Mao Xinyu (

"In this new century, this new period of history, to publicize Mao Zedong's (

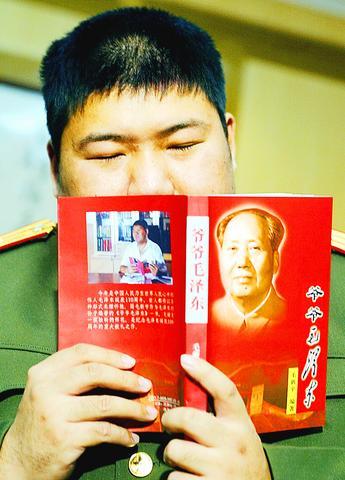

PHOTO: REUTERS

More than a quarter-century after his death in 1976, Mao's continuing status as a global pop icon contrasts with the increasingly acknowledged bankruptcy of his politics, a pretext for all kinds of irony.

The burden of reconciling China's past and present has been thrust on the distended frame of his grandson, who is said to have grown up sheltered by servants and guards, kidding classmates about what he'd do when he took power.

In a generation of "little emperors," he appeared to fit the mould better than any, logging mediocre test scores and tipping the scales at more than 114kg.

Today, as an army-trained Mao historian and lieutenant-colonel, Xinyu, 33, remains a ceremonial figure. But while he has slimmed little, he has matured a good deal.

Sitting back in a voluminous green uniform, swearing to uphold Mao's guerrilla gospel, he faintly resembles his grandfather -- part country bumpkin, part quixotic bookworm, part sprawled-out sovereign.

"Aya, there's pressure, there's pressure," he sighed, with a puffy-cheeked grin, at the end of an interview. "Because the whole nation's people have their eyes on me."

Moments after Xinyu left, one of his publicity aides at the Academy of Military Sciences explained that "pressure" was meant to convey filial respect, all the more so for an ancestor of his grandfather's stature.

Mao's 110th birthday, Dec. 26, came and went last month, making no great waves in Chinese public life.

The Communist Party aired the usual television hagiographies while capitalistic co-sponsors peddled the latest gimmicks, from books spinning Mao's wartime survival tactics into management tips to hip-hop music recordings of his trademark theories.

Xinyu, for his part, did a rare run of interviews and book signings to promote his new anecdotal history, Grandpa Mao Zedong.

The paperback has sold several tens of thousands of copies, the Ph.D. replied modestly when asked. Later he suggested, "I'll give you the rights. You can translate it!"

The Great Helmsman named him Xinyu, or "new universe."

His father, Mao Anqing, the chairman's second son, was a party interpreter before succumbing to schizophrenia; his mother Shao Hua, an esteemed photojournalist, is a major-general. His wife is also in the army.

In China's elite circles today, many so-called princelings milk their pedigree to find jobs in prize industries, from real estate (party boss Hu Jintao's (胡錦濤) daughter) to semi-conductors (military chief Jiang Zemin's (江澤民) son). Some hold official posts themselves.

For Mao's heirs, the chambers of party power were seemingly off limits, the boardrooms of business sure to incur scandal.

So the family -- said to suffer from bad genes and be subject to bad grudges by elites rehabilitated after the Chairman's 1966 to 1976 Cultural Revolution -- came to depend on the military.

Xinyu insists his clan simply have their own special calling, to act as "successors" to Mao's revolutionary work.

"As the Chairman's relatives, we must take heed to serve the people at every turn," he said.

As for those counter-revolutionaries who exploit Mao's image for personal gain, with kitsch cigarette lighters and so on, he has a rosy-red outlook. "If you ask to me look at these phenomena and what they relate to, I believe China's common people want to have beliefs and spiritual sustenance."

"Since the 100th anniversary especially, I feel that common Chinese people's spiritual beliefs and spiritual sustenance have been embodied in Chairman Mao."

That was less than apparent in the capital on Mao's 110th birthday. While many stopped to snap souvenir photos before the Tiananmen rostrum, where Mao proclaimed the People's Republic in 1949 and where his portrait still keeps watch, perhaps as many lined up outside department stores for shots with Santa Claus.

Xinyu said that one reason he wrote his book was to dispel certain Mao "myths," although he declined to cite examples.

The authorities have banned some books over the years, such as physician Li Zhisui's notorious portrayal of Mao as a randy megalomaniac.

As with many Chinese biographies of the late Chairman, 90 percent of Xinyu's volume focuses on the pre-1949 Mao, credited with emancipating the masses after millennia of feudalism. The Mao blamed for 30 to 50 million deaths from famine during the Great Leap Forward and millions more in the Cultural Revolution goes unmentioned.

But even this self-styled Mao disciple bows to the accepted verdict in China: Mao made mistakes, but his contributions exceeded them.

In the March 9 edition of the Taipei Times a piece by Ninon Godefroy ran with the headine “The quiet, gentle rhythm of Taiwan.” It started with the line “Taiwan is a small, humble place. There is no Eiffel Tower, no pyramids — no singular attraction that draws the world’s attention.” I laughed out loud at that. This was out of no disrespect for the author or the piece, which made some interesting analogies and good points about how both Din Tai Fung’s and Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co’s (TSMC, 台積電) meticulous attention to detail and quality are not quite up to

April 21 to April 27 Hsieh Er’s (謝娥) political fortunes were rising fast after she got out of jail and joined the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) in December 1945. Not only did she hold key positions in various committees, she was elected the only woman on the Taipei City Council and headed to Nanjing in 1946 as the sole Taiwanese female representative to the National Constituent Assembly. With the support of first lady Soong May-ling (宋美齡), she started the Taipei Women’s Association and Taiwan Provincial Women’s Association, where she

It is one of the more remarkable facts of Taiwan history that it was never occupied or claimed by any of the numerous kingdoms of southern China — Han or otherwise — that lay just across the water from it. None of their brilliant ministers ever discovered that Taiwan was a “core interest” of the state whose annexation was “inevitable.” As Paul Kua notes in an excellent monograph laying out how the Portuguese gave Taiwan the name “Formosa,” the first Europeans to express an interest in occupying Taiwan were the Spanish. Tonio Andrade in his seminal work, How Taiwan Became Chinese,

Mongolian influencer Anudari Daarya looks effortlessly glamorous and carefree in her social media posts — but the classically trained pianist’s road to acceptance as a transgender artist has been anything but easy. She is one of a growing number of Mongolian LGBTQ youth challenging stereotypes and fighting for acceptance through media representation in the socially conservative country. LGBTQ Mongolians often hide their identities from their employers and colleagues for fear of discrimination, with a survey by the non-profit LGBT Centre Mongolia showing that only 20 percent of people felt comfortable coming out at work. Daarya, 25, said she has faced discrimination since she