June 18 to June 24

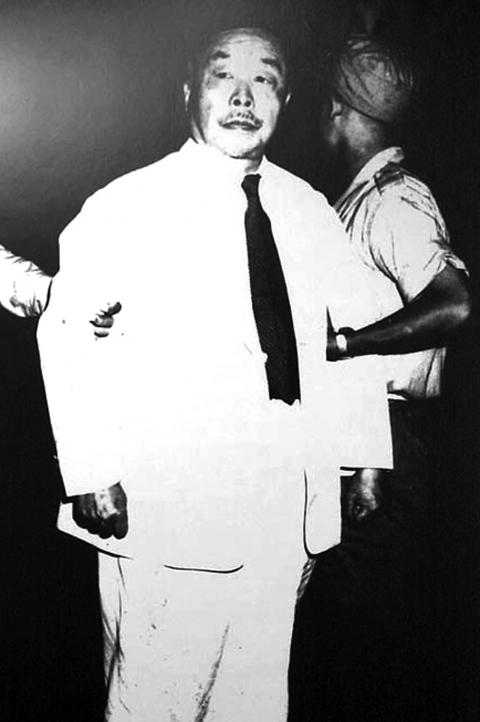

Neatly clad in a suit and tie, Chen Yi (陳儀) appears calm as the military judge in Taipei says “[t]he President has personally ordered your execution. Do you have anything to say?”

The signal is given, and Chen walks forward before two bullets strike him in his back. He collapses, but is still breathing. The executioner walks over and delivers the fatal shot. On June 18, 1950, Chen died in the place where his name would forever be tied to in history. He remains the highest-ranking military officer executed by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT).

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

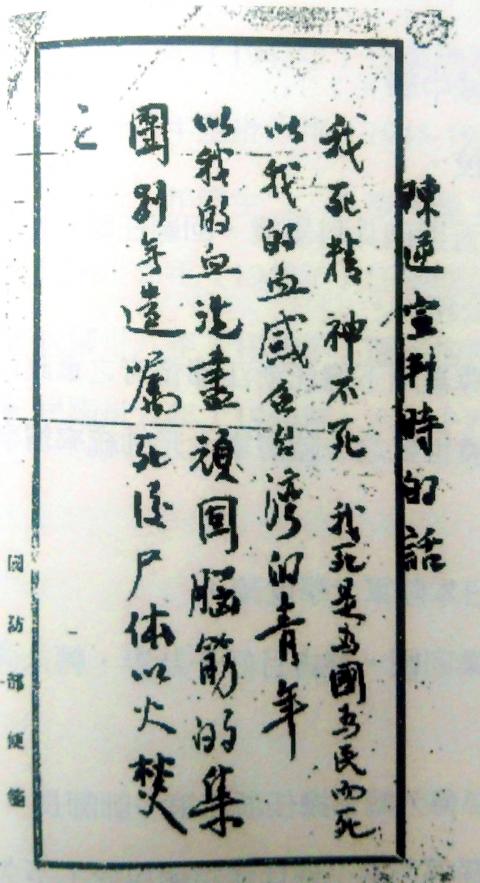

“My body may die but my spirit will live on,” Chen is recorded to have said after his sentencing. “My death will be for our citizens; my blood will inspire the young people of Taiwan; my blood will wash away these stubborn cliques. I don’t have any will; just cremate me after I’m dead.”

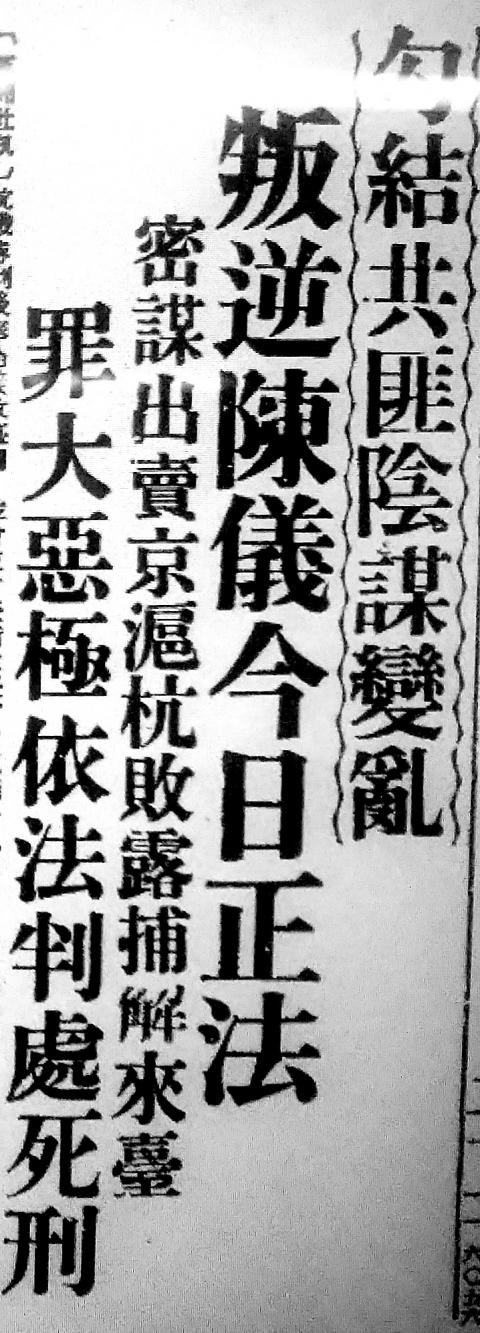

‘ONCE-A-GENERATION VILLAIN’

Chen’s execution ran as the top story on the front page of the state-run Central Daily News (中央日報) for two straight days. The story, “Colluding with communist bandits and plotting rebellion, the traitorous Chen Yi is executed today,” was printed on June 18, and on June 19 the paper (and several others) ran a follow-up story complete with graphic photos of the execution. Even his cremation was mocked, with the paper writing, “this once-a-generation villain should be reduced to ashes within the next eight hours.”

