After 42 years of military service, Retired Brigadier General Ezell Ware Jr. ("Call me EZ") mobilized to Austin last year. "It's not like I just threw a dart," he says with a wide grin. He left California and ended up here after carefully evaluating his "courses of action."

Not willing to retire into a golfing community, he plotted on a graph the average age, median income, level of education, tech savvy, political bearing and, of course, country and western music heritage of a dozen cities.

Ware soon narrowed his choices to Austin, and now he lives in a strategically located apartment on the crest of a ridge high over Capital of Texas Highway. The apartment is spartan. "It's important to me to wake up each day a clean person," he explains.

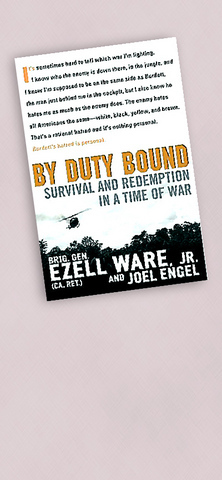

The place doesn't feel lived in because it hasn't been. Ware landed in Austin last summer, and has been busily promoting his gripping memoir, By Duty Bound, a cinematic piece of work that flashes back and forth between a harrowing tale of survival in Vietnam and his upbringing as a black man in the Jim Crow South. A helicopter pilot during the war, Ware struggles to help his co-pilot to safety after the two are shot down in the jungle. The fight for survival -- and the revelation that his co-pilot was a Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragon -- prompt the recollections of his hardscrabble life in Mississippi.

Winter mornings he might wake with frost in his hair. Laundry was a two-day chore with "clothes that hadn't been new when they were new." Pa, his grandfather and a sharecropper, looked "as beaten as the hollow black men I'd seen all over Magee -- human pinatas who'd had their dreams and laughter knocked out of them."

Coming of age, black, in 1950s Mississippi prepared Ware for the Vietnam War.

"There are wars and then there are wars, and within every war there are wars within wars," By Duty Bound begins. "In Vietnam, it's sometimes hard to tell which war I'm fighting. I know who the enemy is down there, in the jungle, and I know I'm supposed to be on the same side as Burdett, the man just behind me in the cockpit, but I also know he hates me as much as Charlie does. Probably more. Charlie doesn't really hate me; he just wants me dead so I can't kill him. But if he does hate me, it's because I'm an American, and Charlie hates all Americans the same -- white, black, yellow, and brown. That's a rational hatred -- a hatred for your wartime enemy, and it's nothing personal -- Burdett's hatred is personal."

Now, far from the jungles of Vietnam, Ware has just returned from a trip to Paris and Amsterdam where he was working out a translation deal for his book. The day we speak, he's heading off for a trip to California, where he lived for 15 years, leading the state's National Guard.

After a long, successful military career he has no brigade to lead, and his life seems to be consumed with his second career as an author and a steady course of self-improvement. Besides a dozen copies of By Duty Bound, he owns an Idiot's Guide to Creative Writing, Spanish for Dummies and Guitar for Dummies. He is taking a "mega memory" course in Spanish and learning to "photo read."

He also works, perhaps unsurprisingly, as a motivational speaker (several times, he says that he "values the joys in life"). "I'm busy," he says. "You wake up every day running, like a lion or a gazelle." But the unquenchable self-improvement, the occupation of it all, seems driven by a certain solitude. "I don't know anyone in Austin," admits the divorcee. His grandmother passed away in 1962; he didn't return to Mississippi to visit her grave until 2000. "I couldn't name 25 people I served with in 42 years," he says.

In fact, it's the closeness of the war -- the thousand ways in the messy heat that he got to know his fellow soldiers -- that appears to have, paradoxically, left him so isolated. In one episode in By Duty Bound, a South Vietnamese man snatches Ware's camera. "Hey!" Ware shouts, and for an instant there is a bond, even if it is that between a thief and his victim. The next moment the man, who has evidently stepped on a land mine, "was just pieces of body flying through the air like debris in a storm ... I did not see my camera land," Ware writes.

"People came in and went out of your life so fast, you had to think of them as interchangeable, unless you knew they were going to play a role in your own story," he explains in By Duty Bound. "Names, faces, skin colors -- they were all the same. ... The irony was that the closer you got to death, the closer you got to the people who were with you. Danger would become an invisible hand that brought you unnaturally close unnaturally fast."

Deep in the Vietnam jungle he found himself closest to the man least like him, his blubbery, self-pitying, West Virginian co-pilot, a Klansman whom Ware only calls Burdett. His leg badly wounded in the helicopter crash, Burdett must rely on Ware to bear him to safety. And it is high in a banyan tree, after a meal of raw crickets, that Burdett makes his confession. Ware seems to care little (or maybe he is just unsurprised) about the admission. He just wants to be evacuated.

He is now, and was then, matter-of-fact. And his blackness, then, and now, was simply a fact, not a defining feature. "I did not want to put a glass ceiling on myself."

For a man raised in the Deep South in the 1940s and 1950s, the relatively color-blind military offered a world in which he could lift himself up by his boostraps. "Still hanging on a wall in my memory is a Life photograph of a Marine returning from the South Pacific after World War II," he writes in a recollection of his early childhood. "He'd obviously seen and done things that I wanted to see and do. For some reason, I ached to be that Marine. That he was white and I was black wasn't a thought that occurred to me, not even in passing. Such a thing didn't seem to matter. As far as I was concerned, we were both Americans, and that gave us more in common than we had differences."

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she