Neither critical success nor the adoration of thousands of teenage girls has gone to the head of My Chemical Romance singer Gerard Way, or so it seemed when he entered the Far Eastern Hotel's Platinum Suite without personal assistants on Saturday evening, preceded by only his younger brother and the band's bass player, Mikey. My Chemical Romance - which played in front of 3,500 mostly college-age fans at National Taiwan University Athletic Stadium on Sunday - is nearing the end of a year-long tour to support The Black Parade, the platinum-selling, unabashedly over-the-top concept album about a dying cancer patient obsessed with redemption and revenge.

Sitting with his legs crossed, wearing dark Ray Bans that obscure his eyes, Way starts the interview by measuring the success of that album, which has been compared with Pink Floyd's epic The Wall. "To us Black Parade was the best record of that year," 2006. "That's how we felt about it when we were making it; we still feel that way about it. But something like The Wall is hugely ambitious. I don't know what it takes to make a record like that. I think you gotta take a sledgehammer to your life in a lot of ways and I don't think anyone in this band is prepared to do that."

Ron Brownlow: On this tour until really recently you would come out and say you were the Black Parade, at least for the first hour. And then you stopped last month.

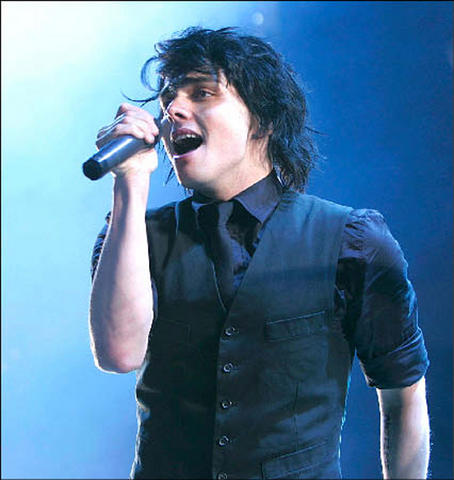

PHOTO: AP

Gerard Way: We were filming a show in Mexico, and maybe 10 minutes before we went on we just decided that it was going to be the last one. We felt like we'd done all we could as the Black Parade and we really wanted to go back to simply being My Chemical Romance. And that's just really being a great rock band.

RB: So part of it was you were on the road for so long you were just sick of doing it?

GW: Actually a small part of it was that. It caged us. But a bigger part was, I think, everything attached with being the Black Parade was something we wanted to kind of move on from.

(Way identified so much with the character in the album, known only as the Patient, that until recently he assumed the persona on stage. He cropped his black hair short and dyed it silvery blond to, he says, "appear white and deathlike." Members of My Chemical Romance wore matching black uniforms, and the band played part of each concert under the pseudonym The Black Parade.)

RB: So can we still talk about the Patient?

GW: Yeah! Of course.

RB: How is the Patient right now?

GW: (Laughing.) I always like to feel that that particular character was created so everyone could identify with the character. Most likely everyone is eventually going to become a patient, and that's going to be the last time you are a patient. You kind of lose your sense of identity; and if you don't have any family around you, you even have less of an identity. But I like to think that, at the end of that record, the character gets a second chance, which you rarely get, you know? I'd like to think whether or not the character dies, he does in fact choose to live.

RB: I was reading a New York Times story that said the Patient is the American Everyman recast as a sick, violence-scarred wreck.

GW: I'd say that's pretty close. It's definitely an Everyman. I don't think largely American, though. We had sought out to make a universal record, and just the fact that we're here today proves that we did. It's interesting. We don't really think of ourselves as a New Jersey band. And we also don't think of ourselves as an American band in a lot of ways. We felt more a band of the world or somewhere like the UK. We felt more like a British rock band than anything.

(Born on April 9, 1977, Gerard Way grew up in blue-collar Belleville, New Jersey, roughly 15km from Manhattan. When he was a teenager, he was held up at gunpoint. According to an article in Rolling Stone magazine, Way said a .357 Magnum was pointed to his head, and he was "put on the floor, execution-style." He graduated from the School of Visual Arts in New York City and was working in the comic book industry there when, on Sept. 11, 2001, terrorists crashed two airliners into the World Trade Center. Twice when we're talking about Sept. 11, his voice tails off.)

RB: Did you see the planes crash into the World Trade Center?

