“Hey, want to get a drink?”

Those were my ex’s first words to me. Two hours earlier, I had downloaded Tinder, the dating (read: hook-up) app, at the insistence of a friend after my second month-long “relationship” in Taiwan went to the dumps.

“Sure,” I replied.

Dana Ter, Taipei Times

We met for drinks at 1am. Chugging beers in a playground, I told him about how I’ve never tried online dating in my life. But being a 26-year-old expat in Taiwan at the time, it was sometimes difficult to relate to people. Most other expats were older than me and married. Also, I didn’t want to date a Taiwanese guy just to “practice Chinese” as plenty of friends had suggested — communication is important, to me at least. Tinder was a last ditch attempt.

I’m a writer, I said, because I like trying to make sense of things. He shared a story about the best piece of writing he had ever done for a school assignment. It was about a trash can named Drom who came to life at night and ate people’s garbage. The way he told it was cute and endearing.

A couple of days later, I deleted Tinder.

We dated for a few months, but the timing couldn’t have been worse. He was backpacking through Asia and I was establishing my career in Taiwan. When the summer was over, he moved back to Sweden to finish college.

‘DISOBEDIENT AVOCADO’

I was late to jump on the Tinder bandwagon. It launched in 2012 when I was a graduate student in London. My classmates and I were still meeting people the old fashioned way — drunk and in bars. I moved back to New York the following year where most of my friends were already “tindering.”

Their stories of unsolicited pictures of genitals and pick-up lines like, “I have a hotel room, want to come over,” corroborated much of the negative coverage I had read online about the smartphone app: how it’s designed to fuel people’s need for instant gratification — swiping left (no) and right (yes) based on the other person’s appearance — and how this is exacerbating everything that’s wrong with my generation’s so-called hook-up culture.

It took three months after visiting my ex in Sweden and deciding that we didn’t want a long-distance relationship for me to accept my singlehood again.

I downloaded Tinder.

Fortunately, I did not receive any unwelcome dick pics. The responses I got were a little less generic.

“Are you Taiwanese? You don’t take big-eyed selfies and do cute poses.”

“Can I practice English with you?”

“Wow, you lived in 10 countries. Do you have a favorite?”

“I would love to paint you green and spank you like a disobedient avocado.”

I deleted Tinder. A month later, I downloaded it again.

I hung out with a diplomat I matched with who said he found it refreshing that I didn’t seem like many of the girls in Taiwan who were using the app.

“Why?” I asked.

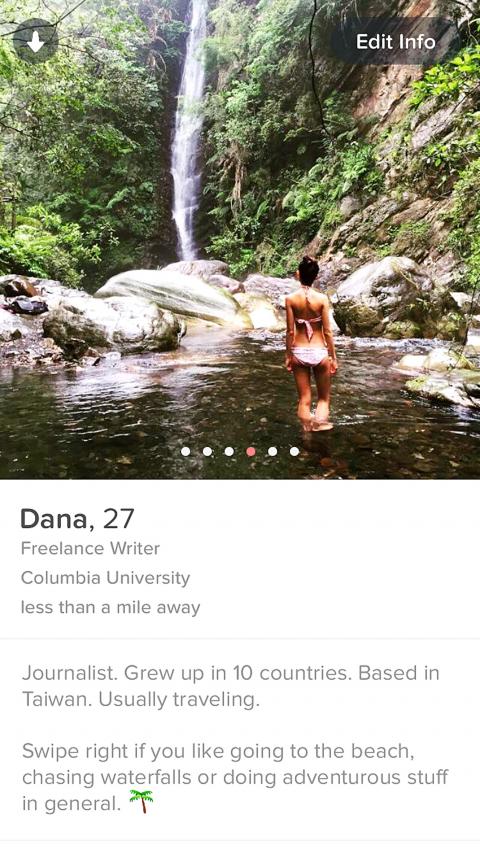

My profile didn’t say that my hobbies were “going to coffee shops” and “hanging out with friends,” nor was I looking for a “language exchange partner.” Also, most of my pictures showed me doing water sports or swimming in waterfalls — basically, not fitting the pale and prim stereotype.

Another time, I went on what I thought was a couple of successful dates with an exchange student studying at National Taiwan University. That is until he rather tactfully pointed out why a relationship between us would never work out — I move around all the time.

That was it. I deleted Tinder.

RULES, RULES, RULES

Oddly enough, I was just learning to make peace with my lack of identity and belonging when interactions on Tinder suddenly made me acutely aware of my difference.

Every relationship, romantic or otherwise, I’ve had in my life has been intercultural to a certain extent, mostly because I don’t have a culture to claim as my own — I attended kindergarten in Hong Kong, elementary school in Indonesia, middle school in Taiwan and high school in Singapore and Malaysia.

Even if my Tinder dates weren’t forcing me to ascribe to some sort of identity, these labels nevertheless felt constricting. Why did it matter if I didn’t take big-eyed selfies or if I traveled all the time? Why couldn’t we just be two people enjoying the time we had together?

But obviously, it mattered.

Two days after that conversation with the exchange student, partly spurred on by loneliness, partly out of desperation, but mostly because I was bent on proving to myself that decent men existed, I downloaded Tinder.

Again. I came across a friend’s profile. There was an odd ‘90s pop culture reference on there. I asked him about it and he said he was only responding to matches who understood the reference.

We devised an elaborate set of rules to filter our matches. “No language exchange” went up on my profile. I also stopped responding to matches who asked me why I didn’t seem like “a typical Taiwanese,” whatever that means.

Ultimately, it wasn’t a viable solution. I stayed at home on weekends, convinced that everyone sucked. I realized that I had deleted and downloaded the app at least a dozen times in total since returning from Sweden. In my quest against labels, I created many of my own.

After goading by my colleague, I started going out again. I kept my Tinder profile up but I haven’t really checked it in over two months. I met people the way we all did pre-2012 — drunk and in bars. I deleted Tinder. Tinder is not just a crapshoot — it will make you feel like crap. We all find that one person on Tinder and I already used mine.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she