The first thing that needs to be stated about this excellent book is how well it’s written. There’s not a shred of academic jargon here. Absent, too, are tiresome references to other people’s research in parentheses to support every statement. Should you notice these things at the start, you’d be right in seeing in them a foretaste, even a guarantee, of the straightforwardness and honesty of what is to come. Accidental State, in other words, is a pleasure to read, and of how many academic books these days can that be said?

You might think that Lin Hsiao-ting’s (林孝庭) credentials, which include Oxford, Stanford, National Taiwan University and Harvard (his publisher here), would guarantee these qualities. Unfortunately no university these days is immune to the infection of dreary academic convention, so that Lin deserves credit for these shining virtues entirely in his own right.

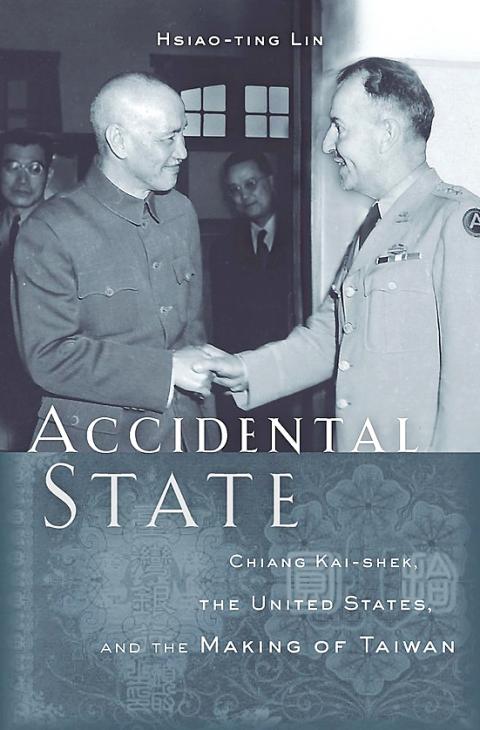

The book looks at the first few years of Taiwan’s history under the rule of Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石). What it argues is that the popular view that the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) migrated here en masse in late 1949, and then ruled the country with US support, overlooks many complicating subtleties, some revealed in documents — KMT archives, ROC official files, personal papers of some top Taiwanese leaders, British documents — only recently made public.

First, Chiang didn’t immediately see Taiwan as the only territory he could fall back on — there were enclaves in China where the KMT was still in control, notably Hainan Island, an area of Myanmar bordering on Yunnan and many off-shore islands, and these all held out possibilities. Secondly, the US wasn’t immediately convinced of Chiang’s viability for support, and some of its diplomatic initiatives were the work of individuals on the ground working quasi-independently. Thirdly, Chiang was encountering serious difficulties with other senior KMT personnel, some of whom refused to obey his orders. He wasn’t, in other words, the undisputed KMT leader in Taipei until after the US government finally decided he was the best channel through which to donate arms and funds.

Of the individuals acting semi-independently in Taiwan, by far the most important looked at in this book is Charles Cooke, a retired US admiral. Not only was he responsible for having surplus US gasoline and ammunition from Japan sold to Chiang at preferential prices but, much more importantly, his advice was crucial in persuading the Nationalists to abandon both Hainan Island and the Zhoushan Islands in the spring of 1950.

This was all only months after US president Harry Truman had announced at a press conference on Jan. 5, 1950 that there would be no US involvement in the Chinese Civil War — something that had, in the eyes of a many observers, effectively already finished — and that there would be no US assistance or advice given to the Nationalists on Taiwan.

THE REDS ARE COMING

What dramatically changed Washington’s attitudes was Beijing’s pact with Moscow of February 1950, four months before the outbreak of the Korean War on June 25. This treaty, together with a successful Soviet atomic bomb test in August 1949, made it suddenly seem as if communism was an international movement capable of expanding both into Europe and into East Asia. Should Soviet forces ever begin to operate out of Taiwan, for instance, their extension eastwards to Japan and southward to the Philippines, and then the rest of the Pacific, would be hard to counteract. And so it was that, on June 27, 1950, only three days after the outbreak of war in Korea, Truman announced that he had ordered the Seventh Fleet into the waters between Taiwan and China.

Even so, tensions between Chiang and the US continued. Washington rejected Chiang’s offer of 33,000 of his best troops to fight alongside UN forces in Korea (on the grounds of the legitimacy any acceptance would give to the status of Taiwan), and Chiang disagreed with the US preference for a Nationalist attempt to retake Hainan Island after it was lost to the Communists (though he later appeared to change his mind), opting instead for raids on the Fujian and Zhejiang coasts with the unadvertised support of the CIA.

The Nationalist enclave in northern Myanmar under Li Mi (李彌), which had made some disastrous forays into Yunnan Province, and some 23,000 Nationalists interned by the French in Indochina, were both finally brought back to Taipei, leaving the coastal raids all that remained of the grand project of re-taking China. A secret Japanese organization aiming to train the Nationalists on Taiwan, largely ignored by scholars according to the author, is also discussed.

Chiang, this book implies, never really envisaged a full-scale assault on the Chinese mainland, but used plans for such a contingency as part of his negotiation strategy with Washington. Finally, on Dec. 2, 1954, a mutual defense treaty between the US and the Republic of China (ROC) was signed. Its provision that US approval was necessary before any invasion of the mainland was attempted, however, was not revealed, so as not to shatter the hopes of the Taiwanese population.

What this book argues, then, is that the various forces involved stumbled towards the eventual situation whereby Taiwan effectively became what Lin calls a “client state” of the US. Initially, Chiang was considering other possibilities, the US remained unconvinced and the KMT itself was divided. Everyone acknowledges that what changed everything was the Korean War, which persuaded the US that Taiwan was crucial to the East Asian balance of power.

What Lin does in this fine book is examine the confused situation that existed from 1949 to 1954, leading up to the KMT’s realization that the game was up in China and the decision by the Americans to finally sign a formal treaty with Taipei. The security of Taiwan, the “accidental state” of the book’s title, and Chiang’s predominance therein, were both from that moment assured.

On April 26, The Lancet published a letter from two doctors at Taichung-based China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) warning that “Taiwan’s Health Care System is on the Brink of Collapse.” The authors said that “Years of policy inaction and mismanagement of resources have led to the National Health Insurance system operating under unsustainable conditions.” The pushback was immediate. Errors in the paper were quickly identified and publicized, to discredit the authors (the hospital apologized). CNA reported that CMUH said the letter described Taiwan in 2021 as having 62 nurses per 10,000 people, when the correct number was 78 nurses per 10,000

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

May 5 to May 11 What started out as friction between Taiwanese students at Taichung First High School and a Japanese head cook escalated dramatically over the first two weeks of May 1927. It began on April 30 when the cook’s wife knew that lotus starch used in that night’s dinner had rat feces in it, but failed to inform staff until the meal was already prepared. The students believed that her silence was intentional, and filed a complaint. The school’s Japanese administrators sided with the cook’s family, dismissing the students as troublemakers and clamping down on their freedoms — with

As Donald Trump’s executive order in March led to the shuttering of Voice of America (VOA) — the global broadcaster whose roots date back to the fight against Nazi propaganda — he quickly attracted support from figures not used to aligning themselves with any US administration. Trump had ordered the US Agency for Global Media, the federal agency that funds VOA and other groups promoting independent journalism overseas, to be “eliminated to the maximum extent consistent with applicable law.” The decision suddenly halted programming in 49 languages to more than 425 million people. In Moscow, Margarita Simonyan, the hardline editor-in-chief of the