush margins to discover trenches, foxholes, remains of recent campfires — but no humans.

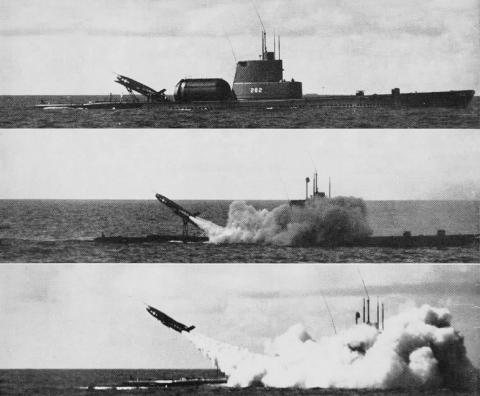

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Another several hundred yards on, they confronted the nighttime shadows of two large wooden cannons guarded ostentatiously by two motionless figures in Japanese navy uniforms.

“We watched and waited for what seemed forever but was probably no more than five minutes,” one of the commandos later recalled; the guards were not fierce Japanese kaigun rikusentai, the Japanese Special Naval Landing Forces, but straw-stuffed scarecrows, armed with wooden sticks, immovable sentries for makeshift lumber howitzers.

In a methodical four-hour night reconnaissance, they crisscrossed the abandoned palm-forested island, its Japanese radio-weather station, the concrete jetty and barracks buildings, from end to end. On the north side of the encampment charcoal ash, fresh fruit and still-thriving flowers in a small Shinto shrine told the Australians that the island had been abandoned perhaps 10 days earlier. Confident that the island was safe, the Australians returned to the beach and radioed their mother-ship. The Bluegill’s commander, with the all-clear from the shore party, signaled from the conning tower for the 10-man team on deck to load their landing boats and make for the beach.

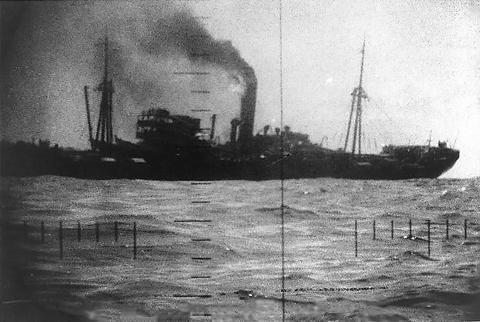

Photo courtesy of John J Tkacik, Jr

Once on the Pratas, the 12 invaders fanned out through the encampment and pier areas to document the island’s topography, facilities and supply stockpiles.

The submarine log reads: “We assembled around the flag pole, and at 1022 on May 29, 1945, a handful of soldiers and sailors stood at solemn attention while the Stars and Stripes slowly ascended the flag pole and two captured Jap bugles blared forth. The land they now stood on was US territory! A plaque was then affixed to the base of the pole certifying the capture of the island by the crew of the USS Bluegill.”

Sadly, if the Pratas atoll was “US territory,” its new owners lavished it with neither the dignity nor tender care due sovereign property. The Americans departed on May 29 as quickly as they arrived, carting off canned Japanese vegetables, war souvenirs, neglected codebooks and any naval documents left unburnt. The Australian commandos set explosive charges to the rest of it. The Pratas was a dismal pall of smoke as the Bluegill set sail at 4:40pm that afternoon.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

WITNESS TO WAR ON FORMOSAN SHORES

Two days later, the Bluegill entered a “newly assigned area for life guard duty [southwest] of Takao [today’s Kaohsiung],” where the war there, daily and mercilessly, still raged.

“Witnessed airstrike over Takao. Air literally filled with friendly aircraft of all types. Our aircover has long since deserted us.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

At one point, the Bluegill raced at top speed to “recover eight aviators in the water some 60 miles up from coast just off the beach [and] … forced to enter unknown mine fields in attempting to effect their rescue.”

On its route, the Bluegill was pressed under the waves by a rapidly closing Japanese seaplane bomber. At six o’clock that first evening, another Japanese dive bomber caught the Bluegill in shallow water.

“Received one bomb. Surprised we weren’t overwhelmed we were so close to beach. Our position inside harbor buoys of Toshien harbor (左營軍港).”

To the Bluegill’s dismay, once she arrived at the reported coordinates for the rescue of the downed-aviators, “No aviators nor raft nor friendly aircraft in sight.”

A third Japanese dive bomber sighted the sub and loosed a charge, and an hour later, a fourth Japanese aircraft dropped two bombs. By nightfall, the Bluegill logbook lamented that “The cooperation of friendly aircraft this date was remarkable by its absence.”

At sunup on June 1, the Bluegill had more than enough air cover.

“The sky was black with friendly aircraft of all types through most of the day.”

The sub watch team recorded American PBY amphibious aircraft, B-24 and B-25 heavy bombers, the latest and most modern P-38 and P-51 fighters, huge PB-2Y seaplane bombers, and the long-range workhorse B-17 bombers.

“Quite an impressive and soul-satisfying sight,” reads the submarine’s log.

“Soul-satisfying” perhaps to the officers and crew of the Bluegill, but hellish nightmares to myriads of those living on Taiwan in target cities ashore who endured that late spring monsoon of white hot steel and shrapnel.

And the bombing went on. All day on June 2, “The sky was again filled with own aircraft of all descriptions. Golly, but we’re proud to be Americans.” On June 3, “The usual large number of friendly planes were overhead throughout the day.”

Happily, no new calls for downed pilot rescues came in the ensuing days. The relentless bombing quickly destroyed all coastal defenses on Formosa. After a week, witness to the distant eruptions and curtains of carpet bombing from well offshore, on June 6, the Bluegill handed off lifeguard tasks to another submarine and headed southeast again, past the Pratas Reef (their newly renamed “Bluegill Island”) and skirting farther to the east of the marooned and beleaguered Japanese garrison holding out on the Philippine island of Batan. Its destination was Saipan for replenishment and resupply.

On July 2, 1945, the Commander of Submarine Force Pacific formally reported to Naval headquarters in Washington DC that “in a fitting ceremony on 29 May 1945 the Bluegill raised the national ensign on Pratas Island and proclaimed it ‘Bluegill Island.’”

Commodore Merrill Comstock, proudly informed the Pentagon that the USS Bluegill, one of his 465-boat submarine fleet’s 20 top submarines, had been awarded a new combat insignia for the mission, and indeed the Bluegill’s “Sixth Combat Mission” battleflag shows five Japanese warships and nine merchant ships sunk, and one tropical island captured.

Seven decades later, it is tempting for military and naval historians to rue missed opportunities, especially given the unforeseen prominence of the hundreds of atolls, islets, reefs and sandbars of the South China Sea. Pratas Island, occupied for a single day in 1945 by a handful of American sailors, was a mere footnote-of-a-footnote in the military-industrial holocaust that was the War in the Pacific, a war in which the US was the principal victor and the sole occupying power of defeated Japan. Today, by everyone’s common agreement, it belongs to a republic of China, but which one? And so, now, it is simple fun to imagine what the 21st century controversies in the South China Sea would have been like if Pratas had remained “US territory” for more than one day in 1945.

John J. Tkacik, Jr. is a retired US foreign service officer who has served in Taipei and Beijing and is now director of the Future Asia Project at the International Assessment and Strategy Center.

In recent weeks the Trump Administration has been demanding that Taiwan transfer half of its chip manufacturing to the US. In an interview with NewsNation, US Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick said that the US would need 50 percent of domestic chip production to protect Taiwan. He stated, discussing Taiwan’s chip production: “My argument to them was, well, if you have 95 percent, how am I gonna get it to protect you? You’re going to put it on a plane? You’re going to put it on a boat?” The stench of the Trump Administration’s mafia-style notions of “protection” was strong

Every now and then, it’s nice to just point somewhere on a map and head out with no plan. In Taiwan, where convenience reigns, food options are plentiful and people are generally friendly and helpful, this type of trip is that much easier to pull off. One day last November, a spur-of-the-moment day hike in the hills of Chiayi County turned into a surprisingly memorable experience that impressed on me once again how fortunate we all are to call this island home. The scenery I walked through that day — a mix of forest and farms reaching up into the clouds

With one week left until election day, the drama is high in the race for the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) chair. The race is still potentially wide open between the three frontrunners. The most accurate poll is done by Apollo Survey & Research Co (艾普羅民調公司), which was conducted a week and a half ago with two-thirds of the respondents party members, who are the only ones eligible to vote. For details on the candidates, check the Oct. 4 edition of this column, “A look at the KMT chair candidates” on page 12. The popular frontrunner was 56-year-old Cheng Li-wun (鄭麗文)

Oct. 13 to Oct. 19 When ordered to resign from her teaching position in June 1928 due to her husband’s anti-colonial activities, Lin Shih-hao (林氏好) refused to back down. The next day, she still showed up at Tainan Second Preschool, where she was warned that she would be fired if she didn’t comply. Lin continued to ignore the orders and was eventually let go without severance — even losing her pay for that month. Rather than despairing, she found a non-government job and even joined her husband Lu Ping-ting’s (盧丙丁) non-violent resistance and labor rights movements. When the government’s 1931 crackdown