It seems curious, given the circumstances, that Krystian Bala should feel the need to be polite. When a man is serving 25 years for murder, you do not expect him to apologize for smoking a cigarette.

"Do you mind?" he asks, fishing out a pristine packet of Red & White from his shirt pocket. "I gave up a year and four months ago but then I started again since all of this."

He gestures vaguely with his hand, taking in his surroundings with a brief, unconcerned glance: the grubby prison visiting room, the gray-suited warders, the small metal cage he must be locked inside before being allowed to speak to anyone from the outside world.

PHOTO: AP

"It is ridiculous what's going on here," he says, shaking his head. "That I should be in jail just because someone drew the wrong conclusion from an innocent work of fiction."

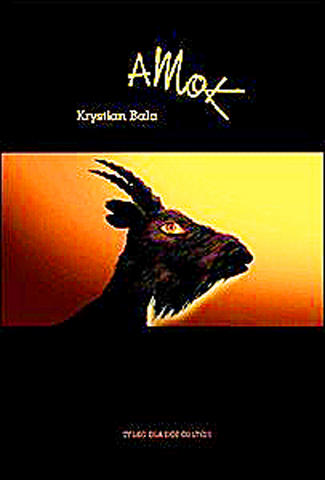

Balanced on the narrow ledge in front of him is a slim, black book, its pages carefully annotated in blue Biro, corners folded over to mark relevant passages. Its Polish title is typed on the cover in yellow print: Amok, by Krystian Bala.

As he talks, Bala bends back its spine and thumbs through the volume urgently, his eyes, framed by square wireless spectacles, skimming rapidly across the page. When he finds the phrase he is searching for, he slides it through a letterbox-sized slot cut into the metal bars.

PHOTO: AP

"I can defend every single sentence," he says, jabbing at the typed pages with stubby fingers.

As he gets more animated, his stilted conversational English breaks into the hiss and spit of quickfire Polish. This is the first time Bala has agreed to speak to a journalist since his incarceration - and he has plenty to say. "Of course, the book is brutal, vulgar, the dirtiest I could write, but that's how art must be provocative. Just because I write a murder, doesn't mean I did it in real life."

The Polish courts drew a different conclusion. On Sept. 5 in a court in the Lower Silesian city of Wroclaw, Bala, 34, was found guilty of co-coordinating the torture, semi-starvation and eventual murder of his ex-wife's former lover. It was the most sensational trial in recent Polish history, its every detail pored over by the local press and recounted breathlessly to a stunned public. One of the main pieces of circumstantial evidence against Bala was his own book, in which an eerily similar murder was committed by the protagonist. According to the prosecution, Bala's narrative contained a level of detail about the actual killing of Darius Janiszewski that only the investigating police officers or the murderer could possibly have known.

It was a peculiarly specific crime. The bloated, semi-naked body of Janiszewski, a 35-year-old advertising company director, was discovered by anglers on the banks of Wroclaw's River Odra on a washed-out, gray December morning in 2000. He had been missing for more than a month. The corpse bore livid bruises from repeated beatings and a series of knife wounds. Over the subsequent days, the police pathologist would find that Janiszewski had been denied food and water for three days before his death.

The first police officers on the scene were struck by the strange way the victim had been tied up: his feet had been bound together, bent backwards and attached to a noose around his neck with a single piece of rope. Trussed up like a human cat's cradle, Dariusz Janiszewski would have strangled himself had he flexed his legs too suddenly. No one knows whether he suffocated in this way before being thrown in the Odra or whether he drowned there.

It was a brutal death, but it would have an even more gruesome coda. The first police investigation was abandoned in May 2001 after officers failed to find a single lead. Then, a year later, during a routine police review of unsolved cases, it was noticed that Janiszewski's mobile phone had never been recovered from the murder scene.

The service provider traced his SIM card and, astonishingly, discovered that it was being used by an unsuspecting businessman who had bought the mobile from an Internet auction site on Nov. 16, 2000 - three days after Janiszewski's disappearance and several weeks before his body was found.

The phone had been sold for about US$88 on the Allegro Web site by someone with the Internet username ChrisB7. A cursory police search revealed that ChrisB7's account was registered to a Krystian Bala. That, in turn, led them to his blog, a series of demented personal ramblings that would, three years later, be published as Amok.

Amok did not sell particularly well when first published by Bala's friend, despite the enticing cover catch-line that it was intended "for adults only." The few who read it were treated to a pulp-fiction orgy of bestiality, pornographic oedipal complexes and indiscriminate sexual violence. But they might also have noted - as police officer Jacek Wroblewski did - the vivid description of the murder of a young woman called Mary, tied up in almost exactly the same way as Janiszewski, stabbed with a Japanese-made knife and left to die. The narrator - referred to throughout as Chris B - even sells the bloodied murder weapon on the internet auction site Allegro.

