Sept. 24 to Sept. 30

Qing Dynasty admiral Shih Lang (施琅) is not only known for destroying the Tainan-based Kingdom of Tungning (東寧) in 1683, he is also remembered as the man who, despite fierce opposition, convinced China’s Kangxi Emperor to incorporate Taiwan into the empire. However, some sources show that he was secretly plotting a different fate for the island.

In the time between the decisive Battle of Penghu in July 1683 to the formal annexation of Taiwan in April 1684, Shih repeatedly brought up the issue of Taiwan. The first mention came with his victory report, stating that he wouldn’t dare decide on his own the island’s fate, and urged the emperor to either make a decision or send his officials to Fujian Province, where Shih was based.

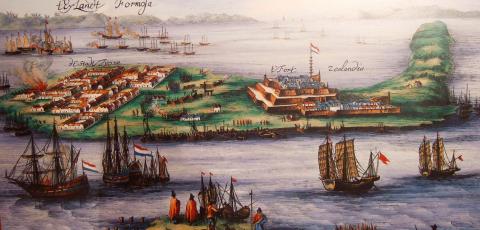

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The emperor and his top officials did not respond to Shih’s inquiries, preferring to wait until the king of Tungning, Cheng Ke-shuang (鄭克塽), formally surrendered and arrived in Beijing. While Shih argued that Taiwan had “endless stretches of fertile land... where Chinese intermixed with local savages,” most officials did not think much of Taiwan, calling it a “speck of dirt on the outer seas with naked, tattooed savages not worthy of spending our resources on,” among other disparaging remarks. Some proposed only sending troops to Penghu.

According to Chou Hsueh-yu (周雪玉) in the book, The Merits and Demerits of Shih Lang’s Invasion of Taiwan (施琅攻台的功與過), the officials who opposed Shih’s proposals because they were unfamiliar with Taiwan, worried about the cost of keeping a distant land under control and lacked understanding of maritime defenses.

Shih insisted, citing Taiwan’s strategic location and abundant natural resources, adding that foreign powers, including the Dutch who had colonized part of the island, might cause trouble for the Qing.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

THE GRAND SCHEME

A few historians speculate that there was talk about possibly handing Taiwan to the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in Batavia, which corresponds with present-day Central Jakarta in Indonesia. The Dutch were expelled by Cheng Ke-shuang’s grandfather, Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, or Koxinga), in 1662.

Chou writes in her book that it was rival official Lee Kuang-ti (李光地) who proposed allowing the Dutch to return to Taiwan in exchange for yearly tribute.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

However, Cheng Wei-chung (鄭維中) argues in his study, Admiral Shih Lang’s Secret Proposal to Return Taiwan to the VOC, that Shih was the one who plotted returning Taiwan to the Dutch.

In any event, upon the defeat of Tungning king Cheng Ke-shuang, officials in Guangdong and Fujian expected the Qing court to reverse its closure of the southeastern coast, and they started making moves to secure maritime trade rights. Some Fujianese officials had begun to entice Dutch merchants to return to the area, casually mentioning that the emperor “might even give up Taiwan,” writes Cheng Wei-chung.

On the same day that Qing officials met with the Dutch, Shih Lang delivered his report to the emperor, urging him to annex Taiwan. Meanwhile, to protect his financial interests in Fujian, he told Guangdong officials not to trade with the Europeans.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Shih’s next step was to persuade the British East India Company (EIC) and the Dutch to open offices in Fujian — a strategy that would require the emperor’s permission. Shih’s plan required some deft psychology that would convince the emperor that the British residents in Taiwan were prisoners instead of merchants, and that the EIC was grateful to the Qing for freeing them.

In turn, he would convince the emperor to demand tribute from the EIC in exchange for the right to trade in China via Fujian rather than Guangdong.

Shih also freed the Dutch prisoners who had been left behind in Taiwan after Koxinga’s conquest, including Alexander Van Gravenbroek, whom he treated with courtesy because he was fluent in Hoklo (also known as Taiwanese), the main language spoken in southeastern Fujian. Cheng Wei-chung writes that it is through Van Gravenbroek’s reports to the VOC that Shih’s plans to give Taiwan to the Dutch were revealed; there are no Chinese sources.

Shih asked Van Gravenbroek if the VOC would be interested in retaking Taiwan, and if so at what price. The Dutchman replied that the VOC wouldn’t be interested because of the dangers of the Taiwan Strait. Moreover, if they could not establish a base in China with exclusive free trade rights, governing the island would be too costly.

As with the EIC merchants before, Shih had Van Gravenbroek write a letter addressed to the emperor stating that the VOC wanted to resume trade with China, and thanking the Middle Kingdom for freeing the Dutch prisoners.

NOT SO SMOOTH SAILING

Cheng Wei-chung writes that if successful, the scheme would have greatly benefited Shih with “himself cast as the humble servant so selflessly devoted to his duty.”

Shih was banking on collecting money as the go-between for the foreign merchants and Beijing as well as taking bribes from Fujianese merchants for permission to trade with the Dutch. And finally, Fujian, where Shih had considerable economic interests, would have the upper hand against Guangdong.

However, the letters that Shih had the EIC and Van Gravenbroek write were confiscated by Fujian governor Yao Qisheng (姚啟聖), who may have been worried that the English and the Dutch would not cooperate so willingly, and might even expose Shih’s “reckless plan.” Yao also learned that the VOC had little interest in trading with Fujian.

Yao, however, died in 1684 and Shih continued his plan, attempting to convince the court to continue the maritime ban by fabricating, according to Cheng Wei-chung, a “foreign threat... so that he could be assured of being granted a monopoly on foreign trade in Xiamen and Taiwan.”

Between the noncooperation of the new Fujian governor, the emperor’s insistence on rescinding the maritime ban and Shih’s overconfidence in the VOC’s desire to trade with China and reoccupy Taiwan (they were more interested in India at that point), the plan ultimately failed.

Shih and his followers became wealthy nonetheless, claiming much of the farmland owned by the people of Tungning. He also collected tribute from Penghu fishermen, which he pocketed himself.

“This caused Taiwan’s devastation to be worse in peacetime under Shih than during the previous decades of war,” writes Shih Wan-shou (石萬壽) in the study, Discussion of Keeping or Leaving Taiwan (台灣去留之討論).

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry