Taiwan in Time: Nov. 16 to Nov. 22

Having already been sentenced to death in absentia and with the Japanese colonial police closing in, Liao Tien-ting (廖添丁) still met an unexpected end in a cave in what is today New Taipei City’s Bali District (八里). On the run after a three-month crime spree, the most common version of events is that Liao was betrayed by his friend Yang Lin (楊林), who informed the police about Liao’s whereabouts. Liao tried to shoot Yang upon realizing the truth, but the bullet got stuck. Yang picked up a nearby hoe and crushed Liao’s skull. It was 1909, and Liao was 26 years old.

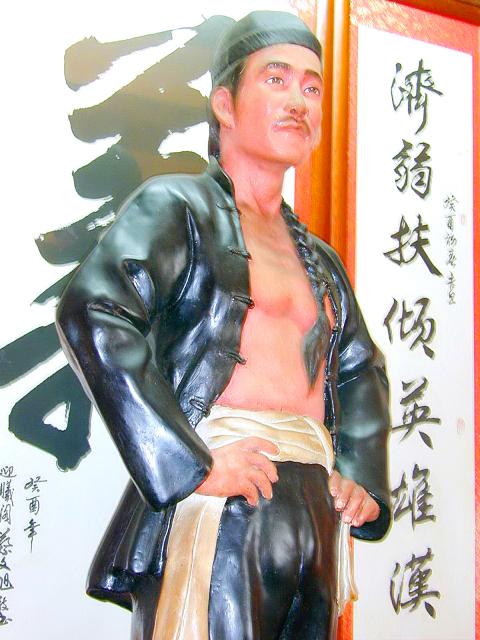

There are probably as many versions of Liao’s death as there are of his life and legacy, and even the day of his death, Nov. 18, is disputed. After all, who knows what’s real or not about this anti-Japanese folk hero — often considered Taiwan’s Robin Hood — whose story has been adapted into countless children’s books, novels, television programs and even an orchestral suite and Cloud Gate Dance Theatre (雲門舞集) performance. He’s worshipped at the Liao Tien-ting Temple (廖添丁廟) in Bali — which also houses his grave — and in other places such as the Xia Hai City God Temple (霞海城隍廟) in Taipei.

Photo: Ou Su-mei, Taipei Times

Even the story about his gravestone is legendary. It’s said that shortly after Liao’s death, the wife of a Japanese officer who pursued Liao became ill. Desperate to seek a cure, the officer followed local advice to pray at Liao’s burial place and his wife recovered soon after. The officer then erected the gravestone and worshipped Liao as a foster son.

In July this year, the Taipei District Court displayed for the first time a verdict sentencing Liao to death for the killing of alleged police informant Chen Liang-chiu (陳良久), even though Liao died before he could be arrested. To the Japanese at that time, he was no more than a robber and murderer, but to Taiwanese it was a completely different matter.

According to the Taiwan Daily News (台灣日日新報), a newspaper published during the Japanese colonial era, people visited and prayed at Liao’s grave regularly, believing that as a ghost he could cure sickness and perform other miracles. A January 1910 article stated that there was no more space in front of the grave to place joss sticks. The Japanese banned the practice in March that year, but Liao’s legend simply kept growing as an yizei (義賊, righteous criminal) who fought against colonial injustice by robbing the rich and giving to the poor.

Photo: Chang Jui-chen, Taipei Times

His heroic deeds and extraordinary abilities are still celebrated today, as a children’s book published in 2008 depicts some of Liao’s most famous moments, including saving an old man from police brutality with the throw of a pebble, robbing a man who made his fortune by colluding with the Japanese, jumping out of windows, flying over roofs and disguising himself as an old lady while being pursued. Other books show Liao being involved in anti-Japanese organizations, one even stating that both his parents were killed in a Japanese invasion of their village.

Born in today’s Taichung in 1883, Liao was 12 years old when Taiwan became part of Japan. His household registry shows that he was sentenced in 1902 to 10 months and 15 days in prison for larceny, his third offense. Some say he was locked up between 1905 and 1909 for his fifth offense, and others say he continued committing minor robberies and thefts during that time.

Liao’s final spree began in July 1909, including an incident on Aug. 20 where he and several accomplices stole guns, ammunition and a sword from two police dormitories. He also killed Chen during this time, frequently making headlines as the man who just could not be caught. After committing his final string of robberies in early November, Liao fled to the cave where he ultimately met his end.

That’s all that is certain about Liao’s life; the rest probably grew out of embellishments by locals, who reconstructed Liao as a spiritual hero to ease their frustration against their colonial masters — after all, who doesn’t like stories where the oppressors are terrorized?

Historian Tsai Chin-tang (蔡錦堂) says that Liao’s legendary abilities are mostly likely rooted in newspaper reports detailing his elusiveness, including how he jumped out of a moving train, fell into a valley and survived.

After his death, Liao made headlines a few more times, including one about people claiming to have seen his ghost. His crime spree was also adapted by a Japanese playwright in 1911.

As to the story that he was Taiwan’s Robin Hood, there is no concrete evidence that Liao gave his loot to the poor. But as early as 1914, a Taiwanese opera script about Liao was published, already bearing the “righteous outlaw” moniker.

After the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) took over Taiwan, Liao’s image transformed once more — this time into an anti-Japanese hero. But things didn’t stop there, as he was well on the road to deification.

There had already been many supernatural tales about Liao, including the one with the Japanese officer and others about his spirit appearing here and there to administer justice. People at that time believed that if a vigorous person died, he would become a powerful ghost, and started praying at his grave for various reasons, including health and fortune. Another belief was that someone who died a violent or unnatural death would become a ligui (厲鬼, vengeful ghost) and must be pacified through worship.

Liao’s grave was rebuilt after the Japanese left and worshipping resumed. Interest in Liao grew after a feature film was made about his life in 1956, and a small shrine was built around his resting place in 1958.

Locals tried to expand the temple with Liao as the main deity in the 1970s, but the government rejected the proposal due to lack of historic evidence of his heroic deeds. The temple was still built, but with Guan Gong (關公), also a real-life hero-type, as the main deity and Liao as secondary. Nevertheless, most people refer to it as the Liao Tien-ting Temple, and with its completion in 1975, Liao had completed his journey from wanted criminal to a worshipped deity.

Taiwan in Time, a column about Taiwan’s history that is published every Sunday, spotlights important or interesting events around the nation that have anniversaries this week.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

The other day, a friend decided to playfully name our individual roles within the group: planner, emotional support, and so on. I was the fault-finder — or, as she put it, “the grumpy teenager” — who points out problems, but doesn’t suggest alternatives. She was only kidding around, but she struck at an insecurity I have: that I’m unacceptably, intolerably negative. My first instinct is to stress-test ideas for potential flaws. This critical tendency serves me well professionally, and feels true to who I am. If I don’t enjoy a film, for example, I don’t swallow my opinion. But I sometimes worry