GW: I was taking the commuter train in. I didn't see any of the planes hit. I did see the buildings go down, from I'd say fairly close. It was like being in a science fiction film or some kind of disaster film - it was exactly that kind of feeling. You didn't believe it. You felt like you were in Independence Day. It made no sense. Your brain couldn't process it. And for me it was a little different. I'm very empathetic and I'm kind of a conduit emotionally, so I pick up a lot of stuff in that way. There was about three- or four-hundred people around me - and I was right at the edge. All these people behind me, they all had friends and family in those buildings. I didn't. So when that first building went, it was like an A-bomb went off. It was like just this emotion and it made you nauseous. One of the first thoughts that went through my head when they went down was, "What does this mean?"

RB: How did that lead to the creation of the band?

GW: One of the other things I thought about when the first building went down was, "Everything's kind of pointless that you're doing right now." I was involved in commercial art in New York, trying to pitch a show to the Cartoon Network that was extremely frustrating because I was dealing with a company that had optioned the cartoon show that didn't quite get it. I think they were more interested in turning it into toys and pillowcases and shit like that, and it was really disheartening. That was my first ever taste of creating something and seeing it take off a little bit - and it didn't feel good. At that moment I was like, "This doesn't mean anything. This is all garbage. This is all bullshit. I need to do something that actually means something, or my life's gonna mean nothing. Just like this cartoon means nothing."

RB: Do you think you've found meaning through this?

GW: I think we created something special together. I think it means something. It meant something when it started, it said what it kind of had to say, and so that's an interesting position to be in because I don't necessarily think that the next album we make, I don't necessarily think that it needs to mean something. I think we're kind of finished in that regard. So it's gonna be interesting to see what we do next because, quote unquote "the mission" or "the goal," I feel very complete about that.

(Way and My Chemical Romance are polarizing figures. In a Kerrang! magazine poll, the band was voted both best and worst band of 2006. Appearing with the band at that year's Reading Festival in England, Way, known for his onstage histrionics, was pelted with a bottle of urine and other objects thrown from the audience. That same year, Welcome to the Black Parade reached number one on the UK Singles Chart, as it did in the US. The album has gone platinum in both countries.)

RB: Getting bottled. What did that feel like?

GW: It was exhilarating and extremely challenging. There's nothing like that to humble you more and let you know that there's still something to fight for.

RB: You felt exhilarated?

GW: Yeah! I think when all is said and done people will look at that very specific show and say that was the most important show of this band's career, because they got up there facing a tremendous amount of opposition and won an entire crowd over and did it with the camera on them and everybody facing them. I think that's why it's important because it really sums up the band in one 40-minute set. It was not easy. It was a volley at first and then just it stopped and there was cheering and there was excitement and there was positivity. A current through the audience. It's amazing to watch footage BBC captured.

RB: You've said the band started as your therapy, and then it became the band's therapy, and then we became other people's therapy.

GW: It was kind of a therapy for me at first because of 9/11, and then the band because, in some way, we, in our own lives, had been the people that did not fit in or weren't built like other people - just not prone to violence. Not survivors in that regard. Survivors in a different way. And so then when we'd go to these shows we started meeting these kids just like us. And so that was almost like a group therapy session. That was really exciting. We're just all working it out. Since we're very non-violent people in our everyday lives and our fans are very much the same. They're very much like shy, quiet loners. You have to have some place you need to kind of get that out. Our shows were the place to do it. One of the things that's a common misconception about the punk rock scene is that what's cool about it is you could go and fit in because it's punk rock. But in actuality you can't. I don't think enough people say this about it. It was the same as being in high school with jocks. I would go to punk clubs and get shoved by skinheads because I wasn't like them, which was just like getting shoved by jocks wearing a Ramones shirt.

RB: You've talked about failure. You said, "I have failed a great deal in my life with everything I've tried to do. I was a failed artist. I was a failed animator-this-that-and they other thing … I was always very close but I was always not quite there."

GW: Maybe it's not so much failure so much as it is not following through and giving up. I think I was more of a person that gave up, rather than a failure. I didn't have what it took at the time, because I was very prone to get discouraged very quickly and stop doing what I was doing. With this band I was never one to give up.

