Taiwan was once a province of China, but for only a brief period: 1887 to 1895, and the era laid the foundation for a separate identity in Taiwan.

Two hundred years earlier, in 1644, the Qing Dynasty under Manchu rule had come to power in Beijing, driving out the Ming Dynasty rulers. But at the time, Taiwan was under Dutch colonial rule through the Dutch United East India Company.

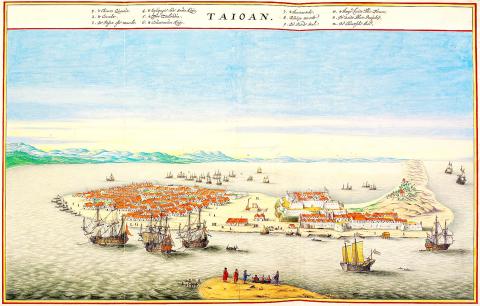

In April 1661, Ming warlord Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功, also known as Koxinga) — himself being on the run from the Qing invaders — crossed over to Taiwan with some 400 ships and 25,000 men, and after a nine-month siege of Zeelandia, a Dutch fortress in present-day Tainan, took control of the area.

Photo courtesy of Wikemedia Commons

The rule of Koxinga’s family didn’t last long: in 1683 his grandson, Cheng Ke-shuang (鄭克塽), was defeated in a battle on the outlying island of Penghu (the Pescadores) by the famed admiral Shih Lang (施琅), the first official to rule Taiwan on behalf of the Qing. Then for 200 years, Taiwan was ruled from Fujian Province in a turbulent period known to have an “uprising every three years and a rebellion every five,” as one Qing official stated at the time.

GLOBAL TRADE

During these 200 years, Taiwan became a quiet backwater, with very little interaction with the global economy. This changed in the 1850s, when the advent of the steamship made it possible for Western nations to travel far and wide. In the mid 1850s, US Admiral Perry and his “Black Ships” were in the area and even proposed to Washington to make Taiwan an American trading hub, in part to counter the influence of the other Western nations expanding into the region: France, England and Germany.

Photo courtesy of Wikemedia Commons

In the early 1870s Japan made military incursions into the area in order to punish local pirates, while from 1884 to 1885 France briefly occupied northern Taiwan. The Japanese expansion and the French episode convinced the Qing court in Beijing that it was necessary to pay more attention to Taiwan, and governor Liu Ming-chuan (劉銘傳) was asked by the Court to prepare to make Taiwan a province in its own right.

Liu’s first order of business was to try to bring the Aboriginal population under his control: from 1885 through 1887 he conducted three major military campaigns but lost one-third of his men, while in the end only one-third of Aboriginal areas were under his control. Still, in 1887 Taiwan was officially declared a province of China, and Liu was made its first governor.

MODERNIZATION

Photo courtesy of Wikemedia Commons

Once in office, Liu started an extensive process of modernization. He felt constrained by the old capital Tainan — too many small winding streets —and proposed to move the capital to Taichung, where he laid out a grid for a modern city and started to build many new buildings, city walls, gates and imperial offices. However, cost overruns put a halt to the project.

Still, in the next few years Taiwan went through a period of frantic modernization: a modern telegraph line connected north and south, electric streetlights started to line the streets, a taxicab service with rickshaws was initiated and a modern railroad was built between Keelung, Taipei and Hsinchu. With the help of European trading houses, Taiwan became a major trading hub again, exporting tea, camphor, sugar and rice.

The renewed interaction with the West put Taiwan on the map again for Europe and also for the young American republic. Small European communities sprouted in Tainan and Taipei: traders and missionaries, who set up schools, clinics and hospitals. Missionary Thomas Barclay in Tainan set up the first ever printing press, and started publishing Presbyterian Taiwan Church News.

Much of this new vitality and innovation was possible as Taiwanese were frontiersmen and pioneers, much more open to innovation than tradition-bound Chinese officialdom in Beijing.

DISTINCT IDENTITY

Liu also tolerated dissent and his policies started to attract intellectuals from China, escaping the oppressive atmosphere under the late Qing dynasty rule. The mix of these intellectuals and local gentry brought about a flourishing culture of art and literature. It resulted in the birth of a local identity that saw itself as distinct from China. This also formed the powerbase for the subsequent Formosa Republic.

But Liu’s policies and expansion created resentment and jealousy at the Qing Court. In 1891 he was recalled to China, and retired to Anhui Province. He was succeeded by Shao Yu-lien (邵友濂), who was governor until 1894. Shao’s major achievement was the definitive move of the capital from Tainan. However, the eventual destination was Taipei, which had become the center of political activity.

INCOMPETENCE

Shao’s rule was mostly known for its rampant corruption and ineffective government. He stopped or reversed many of the new modernization projects and innovations started by his predecessor. He was ordered to prepare Taiwan for defense against Japan, but purchased old and useless weapons, pocketing the difference. To his credit, he did bring in the famous “Black Flag” Liu, who would later play a major role in the Formosa Republic.

The ineffectual Shao was replaced by governor Tang Ching-sung (唐景崧), who had fought against the French in the South. Tang had fought together with “Black Flag” general Liu Yung-fu, who received the command of some 100,000 soldiers.

TREATY OF SHIMONOSEKI

However, war had broken out between China and Japan over control over Korea. China lost and under the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, it ceded Taiwan to Japan.

The treaty was signed on behalf of the Qing government by viceroy Li Hongzhang (李鴻章). Under its provisions, China recognized the independence of Korea, ceded Taiwan and Penghu in perpetuity to Japan, paid a huge war indemnity and opened port-cities to trade.

Back in Taiwan, the treaty came as a total surprise. Neither the population nor officials had been consulted. On May 23, 1895, Governor Tang was convinced by local gentry to declare an independent Formosa Republic, the first independent republic in Asia. A new government was inaugurated on May 25, 1895.

While during this brief interlude of eight years, Taiwan was indeed ruled as a province of China, at the same time the era established a more solid basis for a separate Taiwanese identity: a multicultural mix of the Aboriginal, Hakka and Hokkien heritages.

The earlier settlers were frontiersmen who had mainly engaged in agriculture and local trade. Along with the gentry, they had always had an independent streak, fighting off foreign control on numerous occasions. The intelligentsia and literati who arrived during the late 1880s did so to escape the stifling climate in Beijing under the Manchu rulers. The combination proved to be a powerful mix, which laid the basis for both the Formosa Republic and the early resistance against the Japanese.

Gerrit van der Wees is a former Dutch diplomat. From 1980 through 2016 he served as the editor of Taiwan Communique.

The 1990s were a turbulent time for the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) patronage factions. For a look at how they formed, check out the March 2 “Deep Dives.” In the boom years of the 1980s and 1990s the factions amassed fortunes from corruption, access to the levers of local government and prime access to property. They also moved into industries like construction and the gravel business, devastating river ecosystems while the governments they controlled looked the other way. By this period, the factions had largely carved out geographical feifdoms in the local jurisdictions the national KMT restrained them to. For example,

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

With over 100 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of