Many people are already looking forward to the Lunar New Year holiday at the end of the month, but these days the event is generally a simple affair of the family getting together for a meal. Though there is no shortage of spring couplets and New Year delicacies, the elaborate symbolism that affirmed the natural order of nature and of political power that made the New Year such an important event in the Chinese calendar has gradually faded. As a little reminder, the National Palace Museum has set up a small exhibition entitled New Year Paintings of the Ch’ing (Qing) Capital (京華歲朝), which presents 12 works from the Qing Dynasty related in various ways to New Year celebrations.

The center piece of the exhibition, Synergy of the Sun, Moon and the Five Planets (日月合璧五星聯珠圖), was painted in 1761 in the 26th year of the Qianlong (乾隆) Emperor’s reign. It depicts the cosmic order as represented within the imperial city of Beijing from the purlieus to the center of power, the Forbidden City itself. The scroll, which is more than 13m in length, shows the activities of the city’s people, from peasant children playing on a frozen river to high court officials preparing to offer New Year salutations to the emperor.

According to curator Lina Lin (林莉娜), the painting’s creator was not only intimately acquainted with the city and the people he depicted, but was also a skilled cartographer. His representation of the city is accurate, Lin said, in depicting the capital as it was before the famous hutongs (衚衕), or narrow streets, were flattened. This is the first time this work has been put on public display in Taiwan.

Other exhibits also feature the same focus on detail, such as Joyous Celebration of the New Year (歲朝歡慶圖) by Yao Wen-han (姚文瀚), which depicts a well-to-do family celebrating the New Year. This is another painting that repays detailed study. It shows the whole household, from the master and mistress of the house at the dining table, to maids in the kitchen and the children at play. Also painted at the zenith of the Qing Dynasty, it is a scene of idealized celebration. Pictorially, it is interesting to note the rudimentary use of perspective and shading, devices imported by the Jesuits residing at the Chinese court, and ironically, harbingers of the dynasty’s eventual demise at the hands of Western arms.

Another highlight of this small show is Nine Goats Opening the New Year (緙繡九羊啟泰), a silk tapestry ornamented with embroidery. Lin said that the demands of time, money and skill meant that a work like this is extremely rare, even within the imperial collection. “It piles refinement on refinement,” Lin said, “as she pointed out the fine detail and the textured effects produced by the overlay of embroidery over the already detailed tapestry. This, as with other works on display, are all from a period of enormous prosperity and self-confidence, and this gives these celebratory works an exuberance that is manifest to the non-specialist, even if some of the finer detail is missed.

The main points of interest are highlighted and the esoteric language of auspicious symbols explained in an enormously helpful brochure in Chinese and English. Though the exhibition is small, it more than makes up for size in the enormous amount of detail that there is to appreciate.

In 2020, a labor attache from the Philippines in Taipei sent a letter to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs demanding that a Filipina worker accused of “cyber-libel” against then-president Rodrigo Duterte be deported. A press release from the Philippines office from the attache accused the woman of “using several social media accounts” to “discredit and malign the President and destabilize the government.” The attache also claimed that the woman had broken Taiwan’s laws. The government responded that she had broken no laws, and that all foreign workers were treated the same as Taiwan citizens and that “their rights are protected,

A white horse stark against a black beach. A family pushes a car through floodwaters in Chiayi County. People play on a beach in Pingtung County, as a nuclear power plant looms in the background. These are just some of the powerful images on display as part of Shen Chao-liang’s (沈昭良) Drifting (Overture) exhibition, currently on display at AKI Gallery in Taipei. For the first time in Shen’s decorated career, his photography seeks to speak to broader, multi-layered issues within the fabric of Taiwanese society. The photographs look towards history, national identity, ecological changes and more to create a collection of images

The recent decline in average room rates is undoubtedly bad news for Taiwan’s hoteliers and homestay operators, but this downturn shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. According to statistics published by the Tourism Administration (TA) on March 3, the average cost of a one-night stay in a hotel last year was NT$2,960, down 1.17 percent compared to 2023. (At more than three quarters of Taiwan’s hotels, the average room rate is even lower, because high-end properties charging NT$10,000-plus skew the data.) Homestay guests paid an average of NT$2,405, a 4.15-percent drop year on year. The countrywide hotel occupancy rate fell from

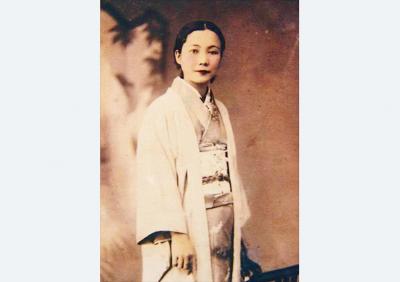

March 16 to March 22 In just a year, Liu Ching-hsiang (劉清香) went from Taiwanese opera performer to arguably Taiwan’s first pop superstar, pumping out hits that captivated the Japanese colony under the moniker Chun-chun (純純). Last week’s Taiwan in Time explored how the Hoklo (commonly known as Taiwanese) theme song for the Chinese silent movie The Peach Girl (桃花泣血記) unexpectedly became the first smash hit after the film’s Taipei premiere in March 1932, in part due to aggressive promotion on the streets. Seeing an opportunity, Columbia Records’ (affiliated with the US entity) Taiwan director Shojiro Kashino asked Liu, who had