(Although My Chemical Romance cites as influences everything from Queen, Thursday and Iron Maiden and to Morrissey, Black Flag and the Smashing Pumpkins, it is often referred to as an emo band, a label the band vigorously protests. Originally used as shorthand for the "emotional hardcore" subgenre of punk that originated with Washington, DC, it now refers to a vaguely defined genre of punky, goth-leaning indie-rock whose adolescent followers are stereotypically shy, angst-ridden and prone to depression and self-injury. Way has called emo "a pile of shit," but My Chemical Romance's dramatic style connects with a very teenage intensity of emotion. In interviews, Way and other band members have openly discussed their mental-health issues, and their penchant for tight jeans and eyeliner makes them look very much the part.)

RB: You really hate being called an "emo" band. Why do you despise that term so much?

GW: I don't like any term that to me seems lazy or an easy term for something that's not easy to describe. I also think it's frustrating. We were so the opposite of the emo band that we couldn't get booked playing shows, because there was this budding emo scene, and we literally were touring with Christian-metal bands, or other bands that were very off-kilter as well. We were almost created in opposition to that. We were like the answer to what was happening.

We didn't fit in with this dungareed, moppy-haired, whining-about-girl type of nonsense. I just wish people would realize that what happens with My Chemical Romance is completely exclusive from any other kind of genre of music. What we have is extremely special. And we've worked very hard to get it there. So it's an insulting term in the fact that we're lumped in with bands that didn't create that. They didn't put in the work and they didn't slug it out to create something that was unique for us and our fans. It's just for us and the fans, it's not for anybody else. If the fan base is huge, that's awesome. If it's small, same thing.

The whole phenomena of the band has nothing to do with what people are calling emo. It's not at all like that. It wasn't founded on the same things. The blood that went into it was different. [Emo] didn't have the spit, it doesn't have the grit of it. It's not unique. It's just pop-punk all over again. Now it's pop-punk with eyeliner. All of it's boring and really redundant. That's why it's frustrating, because it was difficult for us starting out because we were nothing like that.

RB: What do you see on the horizon after this tour?

GW: I see our first kind of lengthy break. We're gonna commit to trying to have at least six months off before we even talk about making something else. And then at that point, hopefully, we will have done enough living to make something.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

April 14 to April 20 In March 1947, Sising Katadrepan urged the government to drop the “high mountain people” (高山族) designation for Indigenous Taiwanese and refer to them as “Taiwan people” (台灣族). He considered the term derogatory, arguing that it made them sound like animals. The Taiwan Provincial Government agreed to stop using the term, stating that Indigenous Taiwanese suffered all sorts of discrimination and oppression under the Japanese and were forced to live in the mountains as outsiders to society. Now, under the new regime, they would be seen as equals, thus they should be henceforth

Last week, the the National Immigration Agency (NIA) told the legislature that more than 10,000 naturalized Taiwanese citizens from the People’s Republic of China (PRC) risked having their citizenship revoked if they failed to provide proof that they had renounced their Chinese household registration within the next three months. Renunciation is required under the Act Governing Relations Between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area (臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例), as amended in 2004, though it was only a legal requirement after 2000. Prior to that, it had been only an administrative requirement since the Nationality Act (國籍法) was established in

With over 80 works on display, this is Louise Bourgeois’ first solo show in Taiwan. Visitors are invited to traverse her world of love and hate, vengeance and acceptance, trauma and reconciliation. Dominating the entrance, the nine-foot-tall Crouching Spider (2003) greets visitors. The creature looms behind the glass facade, symbolic protector and gatekeeper to the intimate journey ahead. Bourgeois, best known for her giant spider sculptures, is one of the most influential artist of the twentieth century. Blending vulnerability and defiance through themes of sexuality, trauma and identity, her work reshaped the landscape of contemporary art with fearless honesty. “People are influenced by

The remains of this Japanese-era trail designed to protect the camphor industry make for a scenic day-hike, a fascinating overnight hike or a challenging multi-day adventure Maolin District (茂林) in Kaohsiung is well known for beautiful roadside scenery, waterfalls, the annual butterfly migration and indigenous culture. A lesser known but worthwhile destination here lies along the very top of the valley: the Liugui Security Path (六龜警備道). This relic of the Japanese era once isolated the Maolin valley from the outside world but now serves to draw tourists in. The path originally ran for about 50km, but not all of this trail is still easily walkable. The nicest section for a simple day hike is the heavily trafficked southern section above Maolin and Wanshan (萬山) villages. Remains of