Roman Polanski's new movie, The Pianist, is based on the memoirs of Wladyslaw Szpilman, a star of Polish radio and cafe society in the 1930s and a member of Warsaw's assimilated Jewish middle class, who lived through the Nazi occupation and the Warsaw ghetto. Szpilman's recollections, published shortly after the war, offer, like other such books, a deeply paradoxical impression of the Holocaust. Accounts of survival, that is, are both representative and anomalous; they at once record this all but unimaginable historical catastrophe and, without intentional mendacity or inaccuracy, distort it.

The reason for this could not be simpler. Most of the intended victims of Nazi genocide did not survive; the typical Jewish experience in 1940s Europe was death. One of the main genres that allow later generations access to this time thus presents an inevitably unrepresentative picture of it.

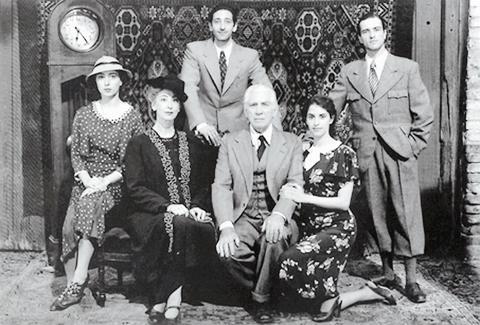

PHOTTO COURTESY OF UNIVERSAL

We naturally identify with the protagonists of these books, and the characters based on them in movies and plays, and so imagine that we would have been among the lucky ones, even if the real odds suggest otherwise. (We also comfort ourselves in the vain belief that, had we been there, we would have bravely defied the Nazis, risking our own well-being to help their victims.) When it is not treated with the uneasy sentimentality reserved for miracles, survival -- whether through dumb luck, resilience, the kindness of strangers or some combination of these -- is often viewed with a deep and bitter sense of the absurd.

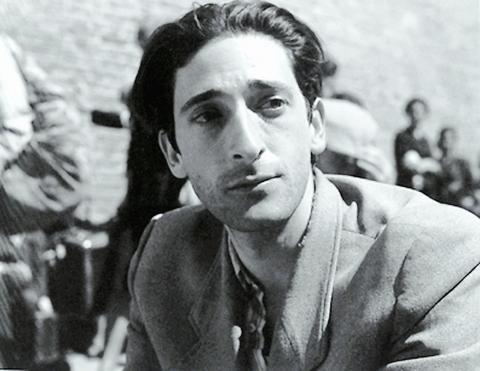

PHOTTO COURTESY OF UNIVERSAL

Polanski, who was a Jewish child in Krakow when the Germans arrived in September 1939, presents Szpilman's story with bleak, acid humor and with a ruthless objectivity that encompasses both cynicism and compassion. When death is at once so systematically and so capriciously dispensed, survival becomes a kind of joke. By the end of the film, Szpilman, brilliantly played by Adrien Brody, comes to resemble one of Samuel Beckett's gaunt existential clowns, shambling through a barren, bombed-out landscape clutching a jar of pickles. He is like the walking punchline to a cosmic jest of unfathomable cruelty.

Perhaps because of his own experiences, Polanski approaches this material with a calm, fierce authority. This is certainly the best work Polanski has done in many years (which, unfortunately, is not saying a lot), and it is also one of the very few nondocumentary movies about Jewish life and death under the Nazis that can be called definitive (which is saying a lot). And -- again paradoxically -- this is achieved by realizing the modest, deliberate intention to tell a single person's story, to recreate a specific and finite set of events. (Ronald Harwood's script does take some necessary liberties with Szpilman's account, but these seem justified by the demands of movie storytelling.)

PHOTTO COURTESY OF UNIVERSAL

The ambition to produce a comprehensive vision, a single spectacle adequate to the Holocaust ultimately defeated Steven Spielberg's admirable and serious Schindler's List. Polanski, in staging a narrow, partial slice of history, has made a film that is both drier and more resonant than Spielberg's.

One of Polanski's trademarks is what might be called (to continue multiplying paradoxes) a humane sadism. He has always been fascinated by what happens to weak, ordinary people -- Mia Farrow in Rosemary's Baby, for instance, or Jack Nicholson in Chinatown -- when they are intruded upon by evil forces more powerful than they, and he punishes his actors, peeling back their vanity to make them show the face of humanity under duress.

One of Brody's most appealing features from King of the Hill 10 years ago through such varied and underseen pictures as Restaurant, Summer of Sam and Bread and Roses more recently, is his quick-witted, almost smart-alecky cockiness. His Szpilman, in the first section of The Pianist, has the gait of a self-satisfied dandy and the smug smile of a man who takes charm and good fortune as his birthright.

