July 3 to July 9

Japan had just celebrated the 20th anniversary of its rule over Taiwan when Yu Ching-fang (余清芳), self-appointed Grand Marshal of the Benevolent Nation of the Great Ming (大明慈悲國), declared war against the colonial government.

On July 6, 1915, Yu announced that he had been “appointed by heaven to rally the righteous and drive out the bandits.” He lamented that Japan, which was once tributary to imperial China, had “betrayed its master” and invaded its territory.

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I have gathered the heroes of the four seas to attack and annihilate the ‘dwarf bandits.’ Providing peace to the good while rooting out the violent, I shall ease the people’s suffering and save the lives of all living beings,” Yu said.

Thus began the Tapani Incident (?吧哖事件), the largest and last armed anti-Japanese revolt by Han Chinese. The toll on the Taiwanese side is still disputed, with some sources claiming up to 30,000 deaths. The latest numbers released by the Tainan City Cultural Affairs Bureau in 2015 indicate 1,412 dead and 1,421 sentenced, which excludes two districts in Kaohsiung where the records have been lost.

VARYING MOTIVES

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Academia Sinica researcher Paul Katz writes in When the Valleys Turn Blood Red that not all participants shared Yu’s nationalist and patriotic sentiments toward China, which had transitioned from the Qing Empire to the Republic of China. Some wanted to establish an imperial state in Taiwan with Yu or another rebel leader as emperor, and others spoke of an independent Taiwan.

Katz adds that many did not share Yu’s distaste of being ruled by foreigners, but were more unhappy about the way they were ruled. The Japanese reviewed the causes of the rebellion in a newspaper article, citing excessive taxes, Japanese arrogance and police brutality, among other factors. During interrogation sessions, many rebels cited these factors, but Katz argues that “the ethnicity of their overlords did not appear to have been a decisive factor.”

He gives the example of a laborer, who stated during his interrogation that “all I wanted was to farm in peace, not have to pay taxes and open up new forest lands at will.”

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“We now have to pay huge amount of taxes, and all profitable enterprises have been monopolized by the Japanese … I couldn’t take it anymore. If we could become part of China again, we would no longer have to suffer like this,” complained another rebel.

Some also say they joined because Yu had promised them prominent positions, land and tax breaks if the uprising succeeded.

“We should at least consider the possibility that many participants … chose to act as the result of more mundane sentiments such as a desire for material gain or simply to be left alone,” Katz writes.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The most interesting cause, however, was Yu’s use of folk religion and messianic rhetoric that included an impending apocalypse and salvation. This was nothing new, as Katz writes that these beliefs had been circulating around southern Taiwan for some time.

“Some recruits may have joined Yu’s cause … merely as a means of protecting themselves and their families from an impending apocalypse,” Katz writes.

RELIGIOUS PERSUASION

The first indication of Yu’s anti-Japanese tendencies surfaced in 1909, when the 30-year-old former patrolman was sent to a vagrant camp for joining a secret society that aspired to overthrow the colonial government. Katz writes that Yu’s uprising shared several similarities to this group, including the “belief in an imminent apocalypse, the promised arrival of a rescue force of soldiers from China and the advent of a savior who lived in the mountains and possessed a magic sword and imperial seal.”