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

The initial report was less than kind, as it even bashes Chen’s early days: “Chen began his career with the [Chinese] warlords, but he was an opportunistic man and left them to join the KMT revolutionaries. Our government decided to overlook his past and treated him well, hoping that he could turn a new leaf and devote himself to our cause. He enjoyed his status as high-ranking official for most of his life, but who would have thought that his brain was still full of bureaucratic warlord ideals?”

“His rule of Taiwan was reckless and ill-advised, and at the moment of crisis for our country, he was only looking out for himself. He has no understanding of our revolutionary spirit, and had absolutely no confidence in our battle against the communist bandits,” the Central Daily News wrote.

Chen is an often vilified figure as he was presiding over Taiwan when the 228 Incident, an anti-government uprising that was violently suppressed, broke out on Feb. 28, 1947, although his exact role in the incident is still debated. However, he was also known for his unwavering patriotism toward the Republic of China, idealistic political views and loyalty to the KMT. So what did he do to earn the wrath of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石)?

Photo courtesy of National Central Library

After the 228 Incident, international pressure, especially from the US, called for Chiang to dismiss Chen, who resigned from his post on March 18, 1947. Chiang not only lamented Chen’s departure, but assigned him another post as provincial governor of his native Zhejiang Province, where the Chinese Civil War was still raging on. However, Chiang’s diary shows otherwise — he was furious about Chen’s mishandling of the event.

The Central Daily News article accuses Chen of betraying the KMT forces in Beijing, Shanghai and Hangzhou and surrendering to the advancing People’s Liberation Army troops in the winter of 1948, allowing them to cross the Yangtze River the following year. It listed three major pieces of evidence to Chen’s betrayal, including letters he wrote to his subordinates that included various terms of surrender.

The second-page editorial in the same edition, “The fate of the treasonous,” goes into more detail, stating that Chen tried to persuade general Tang Enbo (湯恩伯) to regionally surrender to the communists, but Tang instead apprehended Chen and escorted him to Taiwan for a year-long investigation.

“Chen has committed the most heinous crime and more than deserves to die,” the editorial states. “We believe that the decision by the highest military court is justified.”

PEACE SEEKER?

“Everything I did was for the troops and civilians of Beijing, Shanghai and Hangzhou,” Chen is reported to have said right before his execution. What did he mean?

There are two books that attempt to tell Chen’s story from a more balanced, or even favorable perspective, examining his entire life and career and what led to his downfall: The True Face of Chen Yi (陳儀本來的面目) by Chen Chao-hsi (陳兆熙) and An Elegy for Chen Yi:Giving His All for His Ideas (陳儀: 為理想一生懸命的悲歌) by Wang Chih-hsiang (王之湘).

Wang writes that upon his return to China, Chen realized that the outcome of the war was pretty much determined and that engaging further would only harm the people of his homeland.

“Chen believed that he needed to restore order to the masses, which indicates that he opposed the war and sought peace. For Chiang, however, that would mean handing the entire country to the enemy. There was no room for peace in his eyes,” Wang writes.

When Chiang temporarily stepped down temporarily during peace talks with the communists in January 1949, Chen wrote a letter to Tang informing him his plans to maintain “regional peace,” including releasing prisoners of war and halting the army’s advance, but Tang turned these in to Chiang’s agents, and Chen was relieved from his post and placed under house arrest.

Chen was detained for over a year, eventually being transferred to Taiwan in April 1949. His old friends urged him to apologize to Chiang but Chen refused, denying any wrongdoing. Even Tang begged Chiang to spare Chen’s life.

Chen Chao-hsi confirms Wang’s claims, that as a career military man Chen knew about the devastation of war and wanted to spare his people from further suffering. In a letter written to his daughter, Chen Yi states that he was too old to have any personal ambition and he approached the communists solely so that she — and other young people — in China would have a chance for a better life.

Chen Chao-hsi adds that Chiang did not want to execute Chen Yi, but that with everything going wrong for the KMT, Chiang needed to kill someone of Chen’s stature to make a statement. He adds that Chiang may also have executed Chen to pacify the Taiwanese, who still deeply mistrusted the KMT due to the 228 Incident. Thus, the execution would be killing two birds with one stone.

“Also, Chen Yi never admitted his wrongdoings to Chiang, so Chiang finally had him killed,” Chen Chao-hsi concludes.

An untitled poem by Chen Yi aptly sums up his fate: “My life and career has been full of tragedy, how will I be seen in the cycle of history?”

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern