The Swiss in the 17 century were known as Europe’s foreign legionnaires: in the many conflicts and wars within Europe, one was bound to find Swiss regiments that fought for the highest bidder. The current Swiss Guard at the Vatican still reminds us of those days.

At the time, Switzerland consisted of a number of poor land-locked cantons, with very little economic activity, so young Swiss men traveled to other countries in search of a livelihood and adventure, selling their military prowess.

One of those men was Elie Ripon, a French-speaking Swiss soldier from Lausanne, who in 1617 traveled to the Netherlands to try his luck. He initially served on a whaling expedition to Greenland, but took a serious dislike to the activity, so the next year he signed up with the Dutch East India Company, and was sent to the Far East.

Ripon wrote a diary in French, which collected dust in an attic for a couple of centuries until 1865, when the manuscript was discovered in an old home in Bulle, in the Swiss canton of Gruyere. In the 1980s the researcher Yves Giroud published the French manuscript, while the Dutch version, on which this review is based, was published in 2016 by Leonard Blusse of Leiden University and Jaap de Moor.

THE DUTCH IN BATAVIA

In his diary, Ripon gives a colorful description of the trip from The Netherlands via Cape of Good Hope to Batavia (present day Jakarta, Indonesia), which lasted about half a year. There he is immediately engulfed in the fighting between the Dutch — who in 1619 had just built a small fortress near the entrance of the harbor — and the British, who together with the local Javanese sultan try to push the Dutch out.

The siege of the small fortress lasts some four months, but then Dutch governor-general Jan Pietersz Coen returns with reinforcements from the Moluccas, and with a large contingent of soldiers is able to defeat the British and the Javanese. Ripon is quickly promoted and is soon a captain in the army of the East India Company.

After the pacification of the area around Batavia, Ripon is sent to various locations in the Moluccas as well as to the islands to the East of Bali. He describes the local population and its customs, as well as exotic plants and animals.

RIPON ON TAIWAN

For Taiwan, the most interesting part of the diary is the period 1622 to 1624, when Ripon is sent to the Chinese coast with a fleet of 12 ships under Commander Cornelis Reijersen. The purpose of the trip is to establish a trading presence there.

And if taking Macau is not successful, they are to establish a fortress on Penghu to trade with the Chinese coast from there, and at the same time inhibit the trading operations of both the Spanish, who had established themselves in Manila in 1571, and the Portuguese, who had established a stronghold in Macau in 1557.

The Portuguese had been the earliest Western explorers and traders in the East Indies, but in the late 1500s they were gradually overshadowed by Spain. However, in the early 1600s, the Netherlands — which was fighting its own war of independence against Spain (1568-1648) — came up as a major trading power, and fought the Spanish and Portuguese wherever they could.

The arrival of the Dutch fleet off Macau doesn’t end peacefully: the Dutch land, and attempt to push out the Portuguese, but the attack is unsuccessful, and the Dutch have to retreat: Ripon gives a lively description of the fighting that took place. He himself just barely escapes.

At the time, Macau hosted about 2,000 Portuguese, 20,000 Chinese and around 5,000 African slaves, brought by the Portuguese from their colonies in Angola and Mozambique. It was actually mostly the Africans who fought off the Dutch assault; a Dutch officer reported that “[o]ur people saw very few Portuguese” during the battle.

The defeat at Macau necessitates the Dutch plan B: The remaining ships and troops sail to Penghu, where they arrive on July 5, 1622. There they start to build a simple fortress, and even disassemble one of the Dutch ships in order to have wood and other material to build the buildings: the island is so bare that there were no trees that could be used for this purpose.

In December 1622 the fortress is finished, and the remaining Dutch ships sail to both the Chinese coast for trade, and to Manila in order to block Spanish and Chinese ships from entering the harbor. Ripon sails on a ship to the coast, but found that the Chinese had little inkling to trade with the Dutch.

After about a year of skirmishes back and forth between the Dutch, the Chinese and the Spanish, the Ming Dynasty authorities along the Fujian coast decide that they want to push out the Dutch: in early 1624 they land a large force of some 10,000 soldiers on the North side of the island, and start to threaten the small Dutch fortress.

