Huang Ming-chuan (黃明川) is a man of many titles. He has been a painter and a photographer, but is best known as a filmmaker who Taiwanese media have described as a “lunatic.” The epithet was the result of his extreme method of filmmaking, which has drawn attention since he made his feature debut with The Man from Island West (西部來的人) in 1989. For the film, Huang scraped together a small budget from personal savings and loans from friends, assembled a tiny crew that was young and inexperienced but eager to work and learn, and ventured into the rugged mountain ranges and seaside cliffs of eastern Taiwan to tell the story of a member of the Atayal (泰雅) tribe returning to his village after years of living in Han-Chinese society.

The film’s atmospheric, poignant style caught the attention of the Golden Horse Awards (金馬獎) that year and generated heated discussion on Huang’s pioneering mode of filmmaking.

Within a decade, the director completed two more feature films that stand out for their ruminative themes and distinctive cinematic aesthetics, which were born out of his budgetary constraints. Bodo (寶島大夢, 1993) looks at the absurdity of Taiwan’s authoritarian past through the eyes of a low-ranking soldier, while the use of political and religious iconography in Taiwan is studied in Flat Tyre (破輪胎, 1998), in which two documentary filmmakers trek across the country to record public statues on film.

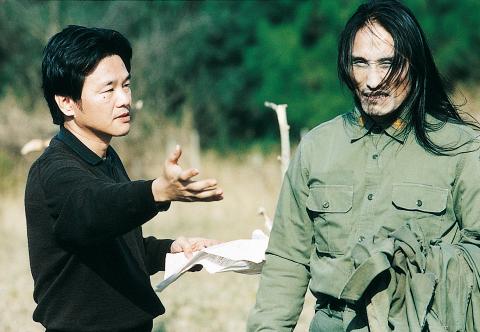

Photo courtesy of Formosa Filmedia Co

Clearly, Taiwanese history and culture have played essential parts in Huang’s works, even when the artist was living the American dream as a successful commercial photographer in New York City during the 1980s.

Born and raised in Chiayi City, Huang was determined to become a painter when he moved to New York after graduating from National Taiwan University’s (國立台灣大學) College of Law. But soon the aspiring young artist found himself more attracted to “pictures that move.” After learning from his friend Ang Lee (李安) just how expensive studying filmmaking at New York University was, however, Huang chose a cheaper option and entered the photography department at the Art Center College of Design in Pasadena, California. Four semesters later, Huang was back in the Big Apple, quickly building up a career in commercial photography.

When the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) government lifted martial law in 1987, Huang decided it was time to go back. Before he returned, the photographer wrote a book on the history of photography in Taiwan dating back to the Qing Dynasty and the Japanese colonial era.

Photo courtesy of Formosa Filmedia Co

“Around the time when Taiwan’s martial law was lifted, the country was driven by a strong desire to open up to the world and become a more just society,” the 56-year-old filmmaker said in an interview with the Taipei Times earlier this month. “To many, it was also a time to search for one’s roots.”

For the book, Huang spent more than three months flipping through archives at the Library of Congress in Washington, DC, and Harvard-Yenching Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“I’m always interested in Taiwan’s history before the island of Formosa became Sinified,” he said.

Photo courtesy of Formosa Filmedia Co

Huang stressed that The Man From Island West is not merely about Taiwan’s Aborigines and their cultural predicament, but is also related to all people who leave home to seek a better life and yet keep seeking the answers to questions like “Who am I?” and “Where do I come from?”

The director says he tries to forge a distinctly “Taiwanese” description of the land in his fictional works. Almost 20 years ago, before movies like Island Etude (練習曲) attempted to show different facets of the country and its people, Huang captured an image of the wild seaside landscape of eastern Taiwan, highlighting its rugged gorges, unforgiving mountains, and the deserted homes that were common in the countryside.

“Back then Taiwanese new wave cinema started to look back on declining villages and urban alienation. Taiwan’s first dwellers, the Aborigines, didn’t come into the picture. Later, local films gradually concentrated on urban settings, and no one cared about the different landscapes that make up the rest of the country. I feel that in order to explore another vision of Taiwan, you must leave Taipei and sanheyuan (三合院, a traditional architectural style for Han-Chinese family houses),” Huang said. “Just like being American does not have to be about cowboys. It can be in a space ship. It is a sense of belonging and does not have to take place in a location you are familiar with.”

Photo courtesy of Formosa Filmedia Co

Huang said that if The Man From Island West is a cinematic digestion of past readings, thinking and experiences, then Bodo vividly reflects how he felt after returning home and “setting foot on the land.”

To many, the period immediately after the lifting of martial law was an extraordinary moment in history, which Huang captures in Bodo by creating a dreamlike world inhabited by sadistic captains, vagabonds, deserters and a wandering ghost.

“Looking back at that time, I sometimes wonder if it actually happened or it was just a dream ... I want to tackle the collective experience in a surreal way in order to be true to those feelings it evokes,” Huang said.

Flat Tyre ruminates on the connection between the fall of Taiwanese political icons and the rise of religious ones. At the same time it pokes fun at its creators — director Huang and his crew — by depicting two documentary makers as Don Quixote types who cling to their beliefs no matter what.

In real life, Huang’s small team helped to train a group of now distinguished filmmakers including cinematographer Tseng Hsien-chung (曾憲忠) and directors Shen Ko-shang (沈可尚), Singing Chen (陳芯宜) and Zero Chou (周美玲).

In 1999, poet and art critic Chang Te-pen (張德本) wrote an article about Huang’s three feature films, calling them his “myth trilogy” — Aboriginal myth, military myth and political-religious myth. Chang concluded that the trilogy reflects the auteur’s attempt to come to terms with a society and culture in transition.

Yet Huang’s interest in the fleeting moments of history goes beyond the fictional realm. Since the early 1990s, he has made a considerable number of nonfictional works about Taiwan’s contemporary artists, writers and poets, and unlike many members of the YouTube generation, Huang takes time to shape his works. Most of the documentary projects take at least five or six years to complete. Some last a decade, like the monumental project for which 100 Taiwanese poets were invited to speak of their lives and art, and Avant-Garde Liberation: The Huang Ming-chuan Image Collection of the 1990s (解放前衛-黃明川九○年代的影像收藏), a series in 14 episodes about artists and the blooming of the contemporary art scene in the 1990s.

Huang says that his devotion to preserving history through nonfictional projects is spurred by his experience at the Library of Congress, where he was blown away by the colossal amount of archives of interviews with former slaves and their descendants.

“I deeply feel that being civilized is not as simple as minding one’s manners on the street. It means modernizing knowledge, accepting one’s history, putting it in order, making it accessible and allowing future generations to understand who we are,” he said.

A new direction in his filmmaking career began after the respected artist completed his stint as chairman of the National Culture and Arts Foundation (國家文化藝術基金會) last year. Huang said he now feels that anything is possible, and while continuing to work on several ongoing documentary projects, he has started a script for a feature film.

When asked about recent developments in Taiwanese cinema, Huang said teenage audiences and villagers had become more important to filmmakers. “Nowadays people go back to their home towns to encourage fellow villagers to see their movies. That could never have happened in the 1990s. It shows that there is a close relation between Taiwanese movies and Taiwanese society,” Huang said.

Thinking of box-office successes such as Seven Days in Heaven (父後七日) and Night Market Hero (雞排英雄) and their approach to grassroots identities and characters, it’s easy to agree with Huang that the filmmaking zeitgeist has changed.

“The 1990s was a time for self-examination and reflection. There were lots of innovative social activities, and people were propelled to reach out and explore while reviewing the past. Few people do such things now,” he said.

Whether or not the director will continue his signature mode of independent filmmaking remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: Women will play a far more significant role in his next feature film than men.

“Unlike the men in my past films who are confused and uncertain, women are always more positive and affirming ... I think it is time for them to stand out,” the director said.

A DVD box set of Huang’s original trilogy was recently released with the inclusion of an accompanying book and the director’s 1999 short film The Wind Within (鹿港情深). All the films have English subtitles. To inquire about the set, call (02) 2396-5560 or e-mail hmc_films@yahoo.com.

Nov. 11 to Nov. 17 People may call Taipei a “living hell for pedestrians,” but back in the 1960s and 1970s, citizens were even discouraged from crossing major roads on foot. And there weren’t crosswalks or pedestrian signals at busy intersections. A 1978 editorial in the China Times (中國時報) reflected the government’s car-centric attitude: “Pedestrians too often risk their lives to compete with vehicles over road use instead of using an overpass. If they get hit by a car, who can they blame?” Taipei’s car traffic was growing exponentially during the 1960s, and along with it the frequency of accidents. The policy

Hourglass-shaped sex toys casually glide along a conveyor belt through an airy new store in Tokyo, the latest attempt by Japanese manufacturer Tenga to sell adult products without the shame that is often attached. At first glance it’s not even obvious that the sleek, colorful products on display are Japan’s favorite sex toys for men, but the store has drawn a stream of couples and tourists since opening this year. “Its openness surprised me,” said customer Masafumi Kawasaki, 45, “and made me a bit embarrassed that I’d had a ‘naughty’ image” of the company. I might have thought this was some kind

What first caught my eye when I entered the 921 Earthquake Museum was a yellow band running at an angle across the floor toward a pile of exposed soil. This marks the line where, in the early morning hours of Sept. 21, 1999, a massive magnitude 7.3 earthquake raised the earth over two meters along one side of the Chelungpu Fault (車籠埔斷層). The museum’s first gallery, named after this fault, takes visitors on a journey along its length, from the spot right in front of them, where the uplift is visible in the exposed soil, all the way to the farthest

The room glows vibrant pink, the floor flooded with hundreds of tiny pink marbles. As I approach the two chairs and a plush baroque sofa of matching fuchsia, what at first appears to be a scene of domestic bliss reveals itself to be anything but as gnarled metal nails and sharp spikes protrude from the cushions. An eerie cutout of a woman recoils into the armrest. This mixed-media installation captures generations of female anguish in Yun Suknam’s native South Korea, reflecting her observations and lived experience of the subjugated and serviceable housewife. The marbles are the mother’s sweat and tears,