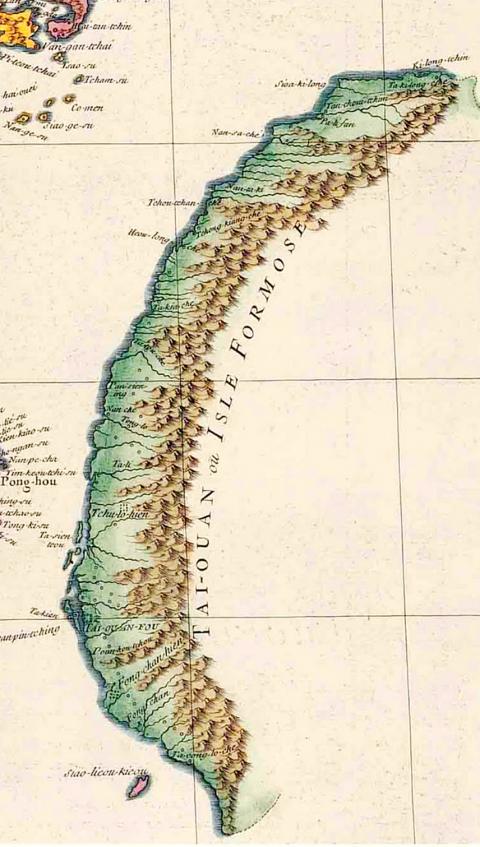

Taiwan in Time: May 9 to May. 15

In 1874, former Xiamen consul Charles Le Gendre published a pamphlet titled, Is Aboriginal Formosa a Part of the Qing Empire? An Unbiased Statement of the Question.

The topic of interest was timely as it encapsulated much of the international debate before and after the Japanese military expedition to the Hengchun Peninsula (恆春半島 ) in response to the killing of 54 shipwrecked Ryukyuan sailors by Paiwan Aborigines.

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Le Gendre had negotiated with Aborigines several years prior when they killed several shipwrecked Americans. He later traveled to Japan and became a political consultant who encouraged Japan to colonize the Aboriginal areas of Taiwan, as he considered them to belong to no country.

The military expedition and the resulting conflict, known as the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件), ended with the Qing paying the Japanese to retreat. After the incident, the imperial court, which had long seen Taiwan as a backwater province unworthy of development, started to pay more attention to what was then still part of Fujian Province.

BEYOND REACH

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Historian Wu Mi-cha (吳密察) writes in the preface to The Expedition to Formosa (征臺記事) that the Qing considered Taiwan, in its own words, “beyond the reach of our whip.”

The imperial court restricted cross-strait immigration and forbade settlers from moving into the eastern and southern regions populated by Aborigines as a form of population control, partially in fear of Taiwan becoming a sanctuary for renegades — not unlike the time when anti-Qing leader Cheng Cheng-kung (鄭成功), better known as Koxinga, used it as his base in 1661. Few troops were stationed to prevent a mutiny, Wu writes.

The Qing had always expected unrest to come from within — so it was a surprise when they heard that Japan had attacked, even though the troops landed on the Hengchun Peninsula, one of the Aboriginal areas.

Historian Lin Cheng-jung (林呈蓉) writes in her book, The Truth Behind the Mudan Incident (牡丹社事件的真相) that one required a separate passport — which curiously had to be obtained through the British consulate in Kaohsiung or Tainan — to enter such areas. The passport clearly stated that the region was outside of government jurisdiction.

Although Japanese troops landed on Taiwan on May 2, 1874, the Qing did not formally respond until May 11, when it released a statement requesting the Japanese to withdraw its troops, claiming that Japan had violated the Sino-Japanese Friendship and Trade Treaty, signed only three years previously.

On May 23, a ship carrying a Qing official arrived, demanding that the Japanese withdraw. Lin writes that the official did not even disembark, delivering the message and heading back to China — a telling sign the the empire was in decline, as it could not even send an army to deal with the fewer than 3,000 Japanese soldiers suffering from various tropical diseases.

