Against all expectations, the elephant was not in the room. Come Friday evening, at the end of its first full day as an art object, the elephant had probably gone for a lie down, drained by all the attention it had received.

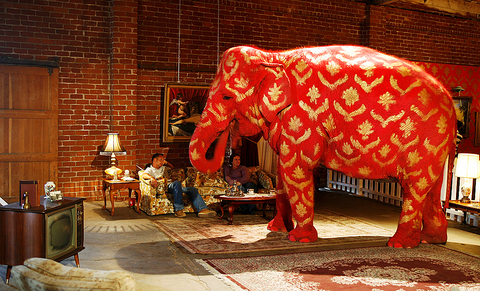

The previous night, at the glamorous opening in the decidedly un-Beverly Hills setting of a disused warehouse at the end of a cul de sac nestled close to a downtown freeway interchange, the elephant had upstaged some of Hollywood’s finest. Painted red, adorned with gold fleur-de-lis, the elephant merged into the wallpaper behind it. There was nothing that Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie could do other than gawp.

The stars, who also included Jude Law and Keanu Reeves, had gathered for the first LA show by the British prankster, provocateur, graffiti artist and general meddler, Banksy. Known for his street art and interventions in Britain, his show in LA, Barely Legal, was his first large-scale exhibition in the US. Complete with valet parking and a retinue of publicists, it is by far the most high profile of Banksy’s foreign jaunts, which have also taken him to Paris, New York and Israel.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

The show includes pieces of British iconography, such as a Guardsman on Horse Guards Parade atop a pantomime horse, in addition to work aimed specifically at the local audience. A police van dominates the entrance to the exhibition, decorated with a picture of Dorothy from The Wizard of Oz carrying a noose. Occupying an entire wall next to it is a painting reinterpreting an American icon, the raising of the flag at Iwo Jima. In Banksy’s interpretation, the scene is given an urban setting with a group of protesters raising the flag on top of a car.

The world of Brad, Angelina, Jude and Keanu is a long way from Banksy’s origins as a 14-year-old schoolboy in Bristol, England, dabbling in graffiti when it was considered an aggressive form of counterculture. The images that followed, daubed illegally on London’s walls, paved the way for the trend of appropriating public space by graffiti artists. His chutzpah rose to a higher plane earlier this year when he sprayed nine paintings on the 684km barrier that separates Israel from Palestinian territories. A stencil on a Bristol building was allowed to remain in place by the city council after the public voiced overwhelming support.

Yet somehow, despite his mainstream appeal, Banksy has lost none of the respect of his more “underground” British peers. “People have been doing graffiti [in the UK] for about 30 years, and it’s time it was taken seriously,” said “Tizer,” a south London graffiti artist who works on public murals and on education projects with young offenders. “When people talk about graffiti they talk about Banksy. Famous people have always come to his exhibitions because his stuff is easy to read.” A week before the Los Angeles exhibition, Banksy visited Disneyland, somehow managing to place an inflatable figure dressed as a Guantanamo detainee alongside a railroad ride. A short film of the escapade runs inside the LA show. In the same darkened screening room a glass case displays another of his recent interventions: the Paris Hilton CD doctored by Banksy, which he carried out with the help of Los Angeles-based producer Danger Mouse. Enormous cockroaches had been placed inside the display case. Like much of Banksy’s work, it is an overt statement. But of what, precisely?

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

“There’s more than one thing going on in every picture,” said Tarik, a chef who had seen Banksy’s work in a magazine and decided he had to see it for himself. “There’s a lot of tension in the pictures.”

Tarik gestures at a large painting showing a group of cavemen carrying spears approaching some shopping trolleys. “European artists are a lot more bold and willing to fight,” he says. “The concept of opposing your government is full of bullshit here.”

Banksy himself had displayed a fine sense of bullshit in an interview he gave to Roger Gastman published in the LA Weekly. “Some of the paintings have taken literally days to make,” he confided. “Essentially, it’s about what a horrible place the world is, how unjust and cruel and pointless life is, and ways to avoid thinking about all that. One of the best ways turned out to be sitting in a warehouse making paintings about cruelty, pain and pointlessness.”

Gastman, who edits a magazine called Swindle that features a longer interview with Banksy, thinks that the humor will not be lost on the LA audience. “His work is fun and witty when you see it in the street,” he said. “No matter what serious questions I asked his answers are very reflective of the humor in his work.”

In keeping with his secretive persona — there are no pictures of Banksy and his identity remains in doubt — the artist himself was probably not present at the opening. But that didn’t stop people asking. “Is the artist here,” asked J Mitchell, a singer. “Are you the artist?”

Josh, a computer programmer and stencil artist was impressed by the scale of the work. “He doesn’t do discreet like other stencil artists,” he said. “These are supposed to be here, in a gallery. He does it big, which is what graffiti artists have been doing for a long time.”

But in a town that takes its animal welfare very seriously, some took exception to the presence of the elephant. On entering, visitors were presented with a flyer reading: “There’s an elephant in the room. There’s a problem we never talk about. The fact is that life isn’t getting any fairer. 1.7 billion people have no access to clean drinking water... . Every day hundreds of people are made to physically be sick by morons at art shows telling them how bad the world is but never actually doing something about it. Anybody want a free glass of wine?”

Some of the money from the show will have come from the numbered prints on sale for US$500 each on the glitzy opening night. The rest will have come from the current market for his work, with Banksy’s pictures selling for upwards of US$75,000, according to his London agent Steve Lazarides.

Tai, the 38-year-old painted pachyderm was scrubbed down on Sunday on the orders of the Los Angeles department of animal services.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she