English-language cookbooks featuring specifically Taiwanese food are a rarity — a search on Amazon.com yields just four entries, three of them published within the past three years.

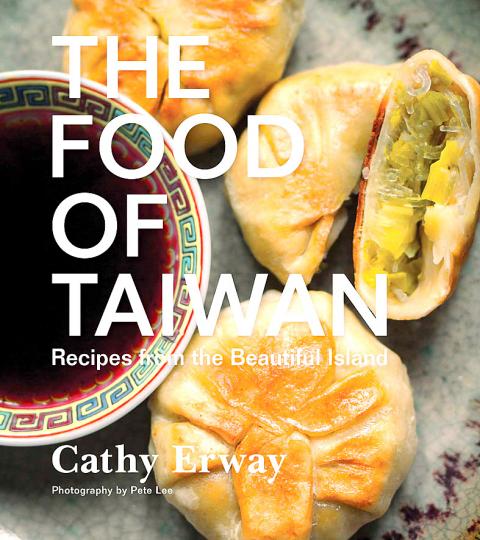

The most recent one, The Food of Taiwan: Recipes from the Beautiful Island, is an effort by New York City-based food writer Cathy Erway, whose mother is Taiwanese.

Erway’s previous book, The Art of Eating In contains more than just recipes — it’s a memoir that chronicles the two years she swore off restaurants. Her latest effort is similar — before delving into mouth-watering favorites such as beef noodle soup and pork belly buns, she talks about her personal connection to Taiwan and provides background information on the country. Even through the recipes section, she gives tidbits of information to allow the reader to better understand the various influences that have shaped Taiwan.

NATIONAL CUISINE?

It’s hard not to mention the meaning and definition of Taiwanese identity in any book introducing the country. This is brought up as early as the foreword by fellow food writer and Taiwanese-American Joy Wang.

“The issue of national identity in Taiwan is oftentimes fraught with caveats,” Huang writes. “While explaining all of that is cumbersome, the awareness of those caveats means that for many, even those of us who never grew up in the country, history is always close at hand.”

Erway begins her story in March 2004 when she witnesses the mass protests in front of the Presidential Office Building two days after president Chen Shui-bian (陳水扁) was re-elected.

She recalls being handed a fried pork bun (水煎包) and wondering how good protest-rally food could be.

“Of course it was good — this was Taiwan,” she writes.

Taiwanese cuisine left a deep impression on Erway, who found that most of her experiences in the country included food. Through her stay in Taiwan, she also learned about what makes her mother’s homeland a unique place.

Erway tries to stay impartial in explaining the political situation of Taiwan, as she says she has no strong political beliefs.

For example, she writes, “Is China Taiwan’s founding father or ultimate foe? A bullish presence and insult to democratic agendas, or a great economic opportunity and cultural kin? Who am I to say?”

Despite the political tension and identity issues, Erway says she noticed a growing sense of Taiwanese pride. Yet is there a unified culture? What exactly is Taiwanese cuisine?

While Erway explores the answer through the book, she says she sees the book as “only the beginning of a larger dialogue” of an “endless and ever expanding topic” as Taiwanese food continues to evolve.

HISTORY OF TAIWAN

The next few chapters provide brief but informative overviews of various aspects of Taiwan’s past and present, interspersed with scenic and vibrant photographs by Pete Lee.

The history section is comprehensive and thorough, yet Erway mistakenly describes the 228 Incident as resistance to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) “invasion” of Taiwan in 1947. In fact, the KMT had ruled Taiwan since 1945, and the incident was a violent government suppression of a local uprising.

But enough of that. Food is the main topic here.

Erway says she focuses on dishes that use ingredients that can be found in America, or can be easily substituted. This makes sense on one level, making the cuisine more accessible, but also runs the danger of being inauthentic.

It turns out, however, that the substitutions are mostly harmless — using cornstarch instead of sweet potato starch (though, if available, she calls the latter a “secret weapon for perfecting Taiwanese cuisine,”) Italian basil in place of its Asian counterpart and Japanese sake in place of Taiwanese rice wine.

