The blob of traffic in front of our car had stopped dead. Having arrived in Mandalay from crowded Bangkok, I'd hoped to escape gridlock, but here I was, just 30 minutes after touchdown at the airport, in bumper-to-bumper traffic again. Frustrated, I poked my head from the car, and was immediately pelted -- with garlands of jasmine.

I swiveled my head, and found myself staring into a crowd of Burmese girls standing on the bed of a truck festooned with ocher prayer flags. I had blundered into a novice ceremony, a festival celebrating the entrance of young girls into the local Buddhist nunnery. Burmese pre-teenagers in fuchsia and white robes, with crowns of garlands and gold leaf atop freshly shaven heads, stood on pedestals in the trucks, queens for the day. Truckloads of relatives held parasols over the girls' heads and tossed garlands into the street. Monks chanted while bands of wood drums and thin flutes belted out reedy atonal melodies.

As Southeast Asia modernizes rapidly, Myanmar remains the last country in the region preserved in amber. In Myanmar, men still wear sarong-like lungis rather than pants, and traditional rituals like the novice ceremony, rather than new-model Mercedes, still hold up traffic. Western influences are almost nowhere to be found. "We go nowhere," one Burmese business-man told me over drinks at a sailing club in the capital, where the wooden dinghies were cracking. "What can we do? Have another drink."

PHOTOS: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

There's a reason for this sensation of being stuck in time, of course. Decades of rule by one of the world's harshest military regimes have left the country isolated and its economy a shambles, discouraging tourist arrivals, putting modern amenities out of many people's reach, and keeping the Burmese wedded to traditional life. (Last year, Myanmar received some 660,000 foreign visitors, according to the government, compared with the more than 11 million in Thailand in 2004, as reported by the Tourism Authority of Thailand.)

"There's only one destination where we won't market holidays, and that's Burma," said Justin Francis of Responsible Travel, a British travel agent promoting socially responsible trips. "We'll market trips anywhere else where we think it'll benefit local people -- even Zimbabwe."

The country's name alone suggests the perplexing state of affairs, and the political side that some travelers take even before deciding whether to visit. What was once Burma was renamed Myanmar by a 1989 military edict. But some people in the West -- particularly those human rights activists who argue that the current regime is one of the most oppressive in the world and has used forced labor to build some tourist sites -- still call it by its traditional name.

PHOTO: NY TIMES NEWS SERVICE

Like Responsible Travel, and Aung San Suu Kyi, the pro-democracy opposition leader, many Myanmar-oriented human rights groups support a boycott of tourism, which they see as endorsing the government. The groups draw up "dirty" lists of travel agencies that send tourists there, blast publishers of Myanmar guidebooks, and try to shame celebrities who visit, like Mick Jagger. "It's naive to say you can help as a tourist," said Tricia Barnett, director of Tourism Concern, a British group advocating responsible tourism, who believes that most of the tourist infrastructure remains closely linked to the regime.

For other travelers, convinced their tourism dollars will help average Burmese, the appeal of the last truly Asian place in Southeast Asia is exactly the reason to come. "When I was in Burma, I've never met anyone who said that I shouldn't be there," said Andrew Gray, founder of Voices for Burma, another advocacy group. Gray argues that educated tourists can spend money on local businesses without government links and help average people in one of Asia's poorest nations.

I've visited Yangon, as Rangoon is now called, more than five times in the last decade, including most recently in March. Each time, I rise early my first morning for a pilgrimage to the northern end of the city's axis, the Shwedagon Pagoda. "It is of a wonderful bignesse, and all gilded from the foot to the toppe," wrote the first Englishman to visit Myanmar, Ralph Fitch, in 1586, upon glimpsing Shwedagon.

The pagoda still towers over the skyline today, a 99.4m-tall bell-shaped spire over 1,500 years old, gilded in layer after layer of precious metals and set with over 5,000 diamonds and other gems. Below the main spire sit hundreds of smaller stupas, and in the morning, Shwedagon's jewels reflect the sun like a disco ball, tossing multicolored light in every direction.

South of Shwedagon, in the middle of a busy intersection, lies the other end of the axis, the Sule Paya -- another gilded temple that's nearly 2,000 years old. Just outside Sule Paya, surrounded by traffic, I stop at a tea shop. Despite military rule, the Burmese remain avid consumers of news -- I see numerous people holding transistor radios to their ears -- and dispensers of gossip. And tea shops, where you can sit for hours digesting salads and Indian-style snacks and chewing betel nut, a mild narcotic whose red juices stain Yangon's streets, have always been where the best gossip is tossed around.

