Taiwan in Time: Jan. 4 to Jan. 10

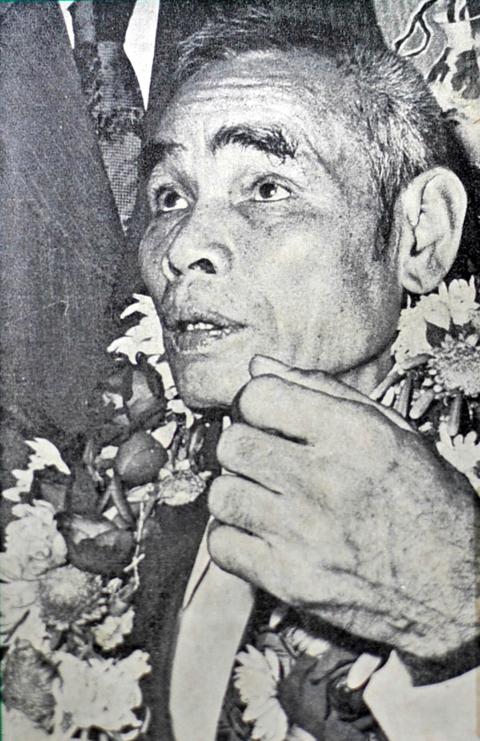

On Jan. 8, 1975, nearly 30 years after the end of World War II, former Imperial Japanese Army soldier Nakamura Teruo finally returned home.

It was a different place from what he had known. His native land was no longer part of Japan. His son, who was an infant when he left, was now a father of four children, and his wife had remarried. Everyone was calling him Lee Kuang-hui (李光輝) — a name he had never even heard of when he departed for Indonesia with the Takasago Volunteer Unit in 1944.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

A member of the Amis people, Western reports have his Aboriginal name as Attun Palalin, while local sources call him Suniuo, which is what this article will go with.

Even though the Takasago were a volunteer army in name, Suniuo says he was forced to enlist. Shortly after he landed on Morotai Island in Indonesia, the Allies arrived and secured it as a base. Suniuo lost contact with his group during this time.

Armed with an assault rifle, a helmet, knife, cooking pot and a mirror, Suniuo built a hut and remained in the jungle alone, surviving by hunting and farming. He did not know that the war had already ended, as the Japanese army declared him dead on Nov. 13, 1944.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Unsure of the situation outside of the jungle, Suniuo stayed hidden at all costs, cooking only in the dark so people wouldn’t see the smoke. In a first-hand account published shortly after his return titled Struggle in the Jungle for 30 Years (叢林掙扎三 十年), Suniuo recalls counting the days by the moon and recording each cycle by tying a knot in a rope. He says his upbringing in the mountains in relative poverty provided him the will and ability to survive for so long.

“I calmly stayed alive there,” he says. “Although I didn’t have anybody to talk to, buried deep in my heart seemed to be a glimmer of hope and expectation. The only trace of happiness during this time came from the fact that I was still alive and I hadn’t lost my sense of existence yet.”

As Suniuo’s only clothes deteriorated over time, he says he became used to being naked most of the time, only using a US Army jacket he found to cover himself at night.

Most of his time was devoted to finding food, he says. He grew sweet potatoes, beans, bananas and sugar cane in his garden, gathered roots and fruits and trapped boar, pheasant and other birds.

“Not to lose my life became my only goal, and that exhausted almost all of my time,” he says.

The only two forms of entertainment he had was fishing and fiddling with a home-made abacus. In order to keep himself from thinking of his family at home, he stayed busy exploring his surroundings and undertaking various improvement projects around his hut.

Suniuo says he made a grave error in assuming that war wasn’t over from the planes that flew by above him each day, only later to find out that it was because the jungle was near an Indonesian air force base. As aviation technology improved over time, planes became faster and sleeker, and Suniuo thought it was the result of an arms race between the two warring sides.

“I made one simple wrong judgment, and it cost me 30 years,” he says.

In November 1974, local reports surfaced of a “naked wild man” in the mountains, prompting the Indonesian army to send an expedition force, which, after 30 hours, found Suniuo chopping wood outside his hut.

This brought up the question of whether he should be repatriated to Japan or Taiwan. Suniuo was given the choice, and he chose his homeland.

According to this biography, his back pay as a soldier over 30 years only amounted to about NT$7,000. But after some commotion in the media, the Japanese government decided to give him over NT$380,000 instead. He later received various donations from Japanese, Indonesian and local sources.

Yet, a return after so long has to be bittersweet. His parents were dead, and only two siblings survived — all going by Chinese names now. Suniuo’s wife’s new husband (of more than 10 years) was originally willing to move out and let the couple reunite, but Suniuo decided not to disturb their life and bought an apartment nearby. Just four years after his return, he died of lung cancer.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

That US assistance was a model for Taiwan’s spectacular development success was early recognized by policymakers and analysts. In a report to the US Congress for the fiscal year 1962, former President John F. Kennedy noted Taiwan’s “rapid economic growth,” was “producing a substantial net gain in living.” Kennedy had a stake in Taiwan’s achievements and the US’ official development assistance (ODA) in general: In September 1961, his entreaty to make the 1960s a “decade of development,” and an accompanying proposal for dedicated legislation to this end, had been formalized by congressional passage of the Foreign Assistance Act. Two

Despite the intense sunshine, we were hardly breaking a sweat as we cruised along the flat, dedicated bike lane, well protected from the heat by a canopy of trees. The electric assist on the bikes likely made a difference, too. Far removed from the bustle and noise of the Taichung traffic, we admired the serene rural scenery, making our way over rivers, alongside rice paddies and through pear orchards. Our route for the day covered two bike paths that connect in Fengyuan District (豐原) and are best done together. The Hou-Feng Bike Path (后豐鐵馬道) runs southward from Houli District (后里) while the

March 31 to April 6 On May 13, 1950, National Taiwan University Hospital otolaryngologist Su You-peng (蘇友鵬) was summoned to the director’s office. He thought someone had complained about him practicing the violin at night, but when he entered the room, he knew something was terribly wrong. He saw several burly men who appeared to be government secret agents, and three other resident doctors: internist Hsu Chiang (許強), dermatologist Hu Pao-chen (胡寶珍) and ophthalmologist Hu Hsin-lin (胡鑫麟). They were handcuffed, herded onto two jeeps and taken to the Secrecy Bureau (保密局) for questioning. Su was still in his doctor’s robes at

Mirror mirror on the wall, what’s the fairest Disney live-action remake of them all? Wait, mirror. Hold on a second. Maybe choosing from the likes of Alice in Wonderland (2010), Mulan (2020) and The Lion King (2019) isn’t such a good idea. Mirror, on second thought, what’s on Netflix? Even the most devoted fans would have to acknowledge that these have not been the most illustrious illustrations of Disney magic. At their best (Pete’s Dragon? Cinderella?) they breathe life into old classics that could use a little updating. At their worst, well, blue Will Smith. Given the rapacious rate of remakes in modern