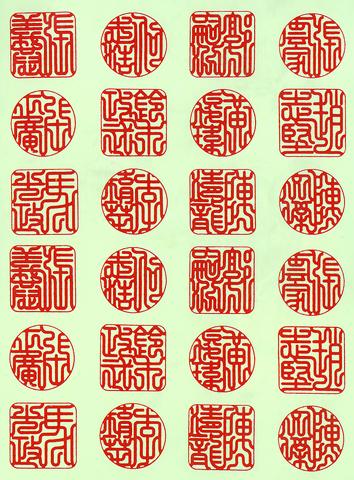

You can have them cut for NT$50 at street-corner stalls or get them elegantly carved in jade or other semi-precious stones. Seals are still an integral part of Taiwanese life, but their significance is gradually changing as signatures gradually replace the seal as a means of confirming a transaction.

For Lonmen Lucky Stamp (

In a time of economic downturn, those who take seals seriously are primarily interested in their ability to bring good fortune. And this isn't something for uneducated country bumpkins either.

PHOTO: VICO LEE, TAIPEI TIMES

The majority of its customers are not, as you might expect, tradition-minded country folk, but urban business people and government officials of various ranks.

"It seems that the more educated and better-off people are, the more they care about their fortunes," said Chen Tian-zang (

PHOTO COURTESY OF LONMEN LUCKY STAMP

And in these times of economic gloom, people care more than ever. Despite the prevalent cries of poverty, Lonmen has no difficulty in disposing of a pair of rectangular and cylindrical jade seals for NT$36,000. At Lonmen, even the most common type of lucky seals are priced between NT$1,500 and NT$5,000 a piece.

While the average seal maker cuts maybe a couple of seals a day, Yang Feng-yin (

Lonmen started 10 years ago in Taichung, working only through mail order. It has now fanned out into 20 branches in shopping malls in Taiwan's major cities. Five to 10 more branches are scheduled to open in Taipei alone.

It all started with a promotional activity at Taichung's Far East Department store six years ago, when Lonmen staff -- all trained in the art of fortune-telling -- were asked to provide astrology sessions as prizes for shoppers. Over the ten-day promotion, Lonmen grossed more than a NT$1 million. From then on, Chen decided that setting up in swank department stores and malls was the way to go.

"Big malls are the place to be. Individual workshops are going downhill. Malls are where crowds gather and where we can reach out to the largest possible public," Chen said.

The seal company's success story has attracted the attention of both the Chinese media and business analysts, who wonder how Lonmen had managed to bring in over NT$100 million a year in revenues from what is perceived as a very unfashionable industry.

Other peolpe's luck

It all has to do with luck -- other people's luck. Yang, the creative spirit behind the enterprise, started thinking about "lucky seals" as an alternative to "aesthetic seals" back in the 1980s.

"It's hard to achieve the artistic mastery of our ancestors. In ancient days, a craftsman did nothing but carve seals all his life, but nowadays we have too many distractions," said Yang.

He felt that lucky seals would have a much bigger market. "Artistic seals are hard to sell. Few people know how to appreciate them nowadays. But everyone needs good luck. They all have some use for seals which can bring good luck."

The encounter between Chen and Yang 10 years ago changed both their lives. Then a real estate dealer, Chen had Yang make a lucky seal for him. Yang's theory about the close connection between a seal and the fate of its master touched Chen so deeply that he decided to join in a project, broached by Yang and his friend Tzai Ruei-min (蔡瑞銘, present chairman of the company board), to establish a seal-making company.

Drawing inspiration from his former job, Chen said, "People pay great attention to the house they live in. They care about all aspects of the building when house-hunting -- the materials used, its convenience, structure and fengshui. The same level of care should be taken over the house their name lives in -- their personal seal. As everyone has a name and needs a seal, the market is unlimited," Chen said.

Chen, who owns eight pairs of seals, is a believer in the power of a piece of jade with his name on it. "There's an ancient saying: `first, fate; second, luck; third, feng-shui; fourth, good deeds; fifth, effort.' There's no one single decisive factor for success. We have to work hard and at the same time look for things that can speed up our success," Chen said.

For a product that has so much to do with a customer's destiny, Chen decided that only people convinced of the seals' powers and versed in the I Ching -- also known as The Book of Changes and the final word in Chinese fortune-telling lore -- are qualified to sell them. Many of Lonmen's sales staff came into the job after discovering the efficacy of Yang's seals.

