Above Hell’s Valley in Taipei’s Beitou District (北投區), there’s a clearing where, when the steam dissipates, you can watch tourists circling the volcanic cavity, selfie-sticks waggling like cockroach antennae.

Beitou invites pathetic fallacy. The name derives from the Ketagalan for “witch,” the area evoking a bubbling cauldron. Prospecting for sulfur in 1696, Qing Dynasty official Yu Yonghe (郁永河) described “a big pot in which we are walking on the lid.” Two centuries later, George McKay noted the “hiss and roar.” But these growls hide whispers.

Opposite the hole in the foliage, for example, a distinctive building with a facade of blue wooden slats has long held its peace. Until recently, the story behind this location was suffocated by an obfuscation that even the dense sulfur clouds couldn’t match.

Photo: yang yuan-ting, Taipei Times

clandestine operation

For 30 years, 144 Wenquan Road (溫泉路) was the headquarters of the White Group (白團), a clandestine team of Japanese military advisers to the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government. Now, thanks to the probing of a Japanese journalist, this startling episode of modern Taiwanese history has been laid bare.

For the KMT, the White Group ranks among the dirtiest of rags in an already overflowing basket of soiled laundry, and given the virulently anti-Japanese bent that some of the program’s graduates later assumed, their reticence to see the truth revealed is understandable.

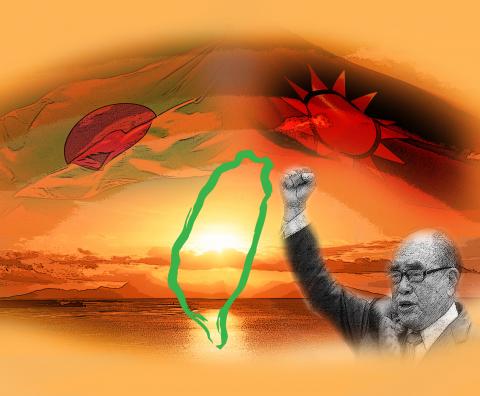

illustration: kevin sheu

In January, Nojima Tsuyoshi, editor of the Chinese-language digital version of the Japanese daily Asahi Shimbun, published Last Empire Soldiers: Chiang Kai-shek and the White Group (最後的帝國軍人:蔣介石與白團), an account of the team’s time in Taiwan.

Covert Japanese assistance to the KMT in Taiwan began in 1949 when Chiang Kai-shek (蔣介石), whose forces had just fled China after losing the civil war, enlisted the services of Lieutenant General Nemoto Hiroshi to repel the communist advance on the outlying island of Kinmen.

Hiroshi’s tactics, which included allowing the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) forces to land so they could be ambushed and nixing a KMT proposal to burn down villages where PLA soldiers had holed up, undoubtedly saved the KMT’s bacon. With the smoke barely cleared, KMT General Hu Lien (胡璉) swanned in to claim the victory. He was nowhere near Kinmen during the action.

While General Keh King-en (葛先才), the leader of an advance party to Taiwan, was publicly berating the nipponized Formosans for being a “degraded people,” Chiang was taking a much more pragmatic tack. In forming the White Group, he sought out top Japanese talent, offering benefits and hefty remuneration.

During the Japanese colonial era, a posting to Taiwan was considered an unenviable drag, but with postwar public sentiment in Japan now against senior military figures and employment hard to come by, Nojima says the White Group personnel looked on their Taiwan adventure as an opportunity.

the japanophile

The Generalissimo had a soft spot for the Japanese. Over the years, this had earned him the scorn and suspicion of party hardliners. Chiang spent six years in Japan, served in the Imperial Japanese Army from 1909 to 1911 and spoke the language. Well aware that Japanese military know-how was a cut above what the KMT officer class had to offer, he was keen to make use of skilled ex-officers. Of course, he wasn’t about to advertise the fact.

