The largest ape to roam Earth died out 100,000 years ago because it failed to tuck into savannah grass after climate change hit its preferred diet of forest fruit, scientists suggest.

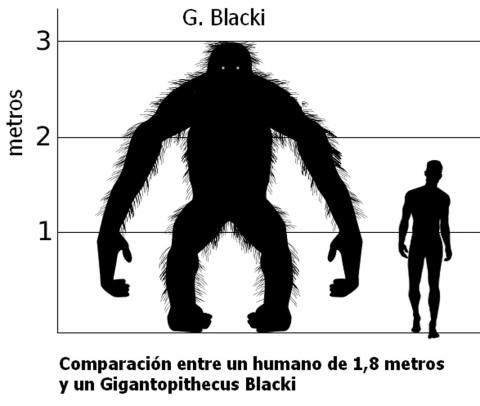

Gigantopithecus — the closest Nature ever came to producing a real King Kong — weighed five times as much as an adult man and probably stood 3m tall, according to sketchy estimates.

In its heyday a million years ago, it inhabited semi-tropical forests in southern China and mainland Southeast Asia.

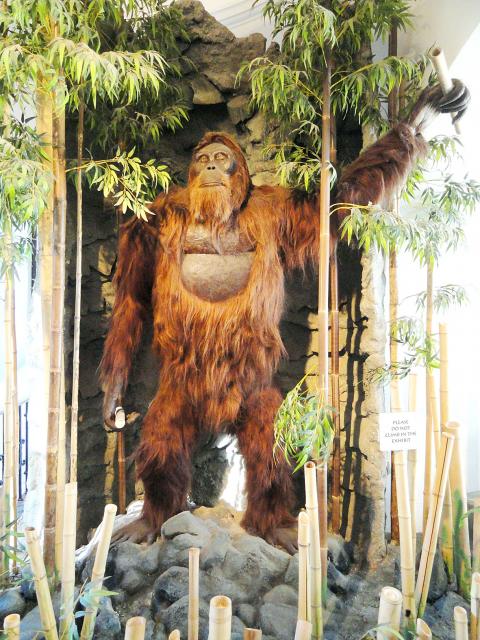

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Until now, though, almost nothing was known about the giant’s anatomical shape or habits. The only fossil records are four partial lower jaws, and perhaps a thousand teeth — the first of which turned up in the 1930s in Hong Kong apothecaries where they were sold as “dragon’s teeth.”

These meagre remains “are clearly insufficient to say if the animal was bipedal or quadrupedal, and what would be its body proportions,” Herve Bocherens, a researcher at T|bingen University in Germany, says.

Its closest modern cousin is the orangutan, but whether Gigantopithecus had the same golden-red hue, or was black like a gorilla is unknown. Another mystery: its diet. Was it a meat-eater or a vegetarian? Did it share a taste for bamboo with its neighbour the prehistoric giant panda?

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Answering this riddle might also tell us why a monster that surely had little to fear from other fauna went extinct.

ADAPT OR DIE

That’s where the teeth had a story to tell.

Examining slight variations in carbon isotopes found in tooth enamel, Bocherens and an international team of scientists showed that the primordial King Kong lived only in the forest, was a strict vegetarian, and probably wasn’t crazy about bamboo.

These narrow preferences did not pose a problem for Gigantopithecus until Earth was struck by a massive ice age during the Pleistocene Epoch, which stretched from about 2.6 million to 12,000 years ago.

That’s when nature, evolution — and perhaps a refusal to try new foods — conspired to doom the giant ape, Bocherens explained.

“Due to its size, Gigantopithecus presumably depended on a large amount of food,” he said.

“When during the Pleistocene, more and more forested area turned into savannah landscapes, there was simply an insufficient food supply.”

And yet, according to the study, other apes and early humans in Africa that had comparable dental gear were able to survive similar transitions by eating the leaves, grass and roots offered by their new environments. But for some reason, Asia’s giant ape — which was probably too heavy to climb trees, or swing in their branches — did not make the switch.

“Gigantopithecus probably did not have the same ecological flexibility and possibly lacked the physiological ability to resist stress and food shortage,” notes the study, which is to be published in a specialist journal, Quaternary International. Whether the mega-ape could have adapted to a changing world but didn’t, or whether it was doomed by climate and its genes, is probably one mystery that will never be solved. Climate change several hundred thousand years ago was also likely responsible for the disappearance of many other large animals from the Asian continent.

Growing up in a rural, religious community in western Canada, Kyle McCarthy loved hockey, but once he came out at 19, he quit, convinced being openly gay and an active player was untenable. So the 32-year-old says he is “very surprised” by the runaway success of Heated Rivalry, a Canadian-made series about the romance between two closeted gay players in a sport that has historically made gay men feel unwelcome. Ben Baby, the 43-year-old commissioner of the Toronto Gay Hockey Association (TGHA), calls the success of the show — which has catapulted its young lead actors to stardom -- “shocking,” and says

Inside an ordinary-looking townhouse on a narrow road in central Kaohsiung, Tsai A-li (蔡阿李) raised her three children alone for 15 years. As far as the children knew, their father was away working in the US. They were kept in the dark for as long as possible by their mother, for the truth was perhaps too sad and unjust for their young minds to bear. The family home of White Terror victim Ko Chi-hua (柯旗化) is now open to the public. Admission is free and it is just a short walk from the Kaohsiung train station. Walk two blocks south along Jhongshan

The 2018 nine-in-one local elections were a wild ride that no one saw coming. Entering that year, the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) was demoralized and in disarray — and fearing an existential crisis. By the end of the year, the party was riding high and swept most of the country in a landslide, including toppling the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in their Kaohsiung stronghold. Could something like that happen again on the DPP side in this year’s nine-in-one elections? The short answer is not exactly; the conditions were very specific. However, it does illustrate how swiftly every assumption early in an

Snoop Dogg arrived at Intuit Dome hours before tipoff, long before most fans filled the arena and even before some players. Dressed in a gray suit and black turtleneck, a diamond-encrusted Peacock pendant resting on his chest and purple Chuck Taylor sneakers with gold laces nodding to his lifelong Los Angeles Lakers allegiance, Snoop didn’t rush. He didn’t posture. He waited for his moment to shine as an NBA analyst alongside Reggie Miller and Terry Gannon for Peacock’s recent Golden State Warriors at Los Angeles Clippers broadcast during the second half. With an AP reporter trailing him through the arena for an