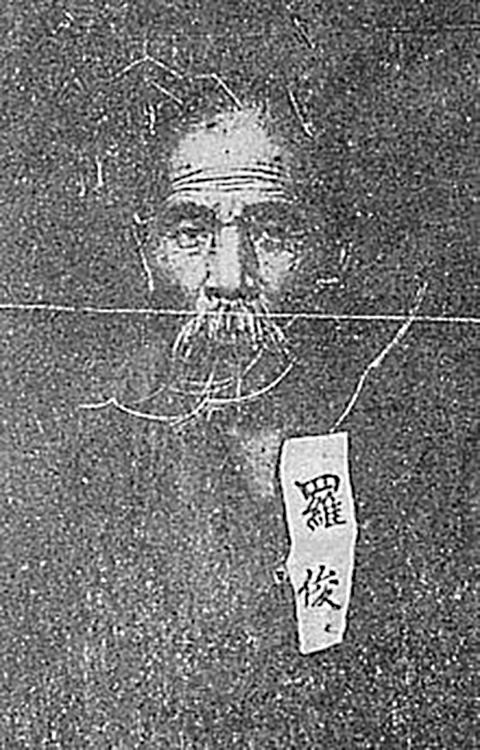

Upon his release, Yu became associated with the Hsilai Temple (西來庵) and started recruiting followers across Taiwan in 1914, also raising money for the uprising under the guise of temple repairs. He met and joined forces with co-conspirators Lo Chun (羅俊) and Chiang Ting (江定) during this time.

Yu proclaimed that the temple’s deity told him that Japanese rule would only last 20 years, and the end was near. The three leaders propagated the idea of a savior born near Tainan who could heal sicknesses and was destined to become Taiwan’s emperor, with some followers even believing that person was Yu, according to Chiu Cheng-lue’s (邱政略) book, Looking Back 100 Years After the Tapani Incident (百年回首?吧哖事件).

“Regardless of gender and age, all followers had to kneel down before Yu,” Chiu adds.

The leaders also had their followers purchase amulets that, combined with following a vegetarian diet for 49 days and reciting prayers, would make them impregnable to swords and bullets, adding that they could disable the Japanese soldiers through magic and annihilate them within three days.

The leaders claimed that the time would be ready to strike when the sky turned dark for seven days and the reinforcements from China arrived.

Unfortunately, the Japanese caught wind of the plan and started arresting the rebels, including Lo. Yu briefly went into hiding before making his edict and started attacking various police stations in the area. The Japanese retaliated, culminating in the major clash in Tapani, located in today’s Yujing District (玉井) in Tainan.

Yu’s forces didn’t stand a chance despite his magical claims. He was betrayed by locals during a feast and arrested just a month after the rebellion. He was executed in September. Chiang held out until the next spring, but was also caught and hung, effectively ending the resistance.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On Jan. 17, Beijing announced that it would allow residents of Shanghai and Fujian Province to visit Taiwan. The two sides are still working out the details. President William Lai (賴清德) has been promoting cross-strait tourism, perhaps to soften the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) attitudes, perhaps as a sop to international and local opinion leaders. Likely the latter, since many observers understand that the twin drivers of cross-strait tourism — the belief that Chinese tourists will bring money into Taiwan, and the belief that tourism will create better relations — are both false. CHINESE TOURISM PIPE DREAM Back in July

Could Taiwan’s democracy be at risk? There is a lot of apocalyptic commentary right now suggesting that this is the case, but it is always a conspiracy by the other guys — our side is firmly on the side of protecting democracy and always has been, unlike them! The situation is nowhere near that bleak — yet. The concern is that the power struggle between the opposition Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and their now effectively pan-blue allies the Taiwan People’s Party (TPP) and the ruling Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) intensifies to the point where democratic functions start to break down. Both

Taiwan doesn’t have a lot of railways, but its network has plenty of history. The government-owned entity that last year became the Taiwan Railway Corp (TRC) has been operating trains since 1891. During the 1895-1945 period of Japanese rule, the colonial government made huge investments in rail infrastructure. The northern port city of Keelung was connected to Kaohsiung in the south. New lines appeared in Pingtung, Yilan and the Hualien-Taitung region. Railway enthusiasts exploring Taiwan will find plenty to amuse themselves. Taipei will soon gain its second rail-themed museum. Elsewhere there’s a number of endearing branch lines and rolling-stock collections, some

This was not supposed to be an election year. The local media is billing it as the “2025 great recall era” (2025大罷免時代) or the “2025 great recall wave” (2025大罷免潮), with many now just shortening it to “great recall.” As of this writing the number of campaigns that have submitted the requisite one percent of eligible voters signatures in legislative districts is 51 — 35 targeting Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) caucus lawmakers and 16 targeting Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) lawmakers. The pan-green side has more as they started earlier. Many recall campaigns are billing themselves as “Winter Bluebirds” after the “Bluebird Action”