EVIDENCE MOUNTS

It made unpleasant reading for Wroblewski, a mild-mannered and jovial 42-year-old with close-cropped brown hair and a generous paunch that spills over his waistband. When he smiles, his whole face reddens. "For me, it's not a book," he says, sitting in a small side-office at Wroclaw police headquarters, fishing out a Lipton teabag from a cup and placing it carefully on the saucer. "It's hardcore pornography. It's very vulgar and it was hard for me to read it, but I knew I had to. There were specific elements which matched exactly the way the murder was carried out. And, more than that, there are pieces which show that Krystian Bala wrote this book as a kind of private diary."

There were other slivers of evidence, too. Further to a 2003 TV appeal for information about the crime, the producers of the show reported getting hits on their Web site from computers in Singapore, South Korea and Japan. The police discovered that Bala was visiting those countries on a scuba-diving trip on the relevant dates.

Bala was arrested one mild evening in September 2005 as he walked to the chemist in shorts and T-shirt in his parents' hometown of Chojnow, southern Poland. Although he denied ever meeting the murder victim, a search of his bedroom revealed a stash of computer files containing information on Janiszewski and a pen bearing the logo of Janiszewski's advertising firm, Investor. A telephone card recovered in the search was later shown to have been used on the day of Janiszewski's disappearance to make calls to the victim's mother and his place of work. The same card had registered calls to Bala's family and friends.

Further investigations revealed that Bala's ex-wife, Stanislawa, from whom he separated in 1999 and with whom he has a 10-year-old son, Kaspar, had been dating Janiszewski for a short period in the summer of 2000.

Bala, a highly intelligent philosophy graduate with a seemingly unblemished past, now found himself accused of killing his ex-wife's boyfriend in a fit of jealous rage. "Am I certain he is guilty?" says Wroblewski. "I am 100 percent sure."

Indeed, Bala himself spontaneously confessed to the murder in April 2006, but then refused to sign the statement, claiming he had been "unwell" at the time.

But there remains a substantial element of doubt concerning Bala's conviction. The evidence against him, however damning, was also entirely circumstantial. "I don't deny that Krystian Bala had the victim's mobile phone in his possession but the prosecution failed to establish how he got it," says Bala's lawyer, Karol Weglinski. "Having an object in one's possession is not the same as having killed the owner. A murder must be judged on evidence that is beyond reasonable doubt."

The judge, Lidia Hojenska, further admitted that it was unlikely Bala had acted alone - Janiszewski was 190cm and broadly built. Bala is barely 168cm and looks more like a postgraduate student than a criminal mastermind.

Bala has already been languishing in custody here for 20 months, kept in an 18m2 cell with up to seven other men, with one hour's outside exercise a day.

"I've been spending my time getting gray hairs," he says. "When I was a free man I didn't know one minute of boredom. Now I've lost my life."

He will remain in custody for the next two to three weeks while awaiting the outcome of his leave to appeal. This means that Bala continues to have freer access to books, clothes and family visits than regular inmates in the main prison.

Talking to him is an exercise in frustration. He refuses to address the evidence stacked up against him, dismissing the case as a giant police conspiracy to dismantle his right to freedom of expression. He claims he found Janiszewski's mobile in a cafe and brushes aside inconvenient facts as lies. Through the course of our hour-long conversation, he compares himself variously to Ludwig Wittgenstein, Daniel Defoe, Philip Roth, Salman Rushdie, Henry Miller and William Burroughs. He likes to make facile puns - "They call it the system; I call it the shitstem" - delivering them with a half-smile, then repeating them to ensure the joke has registered.

In court, much was made of Bala's apparent superiority complex. Two independent psychologists found he had a high IQ and was mentally accountable for his actions but diagnosed a narcissistic emotional disorder that left him incapable of empathy, with an extreme hatred of criticism.

Several character witnesses came forward to testify that Bala was an aggressive drunk and a borderline compulsive liar, prone to frequent outbursts of "pathological jealousy." His three-year marriage to Stanislawa was punctuated by physical violence, to the extent that the Polish police placed the family on a domestic violence register called the "Blue Card" scheme.

When the couple eventually separated in 1999, Bala became obsessed with tracking his wife's new partners, sending her abusive e-mails and text messages. At a New Year's Eve party the same year, Bala verbally threatened a barman he thought had been flirting with Stansilawa. Two witnesses heard Bala warn him off with the words: "I've already taken out a guy like you with a rope."

What made Bala the man he became? He was born into a stable and loving family in the Upper Silesian city of Katowica, the elder of two children - his younger brother, Adrian, 26, is a computer programmer. When Bala was 15, the family moved to be closer to his extended family in his mother's hometown of Chojnow, a small rural hamlet 100km outside Wroclaw.

His boyhood home is a picturesque country villa, built by his construction worker father, Stanislaw, and reached by a short driveway that cuts through a garden filled with white wild flowers and peach trees.

"Krystian loved the plants and the wildlife," remembers his mother, Teresa. "His father used to take him angling, and whenever he caught a fish he wouldn't want to kill it. He would say, "You can have it if you want, but I want to set it free."

