Two things happened on Wednesday: The same day a seasoned television executive was brought low by a growing scandal over allegations of sexual misconduct at work, the Playboy Club reopened its doors in New York.

At the opening-night party, women in cocktail dresses and men in loafers, no socks, bumped and shimmied around an oval bar while the bunnies — comely waitresses in black corsets, rabbit ears and cottontails — offered plates of sushi and flutes of Champagne.

In a VIP area, a group of well-gelled men were manspreading, drinking and admiring passing bunnies while ignoring, in that great Playboy tradition, the fine collection of readings on the bookshelves around them: Lincoln, by Gore Vidal, The Sensuous Man, by M, Rabbit, Run, by John Updike.

Photo: AFP

While small fish nibbled at a Playboy bunny logo in a glowing saltwater tank, Playboy Chief Executive Officer Ben Kohn found a quiet hallway and explained that, actually, Playboy is in the midst of a very good year. Profits are up 25 percent, and Playboy sees lots of opportunities to expand, particularly in the US Five years ago, Playboy bailed on its licensing business in the domestic market, investing instead in places where the Playboy brand still conveyed an air of American exceptionalism. There five Playboy clubs, cafes and beer gardens in Southeast Asia and one in London.

The opening of a New York beachhead gives Playboy Enterprises a chance to reintroduce the brand in person to an American audience. In a partnership with Merchants Hospitality, the developer of various high-end New York restaurants and bars, the club will be partly open to the general public, with large sections blocked off for members. Annual dues run from US$5,000 to US$100,000, for which members can frolic freely amid the bunnies and revel in the aura of the Playboy brand — whatever it calls to mind.

CHALLENGES

The timing of all this is challenging. Hugh Hefner, the company’s founder and randy embodiment of Playboy’s revolving-bed ethos, died last year at 91. Over the years, Hefner made Playboy into a lucrative empire, in large part by marrying his libertine sexual beliefs to an upwardly mobile lifestyle: A buxom blond on each arm became a symbol of success, along with a Mercury Cougar in the driveway and a bottle of Glenfiddich on the bar.

Recently, however, insatiable bed-hopping has lost its glamour. These days, the news is strewn with stories about once-revered men who for years allegedly abused their positions of workplace power in pursuit of serial sexual conquests — in so doing, ultimately wrecking their reputations and careers. That one of the highest-stakes, horn-dogging scandals involves the president of the US allegedly covering up a covert extramarital affair with a former Playboy Playmate is a further turn of the screw for Playboy’s brand managers. An aura of pin-striped male entitlement is not what they’re after.

So, what does Brand Playboy — as embodied by its namesake magazine and sundry other media properties — stand for at a time when insatiable male sexuality has become so closely linked with comeuppance and downward mobility?

“We are taking the brand back to its libertarian and personal-freedom roots,” said Kohn. Also fun, he hastened to add. And music. And sophistication. Whether that’s enough to revive a media empire built on the appeal of nude women is another question.

#METOO

Playboy is perhaps the most extreme example of the conundrum facing masculine brands in the #MeToo era. Across the retail landscape, marketers have been tamping down the testosterone. British whiskey brand Johnnie Walker introduced “The Jane Walker Edition,” a version of the Black Label blend, complete with a female version of its iconic male logo. KFC made Reba McEntire its first female Colonel Sanders. Toyota, Nissan and Alfa Romeo announced that they would replace scantily clad women with actual product specialists at car shows. Axe Body Spray declared itself an advocate for gender sensitivity.

For a while, it looked as if Playboy, too, might turn cottontail and head for safer ground. In the fall of 2015, during the home stretch of Barack Obama’s eight-year tenure, the company announced it would no longer publish nudity in its magazine. But the relative demureness was short lived. A little more than a month after Donald Trump’s inauguration, Playboy reintroduced nudity.

Cooper Hefner, the 27-year-old son of Hugh Hefner and ’80s-era Playmate Kimberly Conrad, hopped on Twitter to explain the about-face. “I’ll be the first to admit that the way in which the magazine portrayed nudity was dated, but removing it entirely was a mistake,” wrote Hefner, now Playboy’s chief creative officer. “Nudity was never the problem because nudity isn’t a problem. Today we’re taking our identity back and reclaiming who we are.”

Shortly thereafter, his fiancee Scarlett Byrne, a British actor best known as Pansy Parkinson in the Harry Potter movies, appeared in the magazine, posing more or less nude, accompanied by a brief riff on the empowerment of equal pay and freeing the nipple. “We should not apologize for sex,” Cooper Hefner later told the Washington Post.

NEW STRATEGY

If not apologies, then what? Playboy’s strategy is, in part, to remind young Americans about the company’s history in standing up for personal liberties and free speech, said Kohn, who is also a managing partner at private equity firm Rizvi Traverse, currently the company’s largest shareholder.

“As you know, journalism is under attack every day by the White House,” he said. “But there’s also censorship on social media. Those are issues of freedom of speech, which we’ve been fighting on behalf of for 65 years, and we need to address them again going forward. Those personal freedoms, those libertarian points of view?are important to bring back.”

As for the top line, the media and entertainment properties now account for half of Playboy’s overall revenue. The other half, from licensing and partnerships, is where Kohn sees room to grow. This isn’t that surprising — the media in which Playboy has long thrived (magazines, pay-per-view porn, reality TV) have fallen on tough times, and the Internet, while a boon for pornography in general, hasn’t been kind to publishers.

The clubs, then, are Playboy’s version of what other media companies refer to as their “live events strategy.” Recode has a technology conference; The New Yorker has an annual festival; the New York Times sells travel tours with its journalists serving as expert guides. The point is making money, sure, but also to deepen the bond with brand loyalists, making them more likely to pay for subscriptions, buy merchandise, and try out products from paying sponsors.

“If you have any hope of bringing the brand back, recreating a unique live experience is the right play,” said branding expert Allen Adamson, of Brand Simple Consulting. “It’s a word-of-mouth world that we live in. People share experiences. And all things retro are currently hot. Look at all the old TV shows coming back. As younger consumers strive for authenticity, going back 50 years is a legitimate source for it. Still, it seems like a long shot.”

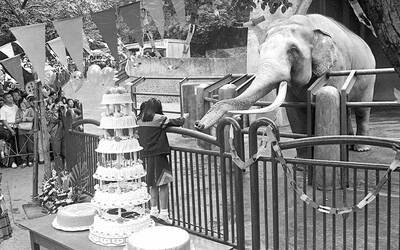

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

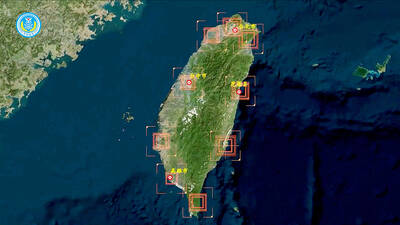

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) last week offered us a glimpse of the violence it plans against Taiwan, with two days of blockade drills conducted around the nation and live-fire exercises not far away in the East China Sea. The PRC said it had practiced hitting “simulated targets of key ports and energy facilities.” Taiwan confirmed on Thursday that PRC Coast Guard ships were directed by the its Eastern Theater Command, meaning that they are assumed to be military assets in a confrontation. Because of this, the number of assets available to the PRC navy is far, far bigger

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of