Chu Wen-ling (

She got herself a job as an accountant at Lonmen and had a pair of lucky seals made by Yang. "Talking with the salespeople was the first time I'd heard someone tell me I could change my own destiny. You know, Chinese tend to resign themselves to their destiny," said Chu, who later became confident of the power of lucky seals. "Maybe, it was also that I wanted to change. I wanted my life to be better. My confidence did its part."

Chu became one of Lonmen's saleswomen after two years as an accountant and shared her story with her customers.

Chen does not see the power of lucky seals as esoteric at all. "We are scientific people. We use the wisdom of our ancestors to make our lives better. It's different from superstition. It's only when you want your life to be better and you believe in it can the seals help you," Chen said.

Scientific theory

Chen's idea has something in common with the recent findings by British psychologist Richard Wiseman.

In an eight-year study, Wiseman found that the most common traits among lucky people is that they always expect themselves to be lucky and they grab the first chance to make the best of their luck.

Teaching people how to resist thoughts of fatalism and actively change their destiny is the main job for the over 50 instructors Lonmen has stationed in Taiwan's major cities for free consultations with its customers.

Equipped with at least a couple of years' training and assisted with computer fortune-telling software, these instructors see the problems of their customers from an astrological and psychological viewpoint.

"The four main topics of these consultations are business -- especially related to the current recession -- marriage, women having a bad time with their mothers-in-law and parents worrying over their kids," Chen said. As demand for psychological consultation rises, "fortune-psychology consultation," Chen said, is the way of the future.

Yu Rong-hsin (余榮信), a proprietor of a major chain of steak houses in the Taichung area, is a five-year customer of Lonmen. When Yu first bought a lucky seal, he was worried about his business in China. He asked advice on many aspects of his home and business life. "My investments have since paid off and my son, a nine-year-old, now plays the guitar quite well. I think the seals did help my family," Yu said "I think people always need something to rely on psychologically."

On the right side of fifty, Yang said he can handle the seal-cutting job on his own and has no need for apprentices until he knows there are "not many days remaining for me on Earth."

"Maybe in generations afterwards, seals will disappear from people's lives. I would like them to remember me as the man who pioneered [lucky seal enterprises]. Maybe they will give me some kind of title, something like `the great general of luck,' a title by which people call their prominent ancestors. Then I would have a place in the history of seals," Yang said.

President William Lai’s (賴清德) National Day address was the source of far more activity and response than the speech itself warranted. The reactions to the speech and subsequent events by the local press, the international press and the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) mouthpieces were all very different. Michael Turton’s excellent piece, “Lai lays out the future” in the Oct. 14 edition of this paper, provided some much-needed context and a critical examination of some crucial domestic issues Lai failed to address, adding the glorious comment: “the world parses Lai’s speech like Roman priests inspecting the guts of a sacrificial animal

Earlier this month Economic Affairs Minister Kuo Jyh-huei (郭智輝) proposed buying green power from the Philippines and shipping it to Taiwan, in remarks made during a legislative hearing. Because this is an eminently reasonable and useful proposal, it was immediately criticized by the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and Taiwan People’s Party (TPP). KMT Legislator Chang Chia-chun (張嘉郡) said that Taiwan pays NT$40 billion annually to fix cables, while TPP heavyweight Huang Kuo-chang (黃國昌) complained that Kuo wanted to draw public attention away from Taiwan’s renewable energy ratio. Considering the legal troubles currently inundating the TPP, one would think Huang would

Last week two magnificent exhibitions opened in London. Both have as their theme the idea of the Silk Road, an-overland trade route said to stretch ever since antiquity all the way across Asia from China to Turkey and hence to Mediterranean Europe. The show at the British Library is entitled A Silk Road Oasis: Life in Ancient Dunhuang and focuses on the extraordinary haul of ancient documents found in the Mogao Buddhist cave temples by a Chinese Daoist priest and sold by him to the explorer and archaeologist Aurel Stein in 1907. Its treasures include the celebrated ninth-century Diamond Sutra, the earliest

One of BaLiwakes’ best known songs, Penanwang (Puyuma King), contains Puyuma-language lyrics written in Japanese syllabaries, set to the tune of Stephen Foster’s Old Black Joe. Penned around 1964, the words praise the Qing Dynasty-era indigenous leader Paliday not for his heroic deeds, but his willingness to adopt higher-yield Han farming practices and build new roads connecting to the outside world. “BaLiwakes lived through several upheavals in regime, language and environment. It truly required the courage and wisdom of the Puyuma King in order to maintain his ties to his traditions while facing the future,” writes Tsai Pei-han (蔡佩含) in