THE DUTCH AND ABORIGINES

It never came to real fighting: through the intermediary services of a disgraced former Ming official who had made his name in piracy, Li Tan (李旦, “Captain China”), the Dutch and the Chinese authorities come to an agreement that the Dutch will vacate the Penghu Fortress, and move “beyond Chinese territory.” In August 1624 the Dutch moved to a sandy beach at Tayouan, present-day Anping District (安平) in Tainan.

The interesting thing is that Ripon’s diary tells us that more than a year earlier, the Dutch had already set foot on Formosa: in October 1623, when the Dutch were still firmly established at Penghu, Ripon was sent out to Tayouan to build a small fortress there. He was thus one of the first Western observers to visit Aboriginal villages in the area.

He and his men first befriend the people of Bacaloan — present-day Anting District (安定) in Tainan — giving them small presents. He visits several of the surrounding villages, and describes the people, their customs, clothing, homes and daily activities. He also describes the headhunting, which went on from the time the harvest was in until the next planting season.

Interestingly, his friendship with the people of Bacaloan has a negative effect on the people of neighboring Mattau: they are jealous that they didn’t receive the same presents, and attack Ripon and his soldiers. The animosity with “the giants of Mattau” (these Aborigines were apparently quite tall) would last another decade until the pacification of the area in 1635.

Between October 1623 and March 1624, the small fortress, named Fort Oranje, withstands a couple of bad earthquakes, a typhoon, and a major attack by Mattau. However, at the end of March, the higher-ups decide to concentrate all Dutch forces at the Penghu Fortress, and Ripon is told to demolish the fortress at Tayouan and return to Penghu with his men.

However, only a few months later, when the Ming Emperor’s emissary tells the Dutch to “move beyond Chinese territory,” the Dutch return to Tayouan and establish a more permanent presence there. The agreement was signed on Aug. 24, 1624, and only four days later, the new governor, Martinus Sonck, leaves for Formosa to build a new fortress there. He arrives on Aug. 31, 1624, and immediately starts with the construction of what was to become Fort Zeelandia.

Ripon stays behind to oversee the dismantling of the Penghu Fortress, which is completed in just five days, from Sept. 8 through Sept. 13, 1624. He and his soldiers leave Penghu on Sept. 16 “with flying banners and the sounding of the drums,” arriving in Formosa a couple of days later.

There the construction of the new fortress has already started, so Ripon and his soldiers are tasked with finding food for the quickly expanding population. He goes hunting, and carries back some hares, pheasants and deer.

However, Ripon’s further stay at Formosa is short-lived: he strongly disagrees with the way the new governor, Cornelius Sonck, treats his soldiers and sailors, and decides to return to Batavia. In early December 1624, Ripon sails on the ship North Holland, and leaves Formosa far behind him.

This is a brief description of Ripon’s adventures in Formosa. He returns to the East Indies, and goes on to many more explorations of faraway islands, colorful descriptions of the local population and fights against the Spanish, Portuguese, and local adversaries in Sumatra, Borneo and the Moluccas.

After a couple more years of such an adventurous life, Ripon returns to his homeland, and in December 1626 sets sail back to Europe on the Dutch sailing ship Ter Tholen. According to Dutch records, the ship, together with another sailing ship, the Schiedam, arrives in the Netherlands on July 25th 1627. After that, we lose track of Ripon.

Gerrit van der Wees is a former Dutch diplomat. From 1980 through 2016 he published the Taiwan Communique. He currently teaches History of Taiwan at George Mason University.

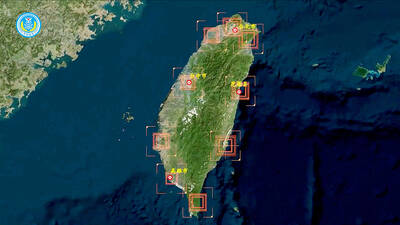

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of

Shunxian Temple (順賢宮) is luxurious. Massive, exquisitely ornamented, in pristine condition and yet varnished by the passing of time. General manager Huang Wen-jeng (黃文正) points to a ceiling in a little anteroom: a splendid painting of a tiger stares at us from above. Wherever you walk, his eyes seem riveted on you. “When you pray or when you tribute money, he is still there, looking at you,” he says. But the tiger isn’t threatening — indeed, it’s there to protect locals. Not that they may need it because Neimen District (內門) in Kaohsiung has a martial tradition dating back centuries. On