In the late 1980s, political conversations and fights at tea shops helped ignite an antigovernment revolt, which culminated in the party of Aung San Suu Kyi sweeping the national election in 1990, the first free vote in three decades. But the regime ignored Aung San Suu Kyi's victory and she has been under house arrest on and off since, along with at least hundreds of other political prisoners. In the last two years, the junta has become even more reclusive, moving ministry buildings from Yangon to a jungle redoubt in central Myanmar, reportedly on the advice of an astrologer. According to the Free Burma Rangers, a relief and advocacy organization based in Thailand, more than 11,000 Burmese have fled their homes in recent months.

Meandering south, I lose myself in the warren of crumbling colonial buildings, some with posters advertising screenings of Missing in Action, a 20-year-old Chuck Norris flick, or magazines 15 years out of date. Once scrubbed outposts of the British Raj, the buildings have begun to succumb to the humidity, but structures like the old High Court, an imposing Victorian red brick edifice crowned with a Big Ben-style clock tower, retain an imperial majesty. On the waterfront, I wander into the lobby of the Strand, the classic Yangon hotel where steamer ships once disgorged maharajahs, princes and other nobility of the Raj. Elegantly restored, down to the white-suited liverymen opening the hotel doors, from inside the Strand's tearoom one could still think the sun hasn't set on Britannia.

No pukka sahibs are in sight anymore outside the Strand, though -- Yangon, a city of some 4 million people, has become one of the most diverse cities in the region, and Myanmar has over 130 ethnic groups.

As I push through crowded alleys that smell like chapatis, I see ethnic Indians with henna-tinged beards and red dots on their foreheads eating masala dosa at street stalls and ethnic Chinese merchants weighing bars of gold on aging scales. At a biryani stall, I am surrounded by ethnic Burmans, the majority, smearing on thanaka, a paste that supposedly provides sun protection but resembles war paint, giving Yangon the look of a city constantly prepared for a medieval battle.

From the 11th to the 13th centuries, devout Burmese monarchs built at least 4,000 temples in Bagan, across more than 32 square meters in central Myanmar's wide plains. Roughly 644km north of Yangon stands this monument to Burmese civilization, one of the most impressive architectural achievements in Asia. Though some original temples no longer exist, there are still thousands on the plains, from slim cathedral-like buildings to stocky, square monuments. Some reach 55m high, with elaborate terraces, porticos and bas-reliefs.

In contrast to other monuments like Angkor Wat in Cambodia, Bagan still receives so few tourists that you can hike among ruins for hours without seeing another person. At dusk, I can sit at one of the temples, undisturbed as I watch perhaps the most spectacular sunset in Asia, the sun bathing the temples in purple and crimson, creating silhouettes of the ancient stupas, and finally setting over lush fields.

By the time the British took over the country in the late 1800s, the center of Burmese royal attention had moved north to Mandalay, along the chocolaty Ayeyarwady River. As capital of Myanmar, Mandalay too became a center for Buddhist scholarship.

Today Mandalay, close to neighboring China, has also become a vibrant economic and cultural center. In the older part of town, I walk into homes where women still weave kalaga, the hand-embroidered tapestries traditionally used to decorate royal palaces. In the newer section of town, a friend and I wander through a glass-and-steel shopping mall dominated by Chinese electronics and fashions, where Burmese salesgirls peddle short dresses. When my friend asks one salesgirl whether it's acceptable in Myanmar's conservative culture for her to wear thigh-high boots and spike heels, she replies that it's not a problem -- even as elderly women in long frocks and traditional turbans stare into the store, seemingly mesmerized.

As everywhere in Myanmar, tourists in Mandalay cannot avoid encountering the government. Outside the colonial-era Mandalay Fort, an austere walled city around a shimmering moat reportedly rebuilt with forced labor, signs vow that the army will "crush" all enemies, and troops stop cars at will. Gangs of workers dig ditches along the airport road, and several travelers I spoke with saw what they believed to be forced labor in this region.

