Chen Chia-hong (陳佳虹) always avoided a deserted building close to the beach in Taoyuan’s Guanyin District (觀音).

“It just wasn’t something you would go near,” she says.

Earlier this year, however, Chen not only tried to enter the locked building, but learned that it was part of a NT$15 million renovation in 2010 by the government-owned coastal recreational area, which had sat idle for nine years after it was abandoned.

Photo courtesy of Hsu Hsin-yun

After the renovation, the site enjoyed a few years of popularity, but then fell into disuse after the beach was listed by the fire department as one of the city’s 10 most dangerous places to swim.

This is not a unique case — nor is it the nation’s most expensive idle public property. There is the NT$600 million fitness center at Tainan’s Southern Taiwan Science Park (南部科學工業園區), the NT$3.1 billion Linnei Waste Incineration Plant (林內焚化爐) in Yunlin and the whopping NT$123 billion Changhua Coastal Industrial Park (彰化濱海工業區), which isn’t abandoned but has a high vacancy rate — up to 64 percent in one of the park’s three subdivisions.

Since 2010, artist Yao Jui-chung (姚瑞中) and his students at National Taiwan Normal University, including Chen, have been documenting these sites, dubbed “mosquito halls” (蚊子館) since insects are often the only occupants. Their effort has yielded four books covering more than 400 sites.

Photo courtesy of Hsu Hsin-yun

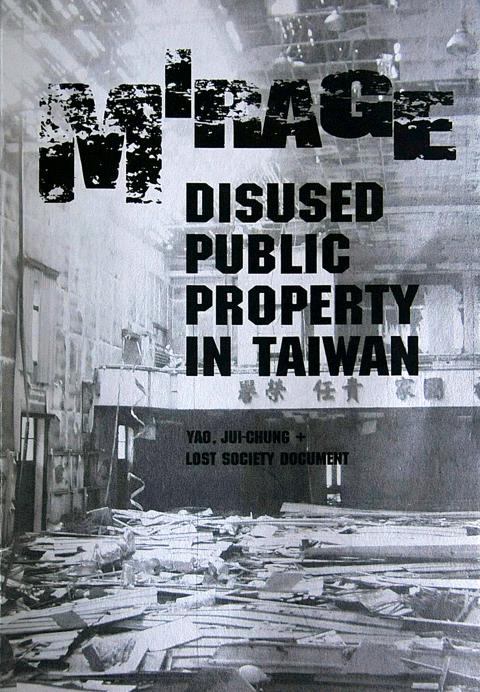

Yao released the first English edition of Mirage: Disused Public Property in Taiwan earlier this month in preparation for the project’s inclusion in the 20th Biennale of Sydney under the group name Yao Jui-chung + Lost Society Document. The biennale begins Friday.

“I also hope this can serve as a case study, as [mosquito halls] are a global phenomenon,” Yao says. “I want people to be aware that this problem can be addressed.”

After the released of each volume, Yao sends a copy to relevant government institutions around nation. He plans to release his fifth Chinese edition on May 21, a day after president-elect Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文) takes office.

Photo courtesy of Hsu Hsin-yun

“It’s an experiment to test the efficiency of the new government,” he says.

MOSQUITO HALLS

The English-language edition features 100 representative properties selected from the four Chinese books, although Yao says he did not include projects that have successfully been revitalized. It is divided into 10 chapters, including industrial parks, markets and recreational facilities. Along with stark black-and-white photographs, each entry lists the address, who commissioned it, who manages it and cost as well as a brief summary.

Yao says many sites exist because local governments wanted fast and tangible political achievements as a way to win votes. He cites the Ministry of Transportation and Communication’s “car park for every town” project and the more recent “park site” spree, where localities are rushing to create cultural creative parks, industrial parks and so on.

“Eagerness for a visible result, overly optimistic estimation in usage, inadequate planning and bad design, inadequate subsequent funds for construction, repair and operation” are some of the reasons, Yao says, that these places fell into disuse. Corruption and collusion also play a part, and many cases are simply swept under the rug and ignored.

“When the regular administrative channels are paralyzed, civil society must apply pressure on them,” Yao says.

Others are victims of social change — empty barracks due to decreased military activity and abandoned schools due to Taiwan’s plummeting birth rate.

Yao says the books have forced the central government to address the issue. Shortly after the publication of the first book, he received a call from the Presidential Office and met with then-premier Wu Den-yih (吳敦義) to discuss the issue. The government now has a watch list of mosquito halls, with about 80 percent of the list coming from Yao and his students’ research.

Problems, however, persist, including getting local governments to voluntarily report their sites and institutions passing the buck and bogging down the process.

REVIVING THE DEAD

Yao says local governments may have their budgets slashed if they do not show that they are addressing sites in their jurisdiction, and he now serves on the committee for site revitalization.

While some governments have responded by hastily demolishing their mosquito halls, Yao says the best way is to reuse it for something else — preferably for small businesses, community organizations, nonprofits, art institutions or disadvantaged groups. More often than not, however, they end up under the management of large corporations.

The abandoned dorms of Beitou’s Fangyi Elementary School (方義國小) are an example of how new life can be breathed into these old buildings. The school is now used as a practice space for performance groups in coordination with the Taipei City Department of Cultural Affairs.

Officials may use several methods to circumvent full revitalization, such as closed revitalization, where the government simply starts using it as storage space, and false revitalization, where they change the signage, put up some posters, throw in some new furniture and consider the project complete.

OUT OF THE CAVE

Chen, who studied painting, had no idea what she was getting into when she signed up for Yao’s class. Now every time she walks past an abandoned building, she wonders if there are any plans for it.

“Using art to examine society is a significant component of performance art,” Yao says.

About 230 students have worked with him throughout the years, each assigned to identify, investigate and photograph mosquito halls in their hometowns.

Some students, especially foreign ones, were sent to islands such as Matsu and Kinmen.

“I hope it can awaken their social awareness,” Yao says. “I hope they walk out of the classroom and look at this absurd situation and find out why. Art not only can reflect the visible reality but also reveal the true nature underneath.”

Yao says his students are surprised that many sites they documented in the first volume were demolished, as they never thought that their schoolwork could make a difference.

“This project allowed me to step into society, leave my cave,” Chinese painting major Lee Ching-yu (李謦羽) says.

“If you just stay in your room and do what you’re told to do, life is quite empty. Now there’s a goal, an ideal you can achieve. You can change society or reveal something for the public to see,” Lee adds.

Towering high above Taiwan’s capital city at 508 meters, Taipei 101 dominates the skyline. The earthquake-proof skyscraper of steel and glass has captured the imagination of professional rock climber Alex Honnold for more than a decade. Tomorrow morning, he will climb it in his signature free solo style — without ropes or protective equipment. And Netflix will broadcast it — live. The event’s announcement has drawn both excitement and trepidation, as well as some concerns over the ethical implications of attempting such a high-risk endeavor on live broadcast. Many have questioned Honnold’s desire to continues his free-solo climbs now that he’s a

As Taiwan’s second most populous city, Taichung looms large in the electoral map. Taiwanese political commentators describe it — along with neighboring Changhua County — as Taiwan’s “swing states” (搖擺州), which is a curious direct borrowing from American election terminology. In the early post-Martial Law era, Taichung was referred to as a “desert of democracy” because while the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was winning elections in the north and south, Taichung remained staunchly loyal to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT). That changed over time, but in both Changhua and Taichung, the DPP still suffers from a “one-term curse,” with the

Jan. 26 to Feb. 1 Nearly 90 years after it was last recorded, the Basay language was taught in a classroom for the first time in September last year. Over the following three months, students learned its sounds along with the customs and folktales of the Ketagalan people, who once spoke it across northern Taiwan. Although each Ketagalan settlement had its own language, Basay functioned as a common trade language. By the late 19th century, it had largely fallen out of daily use as speakers shifted to Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese), surviving only in fragments remembered by the elderly. In

William Liu (劉家君) moved to Kaohsiung from Nantou to live with his boyfriend Reg Hong (洪嘉佑). “In Nantou, people do not support gay rights at all and never even talk about it. Living here made me optimistic and made me realize how much I can express myself,” Liu tells the Taipei Times. Hong and his friend Cony Hsieh (謝昀希) are both active in several LGBT groups and organizations in Kaohsiung. They were among the people behind the city’s 16th Pride event in November last year, which gathered over 35,000 people. Along with others, they clearly see Kaohsiung as the nexus of LGBT rights.