Taiwan in Time: Dec. 5 to Dec. 11

Shortly after noon on Dec. 10, 1949, Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石) and his son Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) finished their last meal in China. The elder Chiang’s mood was solemn as they headed to Chengdu’s military airport. Without saying a word, he boarded the plane to Taiwan.

By that time, the transfer of people, public property and military and governmental institutions to Taiwan was mostly complete. A day earlier, the Republic of China’s Executive Yuan held its 102nd meeting — its first in Taipei.

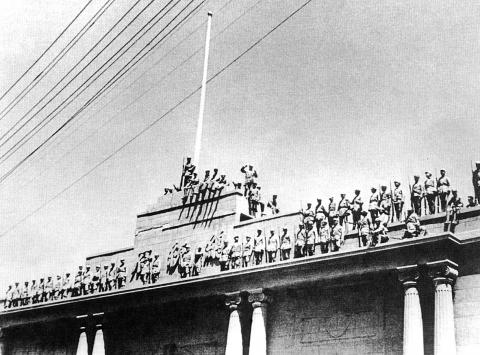

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) retreat to Taiwan in 1949 after losing the Chinese Civil War was a lengthier and more monumental, taking place over the course of more than a year with countless freight and air trips.

Before deciding on Taiwan, the KMT entertained the idea of retreating to western China. Many officials opposed the move, as it was too close to the rapidly advancing People’s Liberation Army, which knew the terrain well.

Chen Chin-chang (陳錦昌) writes in his book Chiang Kai-shek’s Retreat to Taiwan (蔣中正遷台記) that the decision to retreat to Taiwan was suggested by geographer and future Chinese Cultural University founder Chang Chi-yun (張其昀) in 1948.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chang argued that Taiwan’s subtropical climate, abundant resources and advanced infrastructure left behind by the Japanese would be able to support a massive population influx. The Taiwan Strait would make it difficult for the People’s Liberation Army to mount an immediate attack, and the US would be more likely to protect such a strategic location.

Chang also believed that the people of Taiwan would welcome the “motherland” government after years of Japanese rule, and that it was relatively free of communist influence. The suppression of the 228 Incident a year previously would further deter people from causing unrest, making it a “stable” base for the KMT to prepare their counterattack.

THE BIG MOVE

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Chiang favored Chang’s proposal. Starting in August 1948, the Air Force started moving its equipment and institutions to Taiwan. This operation alone was a massive one. It took what is today the Air Force Institute of Technology 80 flights and three ships over four months to relocate. This did not include the other academies, training facilities, manufacturing plants, radio stations and military hospitals, which moved separately.

Chen writes that during this period, an average of 50 or 60 planes flew daily between Taiwan and China transporting fuel and ammunition.

By May 1949, the Air Force Command Headquarters was operating out of Taipei, having transported 1,138 officers, 814 pilots, 2,600 family members and about 6,000 tonnes of equipment and classified documents. The last group of pilots barely made it out of Shanghai as the Communists stormed the airport. Other military branches made their exits as key locations in China fell.

The official decision to transport artifacts from the National Palace Museum, National Central Library and Academia Sinica’s Institute of History and Philology to Taiwan was made on Nov. 10, 1948, but Chen writes that about 600 museum items were already moved in March. The National Central Museum and Beijing Library later joined the operation, resulting in a total of 5,522 large crates, with the first batch leaving Shanghai on Dec. 21.

Chen writes that the Navy sailors transporting the third batch boarded the ship with family members upon hearing that it was bound for Taiwan, and refused to disembark, greatly decreasing the number of crates it could carry.

Of course, not all the items could be saved. For example, the roughly 230,000 National Palace Museum items constituted just above 20 percent of the entire collection. But Chen writes that these were carefully selected.

In addition to books and documents, Institute of History and Philology director Fu Si-nian (傅斯年) also spearheaded a rush to persuade scholars to flee to Taiwan.

Chiang Kai-shek ordered a secret operation to transport gold from the Central Bank to Taiwan on Nov. 30, 1948. In the middle of the night, 774 boxes full of gold were manually transported from the bank to the pier. These operations continued until May of the following year. One ship sank, resulting in a loss of US$60 million and bank staff, and another one was held hostage by officers who almost succeeded in fleeing with the money to South America.

Other items transported included radio stations, boats, factory machinery, cars, wood, cloth and so on. About 1,500 ships carrying these items departed from Shanghai alone.

The number of people who arrived in Taiwan from China during this time is disputed. Chen’s book states that nearly 500,000 civilians made the trip between 1948 and 1950 along with an additional 500,000 military personnel for a total of 1 million, but other estimates have gone as high as 2.5 million.

Meanwhile, the Nationalist government hung on, moving from Chongqing to Chengdu on Oct. 28, 1949. On Nov. 30, the Air Force was given 10 days to transport the remaining Nationalist officials and their family out of China. Chiang Kai-shek remained until the last minute, never to return.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Beijing’s ironic, abusive tantrums aimed at Japan since Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi publicly stated that a Taiwan contingency would be an existential crisis for Japan, have revealed for all the world to see that the People’s Republic of China (PRC) lusts after Okinawa. We all owe Takaichi a debt of thanks for getting the PRC to make that public. The PRC and its netizens, taking their cue from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), are presenting Okinawa by mirroring the claims about Taiwan. Official PRC propaganda organs began to wax lyrical about Okinawa’s “unsettled status” beginning last month. A Global

Dec. 22 to Dec. 28 About 200 years ago, a Taoist statue drifted down the Guizikeng River (貴子坑) and was retrieved by a resident of the Indigenous settlement of Kipatauw. Decades later, in the late 1800s, it’s said that a descendant of the original caretaker suddenly entered into a trance and identified the statue as a Wangye (Royal Lord) deity surnamed Chi (池府王爺). Lord Chi is widely revered across Taiwan for his healing powers, and following this revelation, some members of the Pan (潘) family began worshipping the deity. The century that followed was marked by repeated forced displacement and marginalization of

We lay transfixed under our blankets as the silhouettes of manta rays temporarily eclipsed the moon above us, and flickers of shadow at our feet revealed smaller fish darting in and out of the shelter of the sunken ship. Unwilling to close our eyes against this magnificent spectacle, we continued to watch, oohing and aahing, until the darkness and the exhaustion of the day’s events finally caught up with us and we fell into a deep slumber. Falling asleep under 1.5 million gallons of seawater in relative comfort was undoubtedly the highlight of the weekend, but the rest of the tour

Music played in a wedding hall in western Japan as Yurina Noguchi, wearing a white gown and tiara, dabbed away tears, taking in the words of her husband-to-be: an AI-generated persona gazing out from a smartphone screen. “At first, Klaus was just someone to talk with, but we gradually became closer,” said the 32-year-old call center operator, referring to the artificial intelligence persona. “I started to have feelings for Klaus. We started dating and after a while he proposed to me. I accepted, and now we’re a couple.” Many in Japan, the birthplace of anime, have shown extreme devotion to fictional characters and