As he plays piano in a broadcast studio, an explosion rattles the building. He ducks, wipes some plaster off his sleeve, and keeps playing. Later Szpilman refuses to allow the widespread panic at the German invasion to interfere with more pressing matters, like the seduction of a star-struck young woman named Dorota (Emilia Fox).

History, the occupying Germans and Polanski then conspire to wipe the smirk off his face. The Nazi takeover is followed by a swift, brutal chronicle of violation and humiliation as the Szpilman family are stripped of their possessions, their dignity (the elderly father, played by Frank Finlay, is beaten by a German soldier for daring to use the sidewalk) and their home. With the other Jews of Warsaw, they are herded into the ghetto, a captive labor force subject to continual culling by disease, starvation and random violence.

Polanski, working in Poland for the first time in 40 years (and also in Prague), reconstructs the look and rhythm of life in the ghetto with care and sobriety. You feel the dread and confusion of the inhabitants and you also observe their intuitive, futile attempts to master the situation, circulating underground newspapers, smuggling contraband through the walls and quietly arming themselves.

The survival instinct is shown to exist in a weird, numb state that combines defiance and resignation. And Szpilman's evasion of death involves a curious combination of pluck, passivity and arrogance. He is the only member of his family who avoids being shipped to the extermination camps and he later manages to escape from the ghetto altogether. During the 1943 ghetto uprising, he is locked in a secure apartment in the gentile part of the city, and he watches helplessly from the window as the partisans begin their brave, doomed resistance to the German occupiers.

From this moment forward The Pianist becomes a tour de force of claustrophobia and surreal desperation and Polanski ruthlessly strips his Szpilman down to the bare human minimum. He is neither an especially heroic nor an entirely sympathetic fellow, and by the end he has been reduced to a nearly animal condition, sick, haggard and terrified. But then the film's climax offers the most dramatic paradox of all: a glimpse of how the impulses of civilization survive in the midst of unparalleled barbarism.

When I first saw this film last spring in Cannes (where it won the Golden Palm), I thought Szpilman's encounter, in the war's last days, with a music-loving Nazi officer courted sentimentality by associating the love of art with moral decency, an equation the Nazis themselves, steeped in Beethoven and Wagner, definitively refuted. But on a second viewing, the scene, scored to the ravishing, sorrowful music of Chopin, was a painful and ridiculous testament to just how bizarre the European catastrophe of the last century was.

Szpilman may have been the butt of a monstrous joke, but the last laugh appropriately deadpan, was his. "What will you do when this is over?" the officer asks. "I'll play piano on Polish radio," Szpilman replies. Which is exactly what he did until his death two years ago.

From an anonymous office in a New Delhi mall, matrimonial detective Bhavna Paliwal runs the rule over prospective husbands and wives — a booming industry in India, where younger generations are increasingly choosing love matches over arranged marriage. The tradition of partners being carefully selected by the two families remains hugely popular, but in a country where social customs are changing rapidly, more and more couples are making their own matches. So for some families, the first step when young lovers want to get married is not to call a priest or party planner but a sleuth like Paliwal with high-tech spy

With raging waters moving as fast as 3 meters per second, it’s said that the Roaring Gate Channel (吼門水道) evokes the sound of a thousand troop-bound horses galloping. Situated between Penghu’s Xiyu (西嶼) and Baisha (白沙) islands, early inhabitants ranked the channel as the second most perilous waterway in the archipelago; the top was the seas around the shoals to the far north. The Roaring Gate also concealed sunken reefs, and was especially nasty when the northeasterly winds blew during the autumn and winter months. Ships heading to the archipelago’s main settlement of Magong (馬公) had to go around the west side

Several recent articles have explored historical invasions of Taiwan, both real and planned, in order to examine what problems the People’s Republic of China (PRC) would encounter if it invaded. The military and geographic obstacles remain formidable. Taiwan, though, is part of a larger package of issues created by the broad front of PRC expansion. That package also includes the Japanese islands of Okinawa and the Senkaku Islands, known in Taiwan as the Diaoyutai Islands (釣魚台), to the north, with the South China Sea and certain islands in the northern Philippines to the south. THE DEBATE Previous invasions of Taiwan make good objects

Some people will never forget their first meeting with Hans Breuer, because it occurred late at night on a remote mountain road, when they noticed — to quote one of them — a large German man, “down in a concrete ditch, kicking up leaves and glancing around with a curious intensity.” This writer’s first contact with the Dusseldorf native was entirely conventional, yet it led to a friendly correspondence that lasted until Breuer’s death in Taipei on Dec. 10. I’d been told he’d be an excellent person to talk to for an article I was putting together, so I telephoned him,