Inside, the walls of the large, draughty rooms are crammed with family photographs. The sofa is piled high with an assortment of Krystian's certificates - a scuba-diving qualification, a masters diploma, a glowing reference from a university professor.

"I just want to show you something good about my son," says Teresa, a homely woman with a cheery smile and florid cheeks. "Please understand me."

"I am completely sure that my son is innocent," says Teresa, 53, a sales director at a farm equipment company. "He was so sensitive as a child, so good. He loved animals. He had turtles, parrots, fish. He was able to read when he was five. He talked easily to people and made friends.

"What we heard in court about him was so far-fetched," adds Stanislaw, 61, sitting impassively to one side, staring out of the window. "I just couldn't understand it."

It is clear that the Balas are by turns baffled and distraught by what has happened. They were so convinced that the court would release their son at the end of his trial that they had already prepared a "Welcome Home" banner.

'ANSWERLESS QUESTIONS'

Academically-minded from a young age, Bala excelled at the local secondary school and was the first in the family to go to university, studying philosophy as an undergraduate at the University of Wroclaw and then staying on to do a masters.

He was good-looking and popular with the girls - his friends nicknamed him Amora, the Polish equivalent of Casanova. But there was no serious girlfriend until he met Stanislawa in 1993, on one of his regular fishing trips. They got married in 1996. Krystian was 23. The wedding photographs show him with long curly hair down to his shoulders, looking like the quintessential student.

When Krystian moved out of the couple's Wroclaw apartment in 1999, he hired a private detective to monitor his wife's movements. The discovery, shortly afterwards, that she was seeing Dariusz Janiszewski, a good-looking young advertising executive with an easy-going nature and a taste for Led Zeppelin, set in motion a disastrous chain of events. It would culminate in Janiszewski's brutal death and the bizarre retelling of his gruesome murder, three years later, in a thinly veiled work of fiction.

Krystian Bala's own narrative has yet to reach its conclusion. He is preparing an appeal with his lawyer and plans to sue the police for damages. He is even working on his second novel, which he promises with some relish will be "even more scandalous" than the first. Does he feel any compassion for Janiszewski's family?

"It's a tragedy for them," he says. "But I hope they want to find the truth. The people who did this have still not been found. There are answerless questions still."

As he is unlocked from his metal cage by a prison warder and led back down the corridor, the soles of his sandals squeaking against the linoleum floor, he stops suddenly and turns round. "Thumbs up!" he shouts after me. I look back to see him grinning, one of his arms outstretched, his thumb pricked up like an over-excited tourist on a day-trip to Disneyland.

It is a gesture so utterly misplaced, so strangely callous, that for all the disturbing police reports, the tales of remorseless violence and senseless death, it is this memory that will lodge in my mind for days afterwards: the sight of Krystian Bala, convicted murderer, doing the thumbs-up sign, a shard of light glinting off his spectacles and half-obscuring his smiling eyes.

When the South Vietnamese capital of Saigon fell to the North Vietnamese forces 50 years ago this week, it prompted a mass exodus of some 2 million people — hundreds of thousands fleeing perilously on small boats across open water to escape the communist regime. Many ultimately settled in Southern California’s Orange County in an area now known as “Little Saigon,” not far from Marine Corps Base Camp Pendleton, where the first refugees were airlifted upon reaching the US. The diaspora now also has significant populations in Virginia, Texas and Washington state, as well as in countries including France and Australia.

On April 17, Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) Chairman Eric Chu (朱立倫) launched a bold campaign to revive and revitalize the KMT base by calling for an impromptu rally at the Taipei prosecutor’s offices to protest recent arrests of KMT recall campaigners over allegations of forgery and fraud involving signatures of dead voters. The protest had no time to apply for permits and was illegal, but that played into the sense of opposition grievance at alleged weaponization of the judiciary by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) to “annihilate” the opposition parties. Blamed for faltering recall campaigns and faced with a KMT chair

As we live longer, our risk of cognitive impairment is increasing. How can we delay the onset of symptoms? Do we have to give up every indulgence or can small changes make a difference? We asked neurologists for tips on how to keep our brains healthy for life. TAKE CARE OF YOUR HEALTH “All of the sensible things that apply to bodily health apply to brain health,” says Suzanne O’Sullivan, a consultant in neurology at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery in London, and the author of The Age of Diagnosis. “When you’re 20, you can get away with absolute

A police station in the historic sailors’ quarter of the Belgian port of Antwerp is surrounded by sex workers’ neon-lit red-light windows. The station in the Villa Tinto complex is a symbol of the push to make sex work safer in Belgium, which boasts some of Europe’s most liberal laws — although there are still widespread abuses and exploitation. Since December, Belgium’s sex workers can access legal protections and labor rights, such as paid leave, like any other profession. They welcome the changes. “I’m not a victim, I chose to work here and I like what I’m doing,” said Kiana, 32, as she