Indian cuisine has struggled to find its place in Taiwan’s international food scene. Not rare enough to be cast among the “exotic” types that have but a handful of representative restaurants in Taipei (think Peruvian, Russian or even Turkish), nor popular enough to join the mainstream giants (Italian, Thai, Korean), it occupies a culinary no man’s land where most restaurants stick to the predictable Taj Mahal formula to get noticed.

My passion for the condiments of the subcontinent began back in college, cooking with my Indian roommate. Years spent bonding over the rituals of onion chopping and roti tossing, we not only forged a lasting friendship, but also fine-honed a string of curries that have been the talk of countless dinner parties I’ve hosted since. I’m the kind of person who has a list of favorite Indian restaurants, and I’m always looking to add to it.

And so it was with high hopes that my wife and I came to Saathiya (莎堤亞), located on a second floor on Xinyi Road (信義路), just above Dongmen MRT Station (東門). You’d miss it if it weren’t for the orange, green and white menu stand at the bottom of the stairwell. Nothing, (except perhaps the Taj Mahal), says Indian restaurant quite like the country’s trademark tricolor.

.jpg)

Photo: Liam Gibson

We sit by a large window at the far end of the space which overlooks Xinyi Road. Its low-key for a Saturday night. The place is almost empty except for a couple of tables. The walls of the place are lined with abstract paintings of a remarkably consistent style, courtesy of the owner’s friend and long-term Taiwan resident, artist Sagar Telekar. The paintings are aesthetically pleasing, but stand in jarring contrast next to the flat-screen monitor playing an MTV-like stream of Bollywood dance scenes. The seats are Ikea-chic: simple, black and covered with a nice padding that upon second squeeze feels like one of those thick, cushy mouse pads that gamers use.

We are served by a young Mongolian waiter/waitress duo. Neither can speak Chinese, (nor Hindi for that matter), “Only English,” they say. My wife lets me order.

Flavoring a curry’s gravy with methi (fenugreek seed powder) takes experience. Believed to have special medicinal properties, it’s something of an acquired taste, even in India. I’ve ruined plenty of curries crossing the threshold where stimulating acidic bite becomes bittery awfulness. Saathiya’s methi malai paneer (NT$350) past the test. The methi flavor is subtle, but noticeable, just as it should be.

Photo: Liam Gibson

A plain lassi (NT$100) is a must if you’re sampling multiple curries in one sitting. Its tangy/salty sharpness helps bring your palate back to ground zero in a quick neutralizing gulp. This one delivered the palate-purging hit and a satisfying mouthful of yoghurt-milky frothy goodness.

The aloo paratha (NT$125) was a major disappointment. Undercooked, damp, oily and served on ugly pieces of paper towel.

One critical test for any restaurant, but especially so for Indian ones, is whether or not they can tailor the spice level to your specifications. Saathiya needs to work on this. I asked for the Hyderabadi special chicken curry (NT$380) to be very spicy and it was medium, at best. If they can’t get it right using their preferred English, I can’t imagine how they’d fare in Mandarin.

Photo: Liam Gibson

The spinach-based gravy of the palak paneer (NT$320) was smooth, thick and just a little pulpy. Unfortunately, that was all this dish got right. The paneer was sliced into cubic pieces, chewy but bland. Lightly frying paneer with jeera (cumin seeds) really transforms its flavor. But it seems they’d rather skimp on the seeds here, and so its aromatic potential was left unrealized. Inch-sized onion slices were an unpleasant surprise. This faux pas would have been permissible if it were accompanied by other veggies such as bell peppers, (as is usual in dishes like paneer tikka masala), but as it was the only vegetable in the gravy, it was hard to overlook.

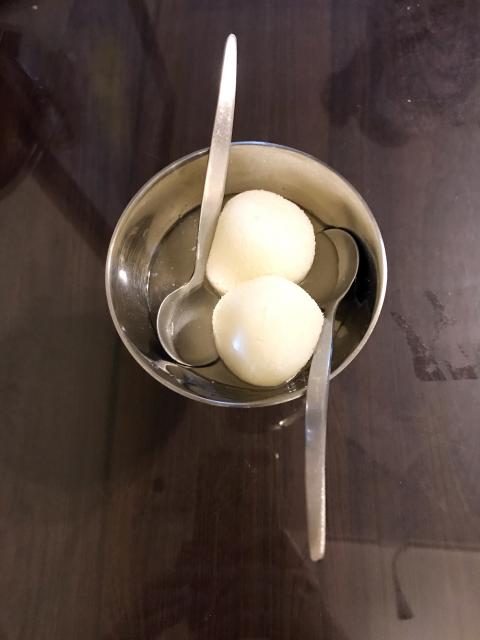

For desert, we ordered rasgulla (NT$90) as gulab jamun wasn’t available. Two white balls come soaked in a little pool of syrup. To really relish the heady-sensation it offers, rasgulla, like gulab jamun, should be taken in one bite. One bite of heavenly bliss. The ball’s sponginess resists the weight of your jaws as they slowly clamp down, letting the syrup slowly ooze and flow out over your teeth and tongue. The sponge becomes firmer as you push into the core before finally splitting and filling your cavity with a sugary mouthful of sinful proportions.

I wish the rest of the meal had delivered similar levels of sensory satisfaction, but all in all, it was hit and miss. At just over a year old, Saathiya is a new arrival on Taipei’s indistinct Indian scene, and like a toddler, still trying to find its feet. Above the MRT, it’s very accessible and a stroll around the pretty backstreets of Dongmen is nice after dinner. Yet I wouldn’t go out of my way to come back to Saathiya.

Photo: Liam Gibson

Photo: Liam Gibson

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

US President Donald Trump’s bid to take back control of the Panama Canal has put his counterpart Jose Raul Mulino in a difficult position and revived fears in the Central American country that US military bases will return. After Trump vowed to reclaim the interoceanic waterway from Chinese influence, US Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth signed an agreement with the Mulino administration last week for the US to deploy troops in areas adjacent to the canal. For more than two decades, after handing over control of the strategically vital waterway to Panama in 1999 and dismantling the bases that protected it, Washington has