Jan. 15 to Jan. 22

Japanese prime minister Ito Hirobumi declared war on opium in Taiwan on April 10, 1895, declaring that the colonial government would be able to “quickly eradicate” the widespread vice in their soon-to-be-acquired territory.

That day was the fourth negotiation between the Qing and Japanese empires, as Li Hongzhang (李鴻章) made a final attempt to dissuade Japan from taking over Taiwan by emphasizing the long-standing habit among its inhabitants.

Photo: Chen Chin-min, Taipei Times

“There have been people living in Taiwan long before the arrival of opium,” Ito replied. “We will strictly prohibit the import of the drug, and nobody in Taiwan will be able to smoke.”

When Li warned Ito that such measures might lead to unrest, Ito replied, “That will be the Japanese Empire’s responsibility.”

Han Chinese settlers in Taiwan had been smoking opium for centuries by then — a Qing Dynasty report from 1724 condemned the practice, stating that it was a vice that needed to be curbed immediately.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

But the habit only became more widespread, especially after the Opium Wars in China, which led to the forced legalization of the drug in 1860. Liu Ming-hsiu (劉明修) writes in the book Ruling Taiwan and its Opium Problem (統治台灣與鴉片問題) that between 1864 and 1881, the amount of legal opium imported into Taiwan each year increased from 59,820kg to 352,843kg. And by 1892, the opium trade accounted for more than half of Taiwan’s total revenue.

During the Japanese invasion of Taiwan, resistance leaders even fabricated a Japanese-issued opium prohibition edict to rally addicts to join their ranks, Liu writes. In response, the government temporarily allowed Taiwanese to continue smoking while making it punishable by death to supply the drug to Japanese troops, and later all Japanese nationals.

After the resistance fell in late 1895, the great debate began between proponents of immediate and gradual prohibition. The immediate prohibition camp was mainly concerned that the opium habit would spread to Japan if not curbed right away.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The gradual camp countered by stating that Japanese were not likely to become addicts because of their proclivity to alcohol, which did not mix well with opium. This claim was widely accepted. They also proposed a government monopoly over the manufacturing and sale of opium. Although the government claimed that it chose this path out of benevolence, Liu writes that the real reasons were to avoid further conflict with Taiwanese and also to boost government revenue.

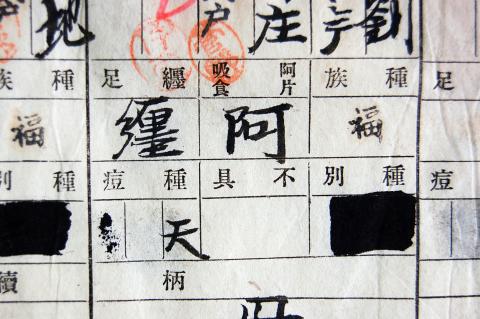

On Jan. 21, 1897, the Japanese colonial government issued the Taiwan Opium Edict, which established the government monopoly and restricted purchase to “proven addicts” with special licenses, with no new licenses issued. In addition, all vendors and users would have to pay a usage fee to the government. Violators were either sent to jail or fined.

There was no verifiable method to show that one was an addict, and Liu writes that essentially anyone over 20 years old who applied would likely have their license approved.

The process took three years because of continued armed resistance, epidemics and people unwilling to pay the usage fee. When the government declared the process complete and cut off registration, there were 169,064 license holders.

However, Liu writes that while legal opium users decreased over the years, the number of illegal users only increased. In 1908, the government launched a mass raid, arresting more than 17,000 illegal users. However, 15,863 of them were deemed “incurable addicts” and given licenses instead.

It was a lucrative venture for the government, as opium revenue accounted for as high as 46.3 percent of the colony’s total in 1898, according to statistics found in Liu’s book. As the number of legal users dropped, the government tried to export the opium and turn it into morphine. They also increased the prices yearly.

During the 1920s, Taiwan’s intellectual elite accused the government of delaying the eradication process so they could keep making money. After repeated protests, they took the issue to the League of Nations, upon which the government started implementing treatment programs and facilities for addicts.

However, the colonial government never relinquished their monopoly, only ceasing to produce the drug in 1944 when opium poppies were needed to make anesthesia during World War II. And they never stopped selling until June 1945 — just two months before surrender.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry