Taiwan in Time: Feb. 29 to Mar. 6

When the 228 Incident first broke out in 1947, the editorial in the government-owned Taiwan Shin Sheng Daily News expressed sympathy for the victims and criticized the Tobacco Monopoly Bureau for going after illegal cigarette vendors, who were trying to make ends meet, instead of cigarette smugglers.

It further condemned the use of force. “Taiwan is a peaceful place,” it stated. “There was no need for Tobacco Monopoly Bureau agents to carry guns with them.”

Photo: Han Cheung, Taipei Times

When this editorial was published, Shin Sheng was managed by Juan Chao-jih (阮朝日), a native of Pingtung who had been in the newspaper business since 1932. Of course, the editorial had to claim that the agents had violated governor-general Chen Yi’s (陳儀) “peaceful orders” before calling for their prosecution.

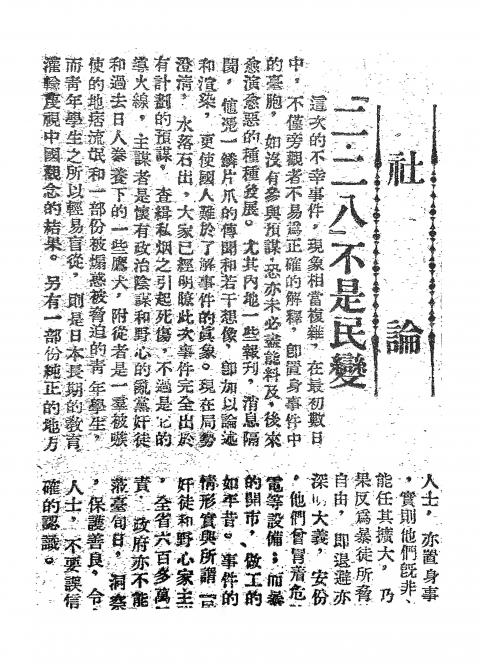

But an editorial published on March 28, titled 228 Was Not a Civil Uprising, has a completely different tone.

“The conspirators were scheming traitors with political ambition along with lackeys of the former Japanese government, and the followers were local hoodlums, gangsters and students who were either forced or provoked into participation,” it stated.

It could be explained that the newspaper became more cautious with its words with martial law declared on March 4 and other private newspapers being shut down and staff members arrested.

But rewind three days and look at March 25 edition, introducing the paper’s new management, both officials who arrived from China after World War II: general manager Mao Ying-chang (毛應章), a major-general with the Taiwan Garrison Command, and editor-in-chief Chang Kao (張?), an advisory officer at the Taiwan Provincial Administration Agency.

By that time, Juan, original deputy editor-in-chief Wu Chin-lien (吳金鍊) and several other staff members had already been missing for nearly two weeks.

After one last editorial on March 2, no more appeared until March 18, the newspaper having been reduced in size due to a “severe paper shortage.”

The paper’s shift in tone was already obvious in the March 18 editorial, which blamed the incident on Japanized Taiwanese and managers of newspapers that contained “various poisonous elements.”

“Some have had their minds poisoned by the remnants of the Japanese, while others are trying to spread communism in Taiwan,” it stated.

FORTY FIVE YEARS

One would think that a government paper would remain free of the nationwide newspaper purge. The paper did remain safe as far as being one of the few that were continuously published during the incident’s aftermath, but it was a different story for its staff.

Juan’s daughter, Juan Mei-shu (阮美姝) was 18 years old when her father was arrested on March 12. She remembers her father, who was bedridden with chronic asthma, refusing to flee when the purge began.

She says that he had done nothing wrong.

The younger Juan writes in her book on her father’s disappearance that she found it odd that the newspaper continued to operate as though nothing had happened after the disappearance of its two top editors.

She then spent the next 40-odd years searching for answers to her father’s disappearance. She writes that she even received a response from Chen Yi, stating that Juan was a very important person for Taiwan’s future and the government had no reason to arrest him.

In November 1991, Juan finally proved Chen Yi wrong as she found her father’s arrest files. He was accused of being a “main conspirator the 228 rebellion, using [his] newspaper for treacherous activities and using [his] newspaper to sow discord between soldiers and civilians.”

In a letter to her deceased father, Juan writes, “I’ll use this book to wipe clean the injustices you suffered, and I hope that when people read this book, they’ll know that the main conspirator was the government.”

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,