As Nojima writes, it wasn’t just about a loss of face. Chiang could ill-afford to have the Americans offside and once the US made it clear that they were not happy with the arrangement, it was conducted in the shadows. Still, it was made just visible enough to provide leverage whenever American assistance wasn’t forthcoming.

Barak Kushner, who has written and spoken extensively on the White Group and the KMT’s complicated ties with Japan, sees the relationship as a marriage of convenience.

“Both [the KMT and Japan] essentially had become pariahs in their own region and their sole means of salvation was ironically in some measure to link up with each other,” Kushner says.

Although the alliance was informed by pragmatism on both sides, Kushner believes that there were other motivations at play.

“Perhaps the idea of pan-Asianism, which certainly was rife in higher KMT circles, many of whom studied in Japan prewar, still remained,” he says.

At the same time, Kushner says that the KMT had to look to all quarters for support. “Many would ask what other choice they had when US support looked desperate and Taiwan was considered a backwater.”

The White Group’s initial 17-man team was smuggled into Taiwan via Hong Kong in 1949. Participants were given Chinese noms de guerre, with the group named after its leader, Tomita Naosuke, who assumed the moniker Pai Hung-liang (白鴻亮). A former major general, Taiwan’s “Mr. White” was well known to Chiang having assisted KMT forces in the final throes of the civil war.

military legacy

Although the group’s remit was largely advisory, it is credited with introducing reserve officer exams and close combat techniques. Overall, at least 10,000 soldiers were trained under the group’s guidance.

At the behest of the US Military Assistance Advisory Group, the White Group was officially disbanded in 1959, though limited operations continued for years after. Tomita was persuaded to remain in Taiwan and was eventually made an honorary Republic of China general, the only foreigner to achieve this distinction.

Tomita continued to live at the house on Wenquan Road until his death in 1979 during a visit to Japan. At his request, his ashes were divided between his homeland and Taiwan. The latter portion of his remains can be found at Haiming Temple (海明寺) in Shulin District (樹林) in New Taipei City where they were placed by Chiang’s adoptive son Chiang Wei-kuo (蔣緯國).

The house at Wenquan Road is currently undergoing renovation. A spokesperson for the Beitou District Office confirmed that the property is now privately owned and unlikely to be open to the public any time soon.

However, early last year, a Japanese tour group, which included relatives of White Group officers, visited the location to mark the 35th anniversary of Tomita’s death. Tomita’s son expressed his pleasure that the historical record had finally been set straight.

raging against the japanese

Some people see things differently. In September last year, former Premier Hau Pei-tsun (郝柏村) addressed a seminar marking the 70th anniversary of Japan’s surrender. As reported in this newspaper, the aim of the event was to “debunk the lies fabricated by the Japanese bandits’ slaves who overstayed in Taiwan (滯臺倭奴) and who have distorted the real history.”

It was just the latest in a long line of anti-Japanese tirades by the 95-year-old Hau. A couple of months later, former vice president Lien Chan (連戰) was at it, branding Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je’s (柯文哲) family “traitors” for adopting Japanese names when Japan ruled over Taiwan.

These race-card rants by KMT old timers are fairly standard. Yet, as has been pointed out, Lien’s comments are more than a little rich, given the pro-Japanese leanings of his grandfather, the historian Lien Heng (連橫).

One might also expect a little more circumspection from Hau. As one of the White Group’s most illustrious alumni, the four-star general was on intimate terms with the Japanese during a period when ordinary Taiwanese faced persecution for perceived Japanese proclivities.

Nojima has revealed that during his research he made three separate requests for an interview with Hau. On each occasion his correspondence went unanswered. This is hardly surprising. Coming clean now would expose the hypocrisy of a stance that has become an article of faith.

For all the harping about the importance of “true history,” the KMT has always been selective about what that history should include. For Hau and his ilk, the details of what went on behind the doors of 144 Wenquan Road is best left shrouded in Beitou’s mists.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of