Taiwan in Time: April 4 to April 10

Deng Nan-jung’s (鄭南榕) magazine had 18 licenses, 22 publication names and was shut down by the government 44 times over five years — but it always hit the shelves on time. But this time, they got him.

On April 7, 1989, armed police broke their way into the office of Freedom Era Weekly (自由時代) on Minquan E Road (民權東路) in Taipei. Amid the confusion, Deng, who had barricaded himself in the building for the previous 71 days, slipped into his private office, where he had stored three cans of gasoline and a lighter.

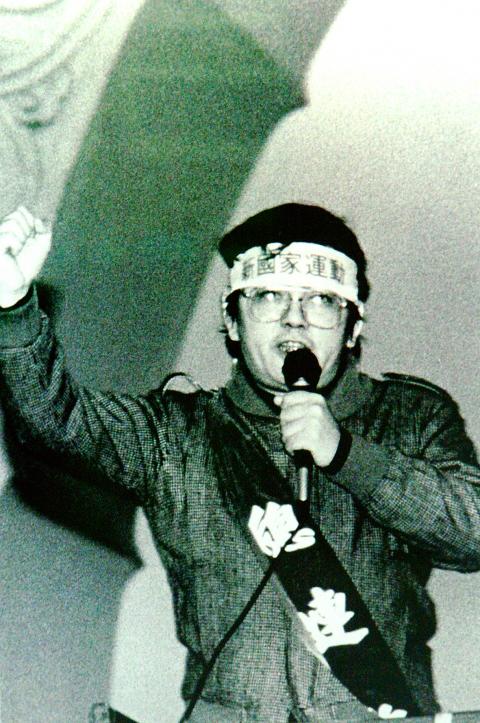

Photo courtesy of Deng Liberty Foundation

By the time someone noticed, Deng had already locked the door from inside and set the room on fire. He did not survive.

He earned many monikers in the media aftermath: “madman,” “martyr,” “lone ranger,” and “the weirdo from the philosophy department,” courtesy of United Evening News (聯合晚報).

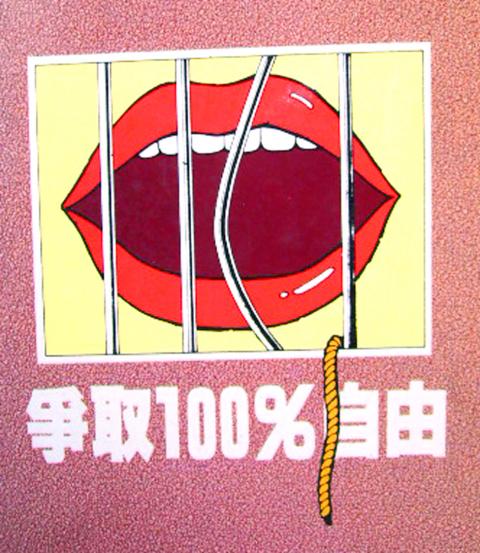

The mission of Deng’s magazine was to “fight for 100 percent freedom of speech.” Today, the street where it happened is officially named Freedom Lane (自由巷) and in December last year, Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) designated April 7 Freedom of Speech Day.

Photo courtesy of Deng Liberty Foundation

Deng was well-known by the government as an outspoken democracy activist who claimed he had no fear of arrest or death. From the day he publicly declared his support for Taiwanese independence during a speech at Jinhua Junior High in Taipei, he would keep testing the government’s limits.

He finally committed the ultimate political taboo by publishing a draft of the constitution for a Republic of Taiwan in its entirety on Dec. 10, 1988, Human Rights Day. Penned by Japan-based independence activist Koh Se-kai (許世楷), the first article called for a free, independent Taiwan, “made up of people who have decided to recognize Taiwan as their motherland for eternity.”

Even though martial law had been lifted the previous year, it was still a crime to advocate “splitting the country’s territory.” The ruling Republic of China government’s claim on both Taiwan and China was not to be questioned, and publishing the draft was the ultimate call for freedom of speech, which Deng considered the “most basic right in a democracy” and something that needs to be fought for even when “facing the barrel of a gun.”

Photo courtesy of Deng Liberty Foundation

Deng did not found the magazine until 1984 at age 37, but his rebellious side could be seen early, as he is said to not have graduated from college because he refused to take a course on Sun Yat-sen (孫逸仙) thought.

The magazine often ran negative articles about president Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國), criticized martial law as well as repeatedly brought up taboo subjects under martial law such as the 228 Incident. It serialized Henry Liu’s (劉宜良) unauthorized biography on Chiang after the writer was murdered, allegedly under government orders. The “100 percent freedom of speech” mission was printed on every cover.

Ho Chien-ming (何建銘) writes in the study Freedom Era Weekly and Taiwanese Democracy Movements in the Late 1980s (自由時代系列雜誌與1980後期台灣民主運動) that Deng was one of the few activist magazine publishers who also organized events. Deng was one of the masterminds behind the Green Movement protests on May 19, 1986, calling for the lifting of martial law on the 36th anniversary of its declaration, as well as the first 228 Incident march on the event’s 40th anniversary.

In 1987, Deng made his famous (or infamous) declaration, which historian Hu Hui-ling (胡慧玲) writes in the Taiwan Historical Society’s (台灣歷史學會) Window on Taiwan (台灣之窗) column that it was the first time someone dared to publicly do so in Taiwan.

In November that year, Deng reportedly slapped legislator Chu Kao-cheng (朱高正) in the face after Chu tried to stop him from distributing independence pamphlets at the Democratic Progressive Party’s second national meeting.

After he received the court summons for sedition in January 1989, Deng announced that he would not be captured alive and barricaded himself in the magazine’s office. The site is now the Deng Nan-jung Memorial Museum, and a section of the office remains as it was after the blaze.

Deng was not the only person who self-immolated, during this time. Just a month later during his funeral, activist Chan I-hua (詹益華) also set himself on fire in front of the Presidential Office.

The magazine survived Deng’s death, with his brother at the helm until it closed due to financial troubles in November 1989.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry