Jamaica, where Kerry Young was born in 1955, is an island of bewildering mixed bloods and ethnicities. Lebanese, British, Asian, Jewish and aboriginal Taino Indian have all intermarried to form an indecipherable blend of Caribbean peoples. In some ways, this multi-shaded community of nations was a more “modern” society than postwar Britain, where Jamaicans migrated in numbers during the 1950s and 1960s. British calls for racial purity often puzzled these newcomers from the anglophone West Indies, as racial mixing was not new to them. Jamaica remains a nation both parochial and international in its collision of African, Asian and European cultures.

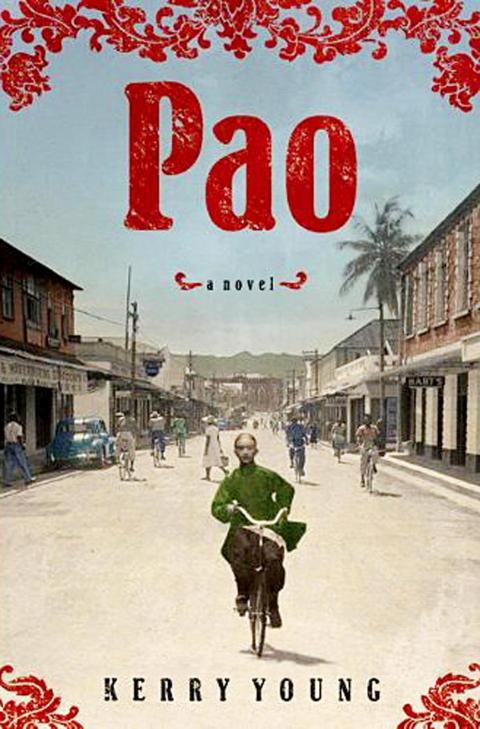

Young, the daughter of a Chinese father and a mother of mixed Chinese African heritage, came to Britain in 1965 at the age of 10. Pao, her zingy first novel, lovingly recreates the Jamaican-Chinese world of her childhood, with its betting parlors, laundries, fortune-telling shops, supermarkets and (business being a hard game in Jamaica) gang warfare. The Chinese first arrived in Jamaica in the 1840s, we learn, as indentured laborers. Having escaped this indignity, they set up business in the Jamaican capital of Kingston selling lychee ice cream, oysters and booby (sea bird) eggs. Racial tensions developed between them and their black neighbors; mixed marriages were generally frowned on. Ian Fleming, in his Jamaican extravaganza Dr No, wrote disapprovingly of the island’s yellow-black “Chigroes.”

Pao, the novel’s eponymous hero, arrives in Jamaica in 1938 a year after the Japanese invasion of China. Emperor Hirohito’s troops have bestially slaughtered some 150,000 Chinese in Nanjing. Terrified, Pao finds sanctuary with a Kingston elder and strongman named Zhang. Like many Jamaican Chinese, Zhang is a Buddhist convert to Catholicism. A razor-sharp tradesman, he owns all the “Chiney shops” and Catholic charities in the vicinity of Chinatown’s Barry Street. The teenage Pao aspires to be like Zhang, but incurs his displeasure one day by consorting in public with a black prostitute called Gloria Campbell. What Pao needs is a nice Chinese girl, Zhang insists, not a black whore.

In time, Pao marries the “socially acceptable” daughter of a Chinese merchant. However, Fay Wong disapproves of her husband as he continues to see Gloria on the sly. The couple fight endlessly. (“She even try to hit me with the bedside lamp but the electric cord stop her short.”) On Zhang’s death, Pao is appointed the most powerful man in Chinatown, with contacts in the Chinese freemason societies known as Tongs. Inevitably, the 21-year-old is involved in shady business, yet he retains a likeably high-spirited charm and humor. (Apparently he is based on the author’s father, Alfred Young, himself a former Chinatown bigwig.)

Along the way, Young provides a micro-history of Jamaica from its independence in 1962 to the present day. In 1965, dreadfully, Chinese properties were set ablaze in Kingston and the owners even “chopped” with machetes. “It was open warfare in the street,” writes Young, as it was believed the Chinese were in business solely to exploit black Jamaicans. Half a century on, the problem of the color line continues to haunt Jamaica. The lighter your complexion, the more privileged you’re likely to be. In pages of patois-inflected prose, Pao celebrates the island’s vibrant ethnic mix-up. Not all Jamaicans are black. Many gradations — Chinese, Indian, Lebanese — can exist within a single family. “They got every shade from blue-black to all sort of brown,” Pao comments, adding: “They even got some with ginger hair.” Eventually he abandons Fay and her wardrobe of silk cheongsams for the Africa-black Gloria.

Poignantly, Pao celebrates a vanished world. Jamaica’s Chinatown disappeared when Kingston railway station closed in the early 1990s. Few Chinese businesses operate there now; the old shops are boarded up or else serve as crack dens. Pao, meanwhile, confirms Young as a gifted new writer. Her novel is a blindingly good read in parts, both for its mesmeric storytelling and the quality of its prose.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) hatched a bold plan to charge forward and seize the initiative when he held a protest in front of the Taipei City Prosecutors’ Office. Though risky, because illegal, its success would help tackle at least six problems facing both himself and the KMT. What he did not see coming was Taipei Mayor Chiang Wan-an (將萬安) tripping him up out of the gate. In spite of Chu being the most consequential and successful KMT chairman since the early 2010s — arguably saving the party from financial ruin and restoring its electoral viability —

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,