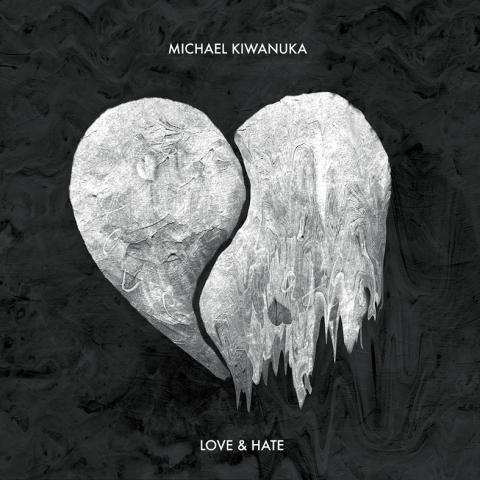

Love & Hate, Michael Kiwanuka, Interscope Records

In times of pain and fear, the past can feel like a refuge. Michael Kiwanuka’s second album, Love & Hate, is a sustained, stylized plunge into despair: plaints of isolation, doubt, lovelessness, racial injustice, longing, hopelessness and a certain resolve despite it all, often set to mournful minor chords. “Love and hate — how much more are we supposed to tolerate?” he asks in the title song, before quietly insisting, “You can’t break me down.”

The album’s comforts lie in its spacious retro sound. The producer Danger Mouse places Kiwanuka in a realm of string orchestras and wordless backup chorales, of rich reverb and staticky vintage-amp distortion, of unprogrammed drums and leisurely buildups. Kiwanuka’s voice doesn’t appear until halfway through the 10-minute opening song, Cold Little Heart — after an overture of quivering strings and a female chorus singing oohs and ahs, patiently transporting the song and the album to an early-1960s soundstage.

Kiwanuka, a 29-year-old Englishman whose parents are from Uganda, isn’t the only songwriter who’s decisively turning his back on the synthesized constructs of mainstream R&B. Maxwell’s new album, BlackSUMMERS’night, revels in the textures of hand-played physical instruments; so does The Dreaming Room, by Laura Mvula. Like Kiwanuka, they connect organic sounds to a sense of idealism, pointedly harking back to songwriters like Marvin Gaye and Curtis Mayfield, who channeled pleasure toward larger aspirations.

Kiwanuka’s 2012 debut album, Home Again, offered more naturalistic folk-soul. It featured him and his guitar in small-band arrangements that evoked Bill Withers, Terry Callier and Van Morrison. That side of Kiwanuka’s music reappears in One More Night, a Stax-style soul song about clinging to hope, and in the album’s first single, Black Man in a White World, a complex declaration of identity, with a field-holler-like melody set to handclaps, tricky funk syncopations from Kiwanuka’s own guitar and bass tracks and jabs of disco strings. “I’m not fighting/But I’ve got something on my mind/Making me sad, making me mad,” he sings.

But most of the album invokes the kind of cinematic artifice, at once old-fashioned and openly reconstituted, that Danger Mouse has also brought to his own projects, like Broken Bells. Danger Mouse, aka Brian Burton, is partial to stubbornly slow tempos and a melancholy undertow, using strings and voices as ghostly reinforcements and letting notes echo into the shadowy distance.

Throughout the album, Kiwanuka sings as if he were in some private purgatory, offering incantations only he will hear. He doesn’t raise his voice; graininess thickens his tone at vulnerable moments, then ebbs away, and his phrases are far more likely to taper off than to push toward a peak. The music makes space for him to ache.

Falling, written by Kiwanuka and Burton, has the singer reluctantly pushing back against the chance to restart a troubled romance: “You’re telling me you want me now/Let me go, leave my head alone.” He’s all by himself, yet surrounded by phantoms: Tremulous organ chords waft up; a guitar hesitantly follows the descent of the vocal line; a tambourine makes sparse shivers; and women’s voices float in the distance, like Lorelei’s. It’s doleful, but it’s also plush — a Danger Mouse specialty that suits Kiwanuka nicely.

Songs like Place I Belong and I’ll Never Love are resigned to utter solitude; “Rule the World” is a plea for someone to “Show me love, show me happiness/I can’t do this on my own,” but it’s a plea that goes unfulfilled. In Father’s Child, he sings, “I’ve been searching for miles and miles/Looking for someone to walk with me,” and an optimistic buildup toward the middle — with some rare major chords — hints that he’ll find someone; instead, the song turns slow and pleading, leaving the search unfinished.

The Final Frame ends the album with reflections on a long relationship unraveling. It’s an apology and a confession of numbness and distance, cast as a bluesy dirge with discreetly hovering strings and extended solos from Kiwanuka’s cutting lead guitar. All the singer can promise is that the couple will “float away in our parade of love and pain.” The only consolations are in the way the song revives and fulfills a classic R&B ballad form, the way the guitar flails and cries, and the sense that for all the elegant artifice, something desperate and honest is being sung.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she