OUT OF THE BACKWATERS

It was not until the Japanese and the Aborigines had already fought their battles and were in peace talks that Shen Baozhen (沈葆楨), China’s minister of naval affairs, arrived on June 21.

Lin writes that Shen not only did not protest Japan’s behavior, but stated his regret in “not being able to aid in the punishment of the Aborigine perpetrators.” In the prefectural capital of Tainan, Qing officials posted public notices stating that the government had obtained word from Japan that no more locals would be harmed, creating the false impression that they were in charge.

Imperial policy on Taiwan changed due to this event, realizing that passive governance would only lead to similar incidents and further questioning of its authority. China finally started developing the territory it had claimed since 1683.

Shen spent about a year in Taiwan after the incident as imperial commissioner. He commissioned Western-style fortifications in Tainan, including the Eternal Golden Castle fortress (億載金城), hired Western experts to help train soldiers, experiment with mechanical coal mining and install electricity, and he sent naval students to study in Europe.

First of all, per Shen’s suggestion, the government lifted the immigration restrictions and the ban on entering Aboriginal areas, and in fact even encouraged it. To “open up” and pacify (often by force) the Aboriginal mountain areas, three major roads were built in the north, central and south. Shen also changed the administrative structure of Taiwan.

To prevent more shipwrecks, the Qing — partly under international pressure — commissioned the construction of the Oluanpi Lighthouse (鵝鑾鼻燈塔) at the southernmost point of Taiwan a year later. Shen also divided Taiwan into smaller administrative regions, and Taipei Prefecture was born during this time.

Despite the Qing’s efforts, Taiwan was invaded again a decade later when the Sino-French war spilled across the strait.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

On a harsh winter afternoon last month, 2,000 protesters marched and chanted slogans such as “CCP out” and “Korea for Koreans” in Seoul’s popular Gangnam District. Participants — mostly students — wore caps printed with the Chinese characters for “exterminate communism” (滅共) and held banners reading “Heaven will destroy the Chinese Communist Party” (天滅中共). During the march, Park Jun-young, the leader of the protest organizer “Free University,” a conservative youth movement, who was on a hunger strike, collapsed after delivering a speech in sub-zero temperatures and was later hospitalized. Several protesters shaved their heads at the end of the demonstration. A

In August of 1949 American journalist Darrell Berrigan toured occupied Formosa and on Aug. 13 published “Should We Grab Formosa?” in the Saturday Evening Post. Berrigan, cataloguing the numerous horrors of corruption and looting the occupying Republic of China (ROC) was inflicting on the locals, advocated outright annexation of Taiwan by the US. He contended the islanders would welcome that. Berrigan also observed that the islanders were planning another revolt, and wrote of their “island nationalism.” The US position on Taiwan was well known there, and islanders, he said, had told him of US official statements that Taiwan had not

The term “pirates” as used in Asia was a European term that, as scholar of Asian pirate history Robert J. Antony has observed, became globalized during the European colonial era. Indeed, European colonial administrators often contemptuously dismissed entire Asian peoples or polities as “pirates,” a term that in practice meant raiders not sanctioned by any European state. For example, an image of the American punitive action against the indigenous people in 1867 was styled in Harper’s Weekly as “Attack of United States Marines and Sailors on the pirates of the island of Formosa, East Indies.” The status of such raiders in

On a sweltering summer night 30 years ago, infant Li Yuanpeng was finally fast asleep, nestled between his parents, when a group of men burst into their home in southern China’s Guangdong province. They beat Chen Mingxia and her husband and tied them up as baby Li, in his pale green gown and whorl of dark hair, wailed from the bed. It was the last time they would ever see their son. They “took my child away,” Chen said between sobs. Baby Li was kidnapped in 1995 when China’s one-child policy was in force and child-trafficking was rampant. While no official data