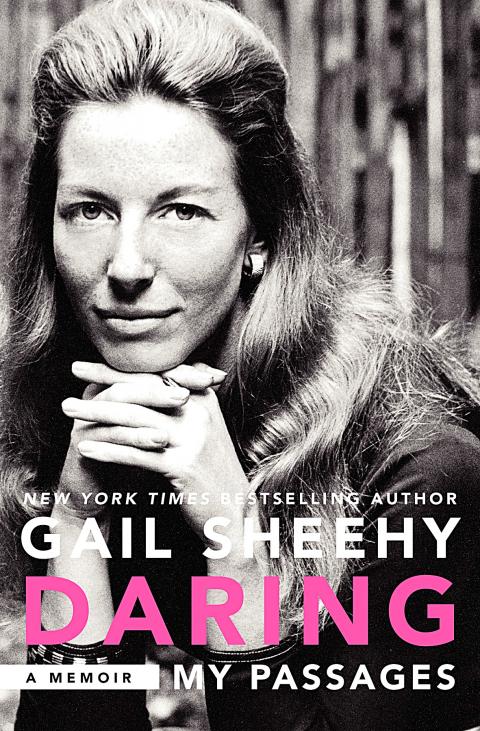

Gail Sheehy’s memoir is extremely effusive, mostly about herself. Some of that takes the form of writerly self-congratulation. Some attests to her wild sexual allure. Some consists of exaggerated claims for the importance and originality of her work. And the worst involves editorial choices that could easily have been avoided. Memoirists, you need not include every flattering remark that anyone ever made about you, even in the interest of full disclosure.

Yet Sheehy’s Daring: My Passages reprints (to cite just one of endless examples) this letter to her second husband, magazine editor Clay Felker, from his previous wife, actress Pamela Tiffin. It was written during the long, bumpy period between when Felker and Sheehy, who was working for him, began a secret romance in 1968 — kissing over raw copy of her article about Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination, of all things — and when they finally married in 1984. The occasion was one of their many breakups.

“I hear that you have stopped seeing Gail Sheehy,” wrote Tiffin, who is mentioned only glancingly in the book. “Don’t be foolish. She is a woman of fine character and great talent. Be good to her.”

So “Kudos” might have worked as a Sheehy memoir title, too. That Passages part is mostly shoehorned in just as a branding device. Anyone drawn to this book will already have learned more than enough about the chirpily named “passages” devised by Sheehy to remove dated, negative connotations from aging and putative loss.

She was right about a lot of them: Even though her original 1976 book, Passages, did not envision life beyond the mid-50s, the protean Sheehy has reinvented herself, reshaped her life and kept on writing well into her 70s. (Felker died in 2008 at 82.)

For a book this fulsome and detailed, Daring is surprisingly unrevealing. Sheehy devotes a lot of attention to her career arc, first describing herself as a hippie waif from the Lower East Side. One of her best early anecdotes involves covering the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi for Cosmopolitan, during which she had to endure not only being called Pussycat by the magazine’s editor in chief, Helen Gurley Brown, but having also to overpay for the privilege of receiving her mantra.

“Forty-five years later, I think I am reasonably safe in revealing” those secret syllables, she writes. It was just “Shee-Om,” which sounded suspiciously like a none too mystical hitching of her last name to a sacred sound.

She writes of herself working, ever adorable, at the brand-new offices of New York magazine (“my skirts were short enough to reveal my blued knees”) and reels off a full list about the talent Felker gathered for the magazine. Expect some crazily mixed metaphors: Milton Glaser, the art designer who was a huge reason for the publication’s instant impact, is described as “the son of a tailor marinated in the knish culture of the Bronx.” As an overwrought stylist, Sheehy has not changed, nor has she lost her tendency to fawn. Judging from this book, she never met a powerful editor without immense charm and a brilliant mind.

But the king of the realm was Felker, who let her enter his rarefied world in a torrid yet halting way. “My emotions move with glacial slowness,” he once told her. Those few words say more than chapters’ worth of her own circular reasoning about why they had such approach-avoidance problems. But she moved abruptly into his palatial uptown apartment with Maura, her daughter by an early first marriage. And they were one small, happy family, except for the times when they were not. Sheehy did her hippie best to play hostess to guests including Henry A. Kissinger, who was definitely not her type. Felker did enough conspicuous flirting to drive her out of the domestic arrangement, a passage that she now, typically, sees as a daring, brave leap forward that she needed to take in order to gamble on their future happiness.

Sheehy puts the best possible face on the fact that she did her most sensationalistic work under Felker’s tutelage. One of the pieces for which she will always be best remembered is “Redpants and Sugarman,” about a streetwalker and a pimp, for which she dressed up as a prostitute to do her reporting. (New Journalism at work: She begins the chapter on this by quoting Felker as exclaiming, “You’re going out in that?!”)

Never mind that she sent a confusing message by appearing in whore’s mufti while carrying a cassette recorder; never mind that she patiently passes this off as “saturation reporting,” a journalistic practice that has since become commonplace, even though her get-up reeked of oversaturation. The truth is that Sheehy made up characters for this piece but acknowledged that in a disclaimer. Then Felker, to her everlasting horror, took out the disclaimer because he thought it slowed down the article. She landed in a heap of trouble for what still qualifies as a serious ethical breach.

Other parts of “Daring” cite Sheehy’s favorite Vanity Fair profiles (hers, of course), written to armchair-psychoanalyze world leaders; her adoption of a second daughter, a Cambodian refugee whose arrival managed to make Felker feel like a displaced child; the bitter story of how Felker lost control of New York magazine after a hostile takeover by Rupert Murdoch, a deep heartbreaker in the annals of publishing history; and, more entertainingly than you might expect, the story of how Sheehy discovered that menopause could be a gold mine.

When she wrote “The Silent Passage” on that subject, she had no idea that she would get such a strong response from women who had not seen it addressed in a reader-friendly book before. Nor did she guess how uneasy it would make male interviewers.

“Menopause,” one Cleveland midday newscaster said to her. “Is that like — impotence?”

“Um, no,” she said awkwardly. But she eventually figured out a better answer: “Baldness. Is that like — Alzheimer’s?”

Dec. 16 to Dec. 22 Growing up in the 1930s, Huang Lin Yu-feng (黃林玉鳳) often used the “fragrance machine” at Ximen Market (西門市場) so that she could go shopping while smelling nice. The contraption, about the size of a photo booth, sprayed perfume for a coin or two and was one of the trendy bazaar’s cutting-edge features. Known today as the Red House (西門紅樓), the market also boasted the coldest fridges, and offered delivery service late into the night during peak summer hours. The most fashionable goods from Japan, Europe and the US were found here, and it buzzed with activity

During the Japanese colonial era, remote mountain villages were almost exclusively populated by indigenous residents. Deep in the mountains of Chiayi County, however, was a settlement of Hakka families who braved the harsh living conditions and relative isolation to eke out a living processing camphor. As the industry declined, the village’s homes and offices were abandoned one by one, leaving us with a glimpse of a lifestyle that no longer exists. Even today, it takes between four and six hours to walk in to Baisyue Village (白雪村), and the village is so far up in the Chiayi mountains that it’s actually

These days, CJ Chen (陳崇仁) can be found driving a taxi in and around Hualien. As a way to earn a living, it’s not his first choice. He’d rather be taking tourists to the region’s attractions, but after a 7.4-magnitude earthquake struck the region on April 3, demand for driver-guides collapsed. In the eight months since the quake, the number of overseas tourists visiting Hualien has declined by “at least 90 percent, because most of them come for Taroko Gorge, not for the east coast or the East Longitudinal Valley,” he says. Chen estimates the drop in domestic sightseers after the

US Indo-Pacific Commander Admiral Samuel Paparo, speaking at the Reagan Defense Forum last week, said the US is confident it can defeat the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in the Pacific, though its advantage is shrinking. Paparo warned that the PRC might launch a “war of necessity” even if it thinks it could not win, a wise observation. As I write, the PRC is carrying out naval and air exercises off its coast that are aimed at Taiwan and other nations threatened by PRC expansionism. A local defense official said that China’s military activity on Monday formed two “walls” east