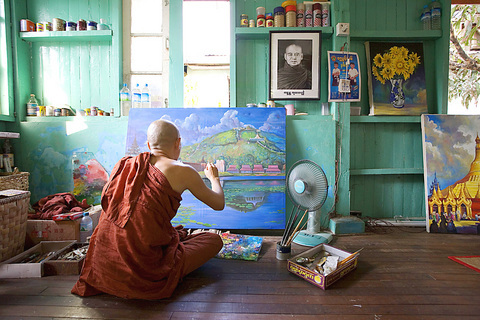

Local tour guides can be frank in their critiques; mine pointed out checkpoints where the police and soldiers constantly asked for bribes, before adding, "I can only talk like this alone, in the car" and asking me never to reveal his name. In Mandalay's theater area, home to Myanmar's companies that put on pwes -- a kind of vaudeville where actors perform into the early morning -- this dissent often plays out through art. Traditionally, pwes centered on broad jokes and interpretations of classical theater, though they also could be used to send subtle political messages, as performers could joke about topics commoners would never tell the king. Under military rule some performers once again use pwes and music for a kind of back talk to authority; in Yangon, Burmese gangsta rap has become a vehicle for mild dissent.

My last evening in Mandalay, I visit a decrepit dirt street to see Myanmar's most famous vaudevillians, who have paid a steep price for their laughs. In an open front room that doubles as a makeshift stage, the Moustache Brothers perform every evening.

Two of the three Brothers were arrested a decade ago for telling jokes critical of the government, and served nearly six years in prison. (Western comedians pressed for their release, and Hugh Grant mentioned them in the movie About a Boy.) Today, the regime allows them to perform only for tourists, and for US$3 a person they stage a bizarre mix of snippets from gorgeous classical Burmese dance, topical political humor, playful banter and attempts to frighten the audience. Indeed, the six people in the crowd around me seem alarmed when Lu Maw, a wiry Brother who mixes stories of government corruption with odes to Jennifer Lopez's booty, jokes that he's running out the back door because the police are coming.

Some of their comedy feels more like tragedy -- at one point, Lu Maw asks me to steal toiletries for him from my hotel -- but the Brothers never waver in poking fun at their rulers. As the evening draws to a close, they invite the audience to pose for photos with them, holding signs warning that the guests will now be under surveillance in Myanmar. "Show this to the police and see what happens," Lu Maw dares me, handing over his business card.

For the time being, and under this government, average Burmese like Lu Maw can only rely on the traditions that have sustained them so long.

STRATEGIES FOR SPENDING JUDICIOUSLY

Before planning a trip, you might want to read up on the country and its political situation so you can make an informed decision on whether to go. The Lonely Planet is the best English-language travel guide to Myanmar, and the Irrawaddy magazine (www.irrawaddy.org), published in Thailand, covers Burmese news online.

Fly to Bangkok or Singapore and continue on from there. From Bangkok, Thai Airways (www.thaiairways.com) flies to Yangon; in late April, a mid-May round trip was US$266. From Singapore, Silk Air (www.silkair.com), the regional wing of Singapore Airlines, flies to Yangon; in late April, a mid-May round trip was US$440. Get paper tickets for your flight to and from Myanmar, as the country's airport system is antiquated; e-tickets will prove useless.

Once in Myanmar, stick to Air Mandalay (www.airmandalay.com) if you can for your domestic flights as it has a better safety record than other domestic carriers.

If you want to give as little money as possible to the Myanmar government, you can adopt several strategies. Avoid taking package tours, and make local transport and accommodations arrangements with an independent Burmese travel agent, who will most likely know how to avoid many government-owned shops and other attractions. Travelers' recommendations of local travel agents can be found on Lonely Planet's Thorn Tree Web site, www.thorntree.lonelyplanet.com. I found an excellent agent and guide there.

Three big changes have transformed the landscape of Taiwan’s local patronage factions: Increasing Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) involvement, rising new factions and the Chinese Nationalist Party’s (KMT) significantly weakened control. GREEN FACTIONS It is said that “south of the Zhuoshui River (濁水溪), there is no blue-green divide,” meaning that from Yunlin County south there is no difference between KMT and DPP politicians. This is not always true, but there is more than a grain of truth to it. Traditionally, DPP factions are viewed as national entities, with their primary function to secure plum positions in the party and government. This is not unusual

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

More than 75 years after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Orwellian phrase “Big Brother is watching you” has become so familiar to most of the Taiwanese public that even those who haven’t read the novel recognize it. That phrase has now been given a new look by amateur translator Tsiu Ing-sing (周盈成), who recently completed the first full Taiwanese translation of George Orwell’s dystopian classic. Tsiu — who completed the nearly 160,000-word project in his spare time over four years — said his goal was to “prove it possible” that foreign literature could be rendered in Taiwanese. The translation is part of