Recipes

The recipes, which begin with appetizers and street snacks and end with desserts, are straightforward and easy to follow, and include background information about the origins of the dish.

For example, Erway mentions how chili sauce with Sichuan peppercorns didn’t become popular in Taiwan until the Chinese came in the mid-1990s, Hakka influences on pork belly buns and the Hokkien origins of oyster omelets (蚵仔煎). There are purely Taiwanese inventions — such as coffin bread (棺材板), that make use of foreign ingredients such as white bread. She discusses how beef noodle soup is believed to have originated in military dependants villages (眷村) and the Aboriginal practice of steaming sticky rice in bamboo logs. We start to see why it is so hard to define Taiwanese cuisine, or culture, as a whole.

In between entries, Erway continues her exploration with entries such as an overview of the country’s night market culture and post-1949 Chinese influences on local cuisine as well as musings on the definition and appeal of the texture Taiwanese refer to as “Q” (“springy and bouncy”) and why stinky tofu is unsuitable to make in a home kitchen. Unfortunately, due to the organization of the book, these entries may be easy to overlook if one is simply looking for recipes and not flipping through the book in its entirety.

Overall, despite its billing as a cookbook, The Food of Taiwan never becomes a pure list of recipes, and readers will learn about the author’s connections and feelings toward her maternal homeland and gain a deeper understanding of what makes Taiwan what it is.

If you just want to use it as a cookbook, though, it’s still a wonderful resource.

A vaccine to fight dementia? It turns out there may already be one — shots that prevent painful shingles also appear to protect aging brains. A new study found shingles vaccination cut older adults’ risk of developing dementia over the next seven years by 20 percent. The research, published Wednesday in the journal Nature, is part of growing understanding about how many factors influence brain health as we age — and what we can do about it. “It’s a very robust finding,” said lead researcher Pascal Geldsetzer of Stanford University. And “women seem to benefit more,” important as they’re at higher risk of

Eric Finkelstein is a world record junkie. The American’s Guinness World Records include the largest flag mosaic made from table tennis balls, the longest table tennis serve and eating at the most Michelin-starred restaurants in 24 hours in New York. Many would probably share the opinion of Finkelstein’s sister when talking about his records: “You’re a lunatic.” But that’s not stopping him from his next big feat, and this time he is teaming up with his wife, Taiwanese native Jackie Cheng (鄭佳祺): visit and purchase a

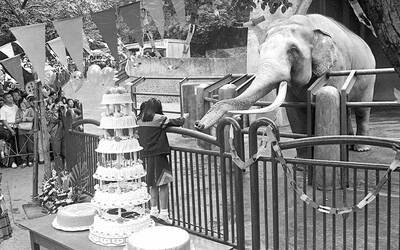

April 7 to April 13 After spending over two years with the Republic of China (ROC) Army, A-Mei (阿美) boarded a ship in April 1947 bound for Taiwan. But instead of walking on board with his comrades, his roughly 5-tonne body was lifted using a cargo net. He wasn’t the only elephant; A-Lan (阿蘭) and A-Pei (阿沛) were also on board. The trio had been through hell since they’d been captured by the Japanese Army in Myanmar to transport supplies during World War II. The pachyderms were seized by the ROC New 1st Army’s 30th Division in January 1945, serving

Mother Nature gives and Mother Nature takes away. When it comes to scenic beauty, Hualien was dealt a winning hand. But one year ago today, a 7.2-magnitude earthquake wrecked the county’s number-one tourist attraction, Taroko Gorge in Taroko National Park. Then, in the second half of last year, two typhoons inflicted further damage and disruption. Not surprisingly, for Hualien’s tourist-focused businesses, the twelve months since the earthquake have been more than dismal. Among those who experienced a precipitous drop in customer count are Sofia Chiu (邱心怡) and Monica Lin (林宸伶), co-founders of Karenko Kitchen, which they describe as a space where they